|

|

|

garycohenrunning.com

garycohenrunning.com

be healthy • get more fit • race faster

| |

|

"All in a Day’s Run" is for competitive runners,

fitness enthusiasts and anyone who needs a "spark" to get healthier by increasing exercise and eating more nutritionally.

Click here for more info or to order

This is what the running elite has to say about "All in a Day's Run":

"Gary's experiences and thoughts are very entertaining, all levels of

runners can relate to them."

Brian Sell — 2008 U.S. Olympic Marathoner

"Each of Gary's essays is a short read with great information on training,

racing and nutrition."

Dave McGillivray — Boston Marathon Race Director

|

|

|

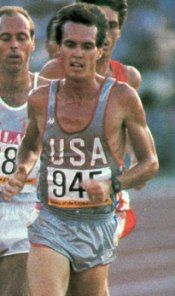

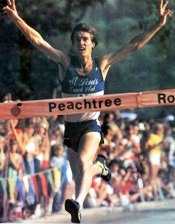

| Craig Virgin is the only American distance runner to win the IAAF World Cross Country Championships; which he did twice, in 1980 and 1981. On the roads he won the 1979 Falmouth Road Race in a course record 32:20, the 1980 and 1981 12 km Bay to Breakers race in San Francisco and the, 1979, 1980 and 1981 Peachtree Road Race 10k in Atlanta. He twice set American records for the road 10k in 1981 with a 28:06 2nd place at the Crescent City Classic in New Orleans and later a 28:04 win at Peachtree. . His fastest marathon in only four attempts was a 2nd place finish in the 1981 Boston Marathon in 2:10:26. Craig won three U.S. track 10,000 meter titles (1978, 1979, and 1982), was a three-time Olympian (1976, 1980 and 1984) and the winner of the 1980 Olympic Trials 10,000 meters. He was a nine time member of the U.S. squad at the World Cross Country Championships. While at the University of Illinois, Craig won nine Big Ten Conference championships and the 1975 NCAA Cross Country championship. He was the top American in eight NCAA national meets. He broke Steve Prefontaine’s American record 10,000 meters with a 27:39.4 in 1979 and lowered it to 27:29.16 in 1980 that was the second fastest 10,000 meters in history at the time. His personal best times include: 1,500m – 3:45.7 (1979); Mile – 4:02.8 (1976); 2 miles – 8:22.0 (1978); Steeplechase – 8:52.1 (1978); 5,000m – 13:19.1 (1980); 10,000m – 27:29.16 (1980) and Marathon – 2:10:26 (1981). Craig won five high school state championships (two in cross country and three in track) and set the national outdoor high school 2-mile record of 8:40.9. He competed despite having been born with a congenital urological disease which led to the 1994 removal of his right kidney. In 1997 he was involved in a head-on car collision where he almost died from his injuries. In 2001, Craig was inducted into the National Distance Running Hall of Fame. Currently he does freelance TV and radio commentary, personal coaching, and sports-themed motivational speaking for companies, running camps and schools. Craig grew up in Lebanon, Illinois where he currently resides and has one daughter, Annie. |

|

| GCR: | Let’s start where you stand alone in the history of American distance running as the only U.S. man to win the World Cross Country Championship with your two victories in 1980 and 1981. With the perspective of three decades, what does this accomplishment mean? |

| CV | It means the same thing now that it meant back then – for two days in my life I was the best in the world at something. And it’s not like American baseball, football or basketball – cross country is a world wide sport and in both of those years the world was very much involved. It was the culmination of three levels of cross country. At the high school level in Illinois, which is a very advanced and competitive state, I started at the bottom and worked my way to the top as a two-time state champion and still hold the state course record. I went to the Big Ten and won four titles in a row and am the only male to do that without a redshirt year in between. I won my only NCAA title in 1975. Then internationally I paid my dues in 1978 when I was sixth and in 1979 when I slipped in the mud and fell and worked my way up from outside the top 100 to a 13th place finish. In 1980 I set a goal of finishing in the top three and was able to do that and then some. |

|

| GCR: | One of your college rivals. 1983 Boston Marathon champion, Greg Meyer, said he believes your two world championships exceed Frank Shorter’s Olympic marathon gold medal and his Boston win. ‘In terms of pure athletic endeavor, the world cross country championship is a tougher accomplishment.’ You’ve competed in the Olympics and the Boston Marathon – what are your thoughts about this statement? |

| CV | I really respect Greg because he ran against me in college when he was at Michigan and he was one of only two Big Ten runners to beat me in cross country. Having to beat Greg Meyer and Herb Lindsay in college was tough as I could tell they were destined for greatness. Greg and I were roommates at my first World Cross Country Championship in 1978 at Glasgow, Scotland. In the World Championships you face the best in the world from the 1,500 meters up to the marathon. There were speedy 1,500 meter runners and strong marathon runners. I qualified for nine teams and ran eight. The world championships are a great athletic endeavor. Starting in the mid-1980s the Ethiopians and Kenyans turned it into a speed race. What Greg said I think is true as guys who were in the top ten in the WCs would go on to do great things on the track in July and August. It was a great compliment because of what Greg accomplished as a runner and our running against each other for four years in the Big Ten. Who’s to say who’s the best? Frank Shorter had gold and silver Olympic medals, but never won the Boston or New York City Marathon. Bill Rodgers won all of those Boston and New York marathons, but didn’t place well in the Olympics. Alberto Salazar won at Boston and New York, placed second and fourth at the World Cross Country Championships, but didn’t finish in the top ten in the Olympic Marathon in 1984. I did what I did in high school, college and afterward but never medaled in the Olympics. The point is, if you are considered ‘one of the best’ it is a great group to be in the company of and I am very proud. We all have had our outstanding moments, but no one has won them all. Some of those guys are my heroes and some I ran against. To be one of the top five or ten distance runners in U.S. history is a nice place to be. |

|

| GCR: | The 1980 Worlds didn’t start out smoothly as there was a false start and then a quick gun where many runners weren’t ready and you got tripped. What was your pre-race plan and how did you adjust after finding yourself way back in the field? |

| CV | I had won the U.S. trials, was captain of the team, got our runners organized in the box and there was a false start. I was reorganizing the guys with my back to the field and my own guys ran me over. I got untangled and found myself in 50th or 60th place and wanted to give up. But I had several ‘moments of truth’ that day when I made a conscious decision not to give up. In the first half mile I said to myself, ‘you’ve still got seven miles to go - a lot can happen – stay patient and try to work your way up.’ |

|

| GCR: | Since it was your third time at the Worlds, did your 1978 sixth place and 13th place in 1979 after falling early on a muddy course help you to stay calm and confident? |

| CV | In 1978 I got a good start and was in the top 15 the entire way. I didn’t know what I was doing but went off of my experience at the high school and collegiate level. In 1979 falling so far back and having to fight my way back past 100 runners showed me that I could move up if I just waited for openings and surged through them. |

|

| GCR: | During the five lap race you worked up to the back of the lead pack after three laps and were still 100 meters behind leader, Nick Rose. You closed to 20 meters back after four laps. Were you aiming for a medal or did a victory seem within reach at that point? |

| CV | With two laps to go when I finally caught the lead pack I looked ahead and saw Nick Rose about 100 yards out front running solo and no one was going after him. I had another ‘moment of truth’ decision and had to decide to either stay in the safety of the lead pack and hope they would run him down or to take off after Nick. We were rivals in college and I knew we couldn’t just give him the lead as I didn’t think he would die. I thought. ‘Did I come 3,000 miles to race for second or to try and win?’ I decided to slingshot around the lead pack and go after him. My goal was to be on Nick’s shoulder with a lap to go and to try to out sprint him on the last lap. I got closer and closer but on the home straight with a lap to go he looked back, saw me and took off. I looked over my shoulder and saw two runners coming up and thought I could be in trouble. But again I had a moment of truth when I had to answer the call. It tests our character, our resolve, our dedication and our desire to win at any price. Instead of giving up and saying, ‘I gave it the old college try,’ I had to make a decision once again to hang in there and let them push me as they were right behind me. |

|

| GCR: | You aren’t known as a kicker, but caught a fading Nick Rose with 150 meters to go and passed Hans-Jürgen Orthmann with only 70 meters left to win by one second. How did the race unfold physically and mentally on that last lap and during the final 400 meters? |

| CV | With about a kilometer to go I caught my second wind. Rose paid a price for making a big move at the bell lap. He was fading and we were closing. Orthmann took off with 600 or 700 yards to go. I had practiced the final stretch of the course several times during the two days before the meet and decided the straightaway was too long to start my kick so early. So I held back until under 400 meters to go and made first one move and then a second move with 150 meters to go and got by Rose. Then I nailed my last gear with about 100 meters to go and I got past Orthmann. That last 20 meters were the toughest 20 meters of my life. I could smell it but I was starting to run out of gas. I kept pumping my arms and the strength of my weekly hill intervals helped me to hold that drive through the finish. |

|

| GCR: | What was it like to win in Paris and to celebrate in Europe where cross country is so much more popular than in the United States? |

| CV | It was like winning the Indianapolis 500 or Kentucky Derby. The races were watched live on television across Europe. There was a betting line in the pubs. People would go to the pubs to watch the race as it was in the top tier of spectator athletic events on the continent. It wasn’t as big as the World Cup or Tour de France but just like with Lance Armstrong and Greg Lemond in the tour I had notoriety in Europe that I never fully capitalized on. I really needed to live there for a few months a year like the cyclists do. It would be easier now with the internet, cell phones, cable television and would be much more comfortable for an American to live in Europe for a few months than it was in the late 1970s and early 1980s. |

|

| GCR: | In 1981 you successfully defended your World Cross Country title in Madrid, Spain beating Ethiopia’s Mohamed Kedir by two seconds and Portugal’s Fernando Mamede by four seconds. How did that race unfold and did Kedir miscount the laps and push the pace one lap too early? |

| CV | The trials were in Louisville and I outkicked Nick Rose right at the end. Mark Nenow and Rose were out front. I passed Rose during the final two steps and knew I was ready for Madrid. Then the strange thing was that Rose was not selected by England to run on their WC team. I had a bit of a subpar day at those trials but still won, and subsequently ran a low 8:30s indoor 2-mile at the University of Illinois. When I arrived in Madrid, my sister, who was doing student teaching in Bath, England, came for the race. Unlike the prior two years, I started strong and was out with the top ten runners in the first kilometer. Kedir and Yifter had dominated the 1980 Olympics and were in Madrid along with Lopes and Mamede from Portugal. It was a loaded field. From one kilometer on I felt I was in control, biding my time. With two laps to go the Ethiopians started to sprint. I thought it was a surge and went with them. Coming into the home stretch with over a lap left I was in oxygen debt and knew I couldn’t sustain the pace for another two miles. I thought, ‘If you can hold this, you’re a better man than I am,’ and consciously let them go. Coming down the home stretch they veered right toward the finish and I realized they thought it was the last lap. Officials were waving them off and getting them back onto the course. They were confused so I knew it was time to make my move. The bell was clanging and I took advantage of their momentary confusion as they must have been in shock after sprinting for a one and a half mile lap, thinking they were finished and finding out they had a another lap to go. There were three or four Ethiopians in the front group. I was the only guy that had been with them as Mamede fell off before me. I had a enough presence of mind to make a move, but a half mile later I heard footsteps and Kedir had put the hammer down and caught me though I could tell he was breathing very hard and had paid a heavy price to do so. Unlike Lasse Viren did in the Olympic 10,000 meters when he got knocked down and slowly worked his way back to the pack to win the race and set a world record, Kedir had moved too quickly to catch back up with me. |

|

| GCR: | What tactics did you use in the final stages of the race that secured your second straight World Cross Country Championship? |

| CV | I didn’t let up but with 600 meters to go Kedir took off and went by me. I thought it was too early and with sports, business or love timing is everything. I let him go by and stayed close as I thought he had played his cards too early. With 400 meters to go I picked it up, caught him with 200 meters to go and found one more gear change. When you pass somebody you can’t just amble by, you’ve got to blow their doors off so you don’t just do physical damage but you do psychological damage as well. That is the art of passing people that young men and women need to know – you go ‘boom’ and put a few steps on them so that they get discouraged. I went by Kedir so fast and since he moved too soon he paid the price. In the last few meters the race photos do show that I was in agony. I had the thrill of pulling off a repeat after some people thought my victory was a fluke in 1980. I showed that I was a medal threat for the 1980 Olympic 10,000 meters. I don’t know if I would have beaten Yifter at Moscow for the gold medal - but I would have gotten gold, silver or bronze. I was at the epoch of my career. Any time of 58 or 60 or 62 seconds for the final 400 meters is fast at the end of a long cross country race on soft grass. I finished at 58 even back in high school so I had good speed – but nothing like Miruts Yifter who could finish with a 53 second burst for 400 meters and did so at the World Cup in 1979. I knew I had to have a faster pace and a broken pace with surges. Yifter’s finishing speed put him at an entirely different level at the end of a race so tactics had to be much different earlier. |

|

| GCR: | The United States placed second in the team competition both years with runners such as Thom Hunt, Dan Dillon, Mark Nenow, Bruce Bickford, Bill Donakowski, George Malley, Ken Martin, Steve Plasencia, Mark Anderson and Don Clary. Was there good camaraderie amongst you and your teammates and do you keep in contact with any of them? |

| CV | That is a big missing piece of the puzzle nowadays. Bill Rodgers was on the team in 1978 and mentored me. I will never forget what he did for me and I made it a point to do the same in the 1980s. There was a junior team competing at the World Championships with the senior team so the young runners learned a lot. Ed Eyestone wrote a column on ‘finishing kick’ and how hanging out with us in Paris made an impression on him as he finished third that year in the junior race. After 1978 I was resolved to strengthen our team and we had a nucleus of three or four guys who were on the team almost every year. As far as keeping in touch with my former teammates, I haven’t talked to Pat Porter now in a few years. I keep in contact sporadically with Bruce Bickford and Ed Eyestone. I see Steve Plasencia as he coaches at the University of Minnesota and I do some broadcasting for the Big Ten network. I talk to Bill Rodgers every now and then. Bill had a profound influence on me – in 1978 I was in my first year out of college and made the world championship team. In the three or four days in Glasgow, Bill gave me the ‘Cliff’s Notes’ version on the American road racing business. I will always treasure the help he gave me. Frank Shorter was polite and reserved, but I always got the feeling that he regarded me as competition. Marty Liquori was the dominant 5,000 meter guy in the late 1970s and very competitive. Bill Rodgers and Nick Rose were your buddies before and after the race but during the race it was cutthroat and every man for himself. |

|

| GCR: | How disappointing was it in 1982, when you were traveling to Rome in an attempt to win a third consecutive world cross country title and a kidney infection forced you to withdraw? |

| CV | I had made the team but wasn’t feeling well over the winter. I was en route to Rome but, as was my custom, first went to the adidas headquarters in Germany. I didn’t feel well, had a fever and got extremely ill. Amazingly, Thomas Wessinghage, a former great 1,500 meter and mile runner from West Germany, was a doctor and happened to be visiting at the Adidas offices three days after I got sick. He checked me out and got me right on the way to the hospital as my temperature was 106 degrees. One ureter had swollen shut and the kidney wasn’t draining. They were able to get the infection under control by piercing my back to drain the kidney externally, give intravenous antibiotics and save my life. It took me a week to get stable and I was able to get back to the states to a St. Louis hospital. I was so weak that I was just happy to get back to the United States in one piece and to have most of my kidney function return. |

|

| GCR: | What has changed regarding the United States lack of team competitiveness on the world cross country scene and what would you do to improve our team position? |

| CV | During the years I was a member of the U.S. team we had to give up three paydays – the weekend of the trials, the weekend before the Worlds and then the race weekend. The guys who ran the Jacksonville River Run couldn’t come back after the 15k and race well the next weekend. We made it a priority in our training and racing to try to win the worlds so that we could show the world what we had and our national pride. The difference now is that the trials and worlds are paydays. Back in my era we didn’t earn a cent except from shoe contract bonuses. We were there because of national pride and we wanted to win a world team championship. We were second about four times and third two or three times. I’m critical of our top runners now who go our trials, qualify for our team, collect the trials prize money and then skip the Worlds. They are too worried about a spring marathon, an important race or they don’t feel they can compete with the Africans. With the recent resurgence in American distance running I want to see our top six to eight men get on our team and take it to the Africans. We shouldn’t just concede to the Kenyan and Ethiopian teams. We have enough talent with a sub-27:00 10k runner, several low 27s and sub-13:00 5k runners and sub-2:10 marathoners. I think it all goes back to cross country and one of my goals is to help assemble the best team possible, take it to the WCs and kick some butt. One of the few goals I did not achieve was to bring back a men’s team championship. I would have given back one of my individual gold medals if we could have come back with a team championship. I am very proud of those teams that got second and third place. The U.S. cross country season is based mainly in the fall around the high school and college seasons and we were still able to kick some serious butt and do well. I would like to create an all-star American team and compete at a location that isn’t just chosen politically but is a great venue for cross country and to compete against the best in the world. I’d like to see what the best Americans can do if they commit to our country and they peak for a specific championship. |

|

| GCR: | You were a United States Olympian three times in the 10,000 meters in 1976, 1980 and 1984. What stands out from your first Olympic experience in Montreal? |

| CV | In 1976 I was a bit young as I didn’t turn 21 until midnight after the Closing Ceremonies. I had to run qualifying and finals in the 10,000 meters and qualifying, semis and a final in the 5,000 so racing over 21 miles was a lot to do. In 1976 the coaches talked me out of running the 5,000 meter final and saving myself for just the 10,000 meters as my calves were sore so I went out for an ‘easy’ 10-miler with Frank Shorter and Garry Bjorkland that we ended up doing in 49 minutes. I might as well have raced the 5,000 final. I was disappointed then in Montreal when I missed the 10,000 meter final and vowed to qualify in two events if I could in the future Olympic Trials to have a ‘fall back’ event. |

|

| GCR: | How disappointing was it to have your best chance for an Olympic medal taken away by President Carter’s 1980 boycott of the Moscow Olympics? How did the boycott affect U.S. track and field? |

| CV | We started hearing about a possible boycott in March of 1980 at the World X-C championships. One of the questions reporters asked the U.S. team was about the possibility of an Olympic boycott. I thought it was all political rhetoric that would go away. I thought that surely cooler heads would prevail. The main point of contention was that the Russians were in Afghanistan trying to put down an insurgency. The U.S. also was not happy with the Russian hardliners taking their stance against Poland and the Solidarity workers group. President Carter threatened many things but only followed through on two – the Olympic boycott and the grain embargo. The World Cross Country Championship race in Paris showed my fitness level and that year I went on to run 27:29 and 13:19 twice in ten days so it showed that I was in peak form for the Olympics. I trained from October to March to prepare for road racing and cross country as I thought it would get me ready for the Olympics. I sacrificed paydays on the indoor track circuit to put in a season like the Europeans. President Carter set back the Olympic competitiveness for eight years and triggered a 12-year agricultural recession in the U.S. with the decrease in corn prices right when interest rates went up and it killed the bank financed farmers. My prime racing years were from 1978 to 1981 so it hit me right at my peak with my best chance for an Olympic medal. I’d love to sit down with Jimmy Carter and do an interview of him on behalf of the other Olympians to find out what he was thinking at the time as all politicians have advisors and it’s often a consensus decision. I believe he had the best intentions but that his people didn’t understand the impact of the Olympic boycott and grain embargo and that in many respects it punished certain Americans more than the Soviet Union. I’d like to know why those were the only two items he didn’t waffle on as it would give former Olympians some closure. Nike did coordinate a reunion in 2008 at the Olympic trials in Eugene which helped somewhat and there were many people who were very emotional. We were back at the site of the trials and they gave each of us a video they put together of the trials and it was amazing to see the athletes competing as if they were still going to Moscow. They gave it their all even though they knew they weren’t going – they competed for pride and I admire them all. We were much better prepared in middle and long distance to compete for medals in 1980. Our strong team included James Robinson and Don Paige in the 800m, Steve Scott, Jim Spivey and Don Paige in the 1,500m, Dick Buerkle, Matt Centrowitz and Billy McChesney in the 5,000m and I was the fastest in the world for 10,000m as I set the American Record 10 days before the Olympics. We had a great distance team that did not get to compete. |

|

| GCR: | You were a seasoned veteran in 1984 for the Los Angeles Olympics, but didn’t some injuries prevent you from being at your best? |

| CV | In Los Angeles I turned 29 which back then was considered a real graybeard in track and field, though now this has changed due to the money in the sport. Now many athletes over age 30 make it to the Olympics. I wasn’t in the same condition as I was in for 1980. I had battled back from some injuries at the 1984 trials and may have trained a bit too hard between the trials and Olympics, I raced tactically but around four miles made a big move to shake things up. With three laps to go my left hip and back had some spasms and they caught up with me. I made the move I wanted to, but couldn’t hold it. It was a bitter experience for me as I was in a funk for a few days. I knew I wasn’t a medal contender but I wanted to make the finals. |

|

| GCR: | Did you attend the 1976 or 1984 Olympic Opening or Closing Ceremonies, watch other events at either Olympics or tour Montreal in 1976 as part of your Olympic experience? |

| CV | The Opening Ceremonies of both Olympics were the most special event to me as everybody had such high hopes and dreams of doing something wonderful. There was a feeling of anticipation sort of like on Christmas Eve. There was camaraderie in the village for a few days. The process was a long drawn out affair but there was no more moving moment in my life than coming into the stadium in Montreal with the music so loud, the bass thumping and a crowd with many Americans cheering so loudly. I wish I could have run my race then and there as my heart was thumping at about 180 beats per minute! The closing ceremonies were glad and sad at the same time – sad because the party was over and it is anticlimactic. The party wouldn’t assemble again for four years and no one there knew if they would be back. It was emotionally uplifting as the world came together in a peaceful way and all of the good things that the Olympics can be took place – it is magical how it brings people together. Back at the village everyone is partying and doing last minute trading of pins and clothing. People were out to swap and I was into training singlets, shorts and sweat suits. I had hoped to run into Nadia Comaneci in the village, but may not have recognized her in street clothes. A French Canadian liaison took us out on the town and it made my 21st birthday really special. I did not attend the 1984 Closing Ceremonies as my wife at the time was an Eastern Airlines flight attendant and we had to be at the airport at 6:00 a.m. I was bummed out and didn’t feel like celebrating but it is one of my biggest regrets ever that I didn’t take part in the closing ceremonies. I saw basketball and I tried to see two or three other sports although my first priority was my own sport. I sold and traded some of the tickets I was given to raise money for my family members to buy tickets to see my event as participants only received a limited amount. |

|

| GCR: | What are your thoughts on the American system of having to peak twice for the Olympic Trials and Olympics? |

| CV | It is hard to peak for the Olympics as you peak for the trials and then have to hold it for six weeks. If you can qualify with an 85% or 90% effort, then you can improve and peak for the Olympics. This is the challenge I learned in 1976. The Olympic Trials are like the Olympics as it is an emotional rollercoaster. The successful athletes keep an even keel, don’t get too high or too low, don’t do anything stupid and execute their plan. The USOC should send the top four to the Olympics and then if someone is injured, at least they would get the trip – that’s why so many athletes go injured and then they aren’t at their best. The qualifier who turns themselves in should get to go to the Olympics as a team member while the alternate performs. This would improve the overall American team performance. |

|

| GCR: | You were very successful at 10,000 meters on the track, winning three U.S. titles and setting the American Record twice with a 27:39.4 in 1979 to break Steve Prefontaine’s record and 27:29.16 in 1980. How did your mental approach differ on the track versus cross country and road racing? |

| CV | Track took much more intense concentration, especially when I started racing 12 to 25 laps – it wasn’t the most fun. After one lap of the 10,000 meters the sign says ’24 laps to go’ and you want to say, ‘wake me up with two laps to go.’ You have to use as little mental and physical energy as possible the first half of the race as the real racing never begins until the last 5,000 meters. The top three to six competitors will not drop until the final laps unless you run a very fast pace. In 1979 I had met all of my goals to that point and my next goal was to go after the American 10,000 meter record. I had done in the 27:50s and I decided to go for the record right from the gun. I couldn’t afford to go too easy as the commitment to go after Pre’s record was a self-imposed goal. I had left Athletics West and the coach and some of the athletes had taken some pot shots at me in the press. I had no one to train with and no coach in Lebanon, Illinois and people thought I was crazy. I went from the gun and set a torrid pace – Paul Geis went with me for a mile or two and then I was on my own. The word was out that I was going after Pre’s record and no one else wanted a piece of that. Every lap my college coach would give me a thumb’s up or down to let me know if I was on pace. It was one of my toughest races but let me know I was ready for bigger and better things. Cross country was a more relaxed race while in track it was so time oriented with splits every lap. The roads were like cross country on the streets. Road racing was good for me as I could use the hills and other parts of the course to my advantage to beat opponents. Also in 1979 after my discussions with Bill Rodgers I realized that there was more money to be made on the roads. I’d be lucky to get $500 to $1,500 for a track race whereas on the roads I could get at least $2,000 per race which eventually went up to $5,000. Many races brought me in because of my name and there weren’t a bunch of top level racers so I could train through them and still have a good payday. |

|

| GCR: | The roads were another venue where you piled up some impressive victories including Falmouth with a course record 32:20 in 1979 and three successive Peachtree 10ks culminating in an American Record 28:04 in 1981. Was your preparation and racing approach different on the roads? Are any of these races notable for their tactics or particular adversaries? |

| CV | In 1979 the Trevira Twosome 10-mile victory over Bill Rodgers was monumental as he hadn’t been beaten by an American in a race distance under a marathon in many years. At Peachtree I won by about 20 seconds and beat two-time winner Mike Roche. Falmouth had a strong field with Rodgers, Rojas, Meyer, Roche, Hodge and GBTC guys who were masters of road running. Ric Rojas took off and I ended being up the only one who caught him. I had to surge twice to break him and then worked to hold on. It was a huge thrill. The hot weather changed and then it started sprinkling. I had the bright idea to go back to the start where I was staying, shower, get changed and come back for the awards ceremony. We got caught in summer Cape Cod traffic and missed the entire awards ceremony. Their revenge curse was I that never won Falmouth again! I finished in different years in first, second, third, fourth and fifth. Peachtree in 1980 was strange as a participant died from heat exhaustion. As in 1979 I was in the lead up the hill midway, ran it strong and was unchallenged. In 1981 the Peachtree race organizers put together a tremendous field. Adrian Leek took it out and I was in third place going up the hill between three and four miles. I didn’t catch him until just past the 4-mile mark and Rod Dixon was trailing me by ten yards like a heat-seeking missile. He had beaten me before and had great mile speed. He tracked me but when I passed Adrian I surged hard and gained a bit on Dixon. When I entered Piedmont Park with less than a half mile to go Dixon was too close for comfort. I would surge every time there was a turn and he couldn’t see me, so I stretched the lead out to 30 yards. That was one of my highlights. The 1982 Maggie Valley Moonlight race was loaded with Michael Musyoki, Rod Dixon, Herb Lindsay, Rob de Castella and many others. They had television coverage since there was a baseball strike and the networks were looking for alternative sports to present to viewers. There was a pack of eight to ten guys and Herb took it out very fast on the downhill first half of the race. DeCastella tried to lose us and he broke, then Dixon broke and the last 400 meters was a duel with Musyoki. I didn’t beat him until the last three steps of the race. A finish line photo in the darkness shows us with wide open eyes and grimaces as we turned the 5-miler into a 50 yard sprint. It was the smallest race that had such a world class field. Top runners came for less appearance money because of the great hospitality and cool mountain weather. I raced well at San Francisco’s Bay-to-Breakers with two first place finishes and two seconds behind Rod Dixon. It is a tough race as there is a three-tier climb in the middle of the race before turning flat to downhill. The Crescent City Classic in New Orleans was memorable when Bill Rodgers and I raced hard and I won. The next year I broke the American Record in 28:06 which was significant even though I was beaten by Musyoki. They didn’t have high level 5k road races back in those days. They were ‘fun runs' and you only did them if you weren’t in shape. As far as the Gasparilla 15k and Jacksonville River Run 15k – they are great races but I was always training for the World X-C championships when the Florida races were held. |

|

| GCR: | Sometimes we hear of an athlete ‘being in the zone.’ Over a four-day span in 1979, you won the Penn Relays 10,000 meters with a sub-28:00, beat Bill Rodgers with a new American 10-mile record of 46:32.7 in Central Park and then flew to St. Louis, where you won the downtown Famous-Barr 10K. Were you in ‘the zone’ and was this part of perhaps a period of several years where you were at your peak and ‘in the zone?’ |

| CV | Yes I was ‘in the zone’ and at another level and was at that peak from 1978 to 1981. It’s like what Alberto Salazar did in 1981 and 1982 – he got into that zone and set American Records and PRs. Other top runners like Bruce Bickford and Doug Padilla went through a stretch like that. In 1980 I was feeling pretty good about myself after winning the World X-C and beating Bill Rodgers at Crescent City. At the Trevira Twosome Ten-Miler Herb Lindsay took off like a bat out of hell and got a lead of perhaps 80 yards. After halfway I realized he was really running strong and I went after him, tried to catch him and couldn’t. It told me that Herb, who was being coached by Frank Shorter at that time, was in that zone. My final track workout before the 1980 Olympic Trials was a mile, 880 and 440 in 4:06, 1:56 and 54. I knew I had to break the Olympic Trials record to beat Herb. I took the lead in the second lap and only Herb went with me. I knew I couldn’t go out slow and let someone sit on me like Yifter did in 1979. Herb was a Big Ten mile champ multiple times so I had to break away. We were around 13:46 or so at 5,000m which was only a few seconds slower than the third qualifying time for the 5,000m. Amazingly, we were this fast even though we were running at broken pace ‘fartlek’ style with many gear changes that I initiated. I broke him around 3.5 miles, he caught me at four miles and then as soon as he caught me I put in a surge for 400 – 500 meters and broke him again. He faded clear back to out of the top ten runners. I was so shot that I didn’t recover until a few laps to go and then pulled myself together and won in about 27:45. It was a pivotal race as it showed me that I had to have the ability to run a broken paced race with three or four surges of 400 meters in order to take the kick away from runners with more leg speed. |

|

| GCR: | You decided to experiment with the marathon in the late 1970s. Take us through the difficulties of adjusting to this new racing distance. |

| CV | My first marathon I ran 2:14:40 at the Mission Bay Marathon in San Diego which was a U.S. debut at the time and I felt more sore afterwards than after any previous race. It was terrible later that day, that night and the worst was the next morning when I got out of bed and tried to walk. I thought, ‘why are people so enamored with the marathon?’ My quads, hip flexors and everything was sore – it felt like someone had taken a baseball bat to my legs. All of these people are so hung up on marathons – but it takes a toll - you can’t go home and mow the lawn afterward. My next marathon race was Fukuoka in December of 1979 and I tried to get an Olympic Trials qualifier. Adidas didn’t get my custom shoes done in time so I did an old ‘track trick’ and stepped down from a size 9 ½ to a size 9 which gave me more arch support in a track event. I didn’t realize how much your feet swell in a marathon and two things happened. First, I was in the lead pack, got clipped from behind and went down so I was bruised, battered and scraped. But I did get back to the pack and was leading at the halfway point. Second, I started getting blisters and my feet got hot and sore. I could feel blisters everywhere and then I ended up with one massive blood blister on each foot. I ran 2:16:59 but they had to cut the shoes off of my feet as they were like hamburger meat. Ouch! |

|

| GCR: | Your limited marathon racing was highlighted by a second place behind Toshihiko Seko at the Boston Marathon in 1981 in 2:10:26. What was your strategy before the race, what adjustments did you make and what were the ‘crunch points’ that decided the outcome? |

| CV | I was in good shape after winning the World Championship X-C. However, my longest training run was an 18-miler and I was probably a bit undertrained for a tough marathon. I went out conservatively with the back of the lead pack. I had watched Rodgers break Seko in 1979 and had a similar race plan. I stayed with the lead pack at 12, 13, 14 through 16 miles and the dozen runners kept shrinking one by one. Finally there were only three of us left – Toshihiko Seko, Greg Meyer and me - and I tried to take Seko on Heartbreak Hill like Rodgers had. At the top I only had three strides on Seko and I knew that I was in deep trouble. After he was beaten two years earlier he came back and trained on the Boston hills with a samurai mentality that he wasn’t going to be beaten on the hills. I recovered at the top and we ran together until Cleveland Circle with 5k to go and he made a move that I could not respond to. I didn’t panic and stayed calm. For a mile I felt fine but in the last two miles I hit ‘the wall’ that I had always heard about. My pace slowed from under five minutes per mile to in the 5:20s. I felt like I was running in molasses. The crowd control wasn’t there and I felt claustrophobic with the tight crowds. I didn’t look back as I knew Bill Rodgers was coming strong and I didn’t want to give him any sign of weakness. Also, I knew there wasn’t a damn thing I could do! I just gutted it out and finished before he could catch me. I finished in a world of hurt. In fact I missed the entire post-race press conference as I was in the medical tent. |

|

| GCR: | Your fourth and final marathon was in Chicago in 1982 and didn’t you have some health issues that affected your racing ability on that day? |

| CV | I was coming off a decent late track and road racing season, there was a new era Chicago Marathon that was bringing in top runners and they hired me as a spokesman. Early in the week I felt symptoms of a urinary tract infection coming on but didn’t take antibiotics as they can make me sluggish - this turned out to be a mistake. I was running a quick pace early on, but knew by the two-mile point that I wasn’t strong. If I wasn’t the race spokesman I would have dropped out, but I felt a duty to keep going. I stayed with the back of the lead pack. Everyone was keying off of me and around 18 miles Greg Meyer and some other guys took off when they realized it wasn’t my day. The last eight miles were the longest eight miles of my life. But there were many young kids from schools that I had spoken to along the course cheering for me. I had told them that in the marathon you have to persevere even if things were getting really tough so I kept going. I didn’t want those kids to hear I had dropped out so I crawled in with a 2:17:29. You aren’t that uncomfortable in a marathon except for the last three to six miles if you train properly and you aren’t sick, but on that day it was just a struggle. |

|

| GCR: | What were some of the similarities and differences in your training when the focus was on the marathon rather than 5,000 meters and 10,000 meters? What were some of your favorite strength and building sessions? |

| CV | I never trained appropriately for a marathon – I just did an 18-mile run every 10 days. I trained like a 10,000 meter runner and cross country runner and added the 18-miler. The reason was I could run on a rails-to-trails pathway that was nine miles out and back and most of it was on cinders and dirt which made recovery easier. Looking back on it, when Seko made his move in Boston at 23 miles, the reason I didn’t have any gas was because I hadn’t done those 20 to 22 mile long runs. I wrote a dissertation with everything I’d learned from four years of high school, four years of college, my time at Athletics West and from talking with top runners in Europe and I put it all together into my training plan. I broke the year into four quarters. I rested in September which was a week completely off, a week of four miles a day, a week with two four-milers a day and then a week of four miles in the morning and six to eight miles later in the day. Oct – Dec was the first quarter which culminated in the holidays. The second quarter culminated in the World Championships X-C and the Crescent City Classic. The third quarter of Apr-Jun culminated with the US track championships and Peachtree. The fourth quarter was July, August, and Sept. The training was in the bag, so for two months I’d drop my mileage back, do intense track sessions and race. After August I’d rest again in September. In the fall I had a favorite four mile loop that I’d run each morning alternating clockwise and counter clockwise. My ‘bread-and–butter’ workouts were pretty simplistic. I did two hard sessions each week. The first was a 10-mile run with six hard miles of fartlek in the middle. There were two ways to do fartlek – by time or landmarks. I’d start with short bursts from one telephone pole to the next (maybe 100 yards), then some two telephone pole bursts and then I’d alternate between longer and shorter bursts. I didn’t like looking at my watch so I’d also use mailboxes or trees as landmarks. I didn’t go shorter than 200 yards or longer then three-quarters of a mile. I never let myself completely recover before I started the next surge. I was learning to battle oxygen debt. The other hard workout was 12 times a 400 meter hill – almost flat for 100, started to climb the second 100, worse the third 100 and semi-steep in the final 100. In the first quarter I concentrated on form and technique. Toward the middle I would do bounding up the hill with an accented knee lift, arm drive and ankle pop, and would jog back down for recovery. Toward the end of the workout I’d concentrate on time and was sweating like crazy even though it was winter and cold. I believe those two workouts were responsible for my maximum VO2 testing routinely I the 84 – 88 range and one time as high as 92. Even though my max VO2 was high another important number was anaerobic threshold. When my knee started bothering me in 1982 my threshold wasn’t as high because my biomechanical efficiency was off due to compensation for my left knee injury and I lost my ‘upper gears’ If I didn’t have a race or time trial I’d do a third hard workout which could be a 15-mile medium-paced run or a speed session of 200s or 400s. My training program was built around three hard training days a week unless there was a race. |

|

| GCR: | What do you feel is the relative importance of quality versus quantity in training and what was your typical training mileage? |

| CV | In the 1960s it seemed that U.S. middle and long distance runners were oriented too much toward speed and quick intervals. Then in the early 1970s the pendulum had swung toward more distance and the ‘LSD’ approach of long, slow distance. As a result, there were four to eight years where the U.S. didn’t have many sub-four minute milers. Then in the late 1970s and into the eighties we reached a happy medium. From the mid-eighties until somewhere around 2004 distance running suffered in our country at the high school, collegiate and pro ranks. When high school running started to improve in the late 90s and early 2000s it translated to more competitive collegians and then faster racers at the pro level. I think there has to be a balance between quality and quantity and a focus on aggressive, time-oriented racing, not just racing to win. If runners just run tactically and fast enough to win, they aren’t tested enough. In the late 1980s and early 1990s Todd Williams and Bob Kennedy were way out front and didn’t have too much competition domestically. I do feel that if you err on one side you should err on the side of quality. My high school training program consisted of 60-80 miles per week. If there were two competitions in a week it would be on the low end, one competition on the high end and in the off season the same. In college I went into the 80-100 mile range with my first 100+ mile week during my junior year. I would alternate a week over 100 miles with the week less than 100 miles. It may not be a coincidence that I won my only NCAA Cross Country title that fall and made the Olympic team the next summer. I also started doing my first 15-mile runs that year. I feel 15 miles is the most a runner should do unless training for a marathon. Post collegiately I ran three weeks of 100-105 miles in a row and then a recovery week of 85-90 miles. In the peak summer racing season post-collegiately I dropped to 70-80 miles per week as my intense speed sessions increased. I believe that all runners need some recovery time where they take time to recover and heal. A runner also must figure out as an athlete if he thrives on a bit more quality or quantity which is a decision determined by an athlete and his coach. |

|

| GCR: | What are your thoughts about the differences and intertwining of the ‘science’ and ‘art’ of coaching? |

| CV | I divide coaches into two categories – there are scientific coaches like Jack Daniels and Joe Vigil that are proponents of max VO2 training and long intervals. Many coaches follow that protocol. The other coaches I call the ‘artist coaches’ and I’d put myself in that category. This approach combines knowledge gained by experience and a little book knowledge with a huge dose of instinct and intuition thrown in for good measure. Some coaches are making training too technical and too complicated. I believe, like Vince Lombardi, that if you master certain basics and work certain systems that all will fall into place. I wish I could claim that there was some exotic formula, but it’s all out there. It’s like a chef – there are certain ingredients that go into a dish and its how you mix and match them that determine the outcome. That is how the mastery of the chef comes into the picture. That’s why I believe coaches should be more artists than scientists. It’s nice to have all of the scientific or medical testing and formulae that science coaches use, but running is more than that. Many high school and college coaches ‘eat that up’ as it’s all written down in black and white. It’s in front of them and they can turn pages and look at charts to see what they should be doing. But there are times that instincts and intuition need to kick in based on environmental, physical and mental conditions. Then you have to go with both your brain and your gut instinct. |

|

| GCR: | What were your favorite track season strength and sharpening sessions? |

| CV | My bread and butter sessions were 12 times 400 meters and six to eight times 800 meters. I also did the classic Pyramid of 400, 800, 1200, mile, 1200, 800, 400 for strength and mental toughness and was always faster on the way back down. This was the hardest workout I did on the track. When I did 400s I’d do a few at 64, a few at 63, a few at 62 and then the last one all out. The rest period was a 200 meter jog. One friend and coach, Steve Baker, showed me that in my workouts in July and August during my peak racing season that I needed more rest and faster repeats to hone my speed. He showed me that when working on true speed like sub-62 400s, sub-45 300s and sub-27 200s I needed more time to flush out the lactic acid and to give the muscles more rest and recovery. This led to some of my best sprint finishes. With the 800s I’d do them with a 400 meter jog. Sometimes I’d just come down the ladder with a 1200, 800, 400 or 1600, 800 and 400 for sharpening. One favorite was 600 meters with 400 at race pace and then sprinting the last 200 meters– coming through at 63 to 64 seconds and then changing gears. Another was ten 300s with gear changes at 100 and 200 meters. A final very important sharpening session was eight laps of ‘in and outs’ where I ran the straight-aways fast and slowed down slightly on the curves. At my best I did the two miles in around 8:40 so the straights were close to 4:00-4:10 mile pace whereas the curves only slowed to about 4:35 pace. |

|

| GCR: | Discuss the importance of negative intervals, ‘gear changes’ and following predetermined race strategy. |

| CV | A major emphasis in my training philosophy is negative intervals – whether on hills, the road, the track or grass I believe in getting faster as the workout progresses. The most simplistic is how I did them in high school where every one got faster. In college and later on I’d do sets where each set got faster such as 12 quarter miles with four at 64, four at 63, three at 62 and the last one at sub-60. If you do a pyramid workout you go faster on the way down than on the way up. I liked doing a repeat 600 meter workout where I did a lap at race pace of 63 or 64 seconds and then tried to run the final 200 at 28 seconds or faster. I believe this puts a runner in top form to change gears when needed during racing season. Some coaches think accelerations and gear changes come naturally, but for most athletes it is a learned skill. Changing gears is one of the weaknesses that most distance runners have. You have to be able to change gears at least twice – with about 400-600 meters to go and somewhere around the 200 meter mark. If it was a tight race you might need to find another gear in the last 20-30 meters. It takes a talented runner to have two gear changes and very few have three. Steve Prefontaine showed that as tough as he just was how hard it is to do three gear changes. In Munich in the 5,000 meters he changed gears with 400-500 meters to go. Then he did it again on the back stretch when he tried to pass Viren. When he went for a third gear change on the home stretch he tied up – even as tough as he was he couldn’t do three gear changes. Part of what he did was to not follow his own race plan. He had told the media he wouldn’t let the race go slow and tactical and he broke his race plan and let it go slow for half of the race. I learned much from this in that you just can’t change your race plan in the biggest race of the year. You go with the formula that got you there and then hope that even though they may know what’s coming that if you execute it well they can’t beat it. If Pre had done that he would have medaled – if he ran like he did against George Young in the Olympic Trials he would have been in control instead of giving the race to Viren. |

|

| GCR: | With your great success on the track, roads and in cross country, which was your favorite and why? |

| CV | Of the three competitive disciplines in racing – track, road and cross country – my first exposure, first love and last love will always be cross country. I don’t know whether it’s because I was born on a farm and love the country atmosphere, that the fall is my favorite time of year or that my stride was well-suited for such terrain. It just came naturally and I felt at home. |

|

| GCR: | While at the University of Illinois you won nine Big Ten Conference titles. How exciting was it to compete at the conference level and win multiple titles on the way to the NCAAs? What are some of your most memorable races? |

| CV | The Big Ten nucleus with Greg Meyer, Herb Lindsay, Stan Mavis, Steve Plasencia, Garry Bjorkland and Mike Durkin was top notch– everybody talked about Villanova and Oregon, but our conference had guys who influenced American distance running for ten years. One of the faults of runners in the Big Ten when I arrived at Illinois was that so much emphasis was placed on the conference meet that many peaked for conference and were on the downside by the NCAAs. Schools like Villanova, Oregon and Washington State seemed to do better at nationals and Big Ten runners underperformed. While I was there a transformation occurred and runners did a better job of peaking for several meets. My end-of-season ‘big meets’ started with the Illinois Intercollegiate Championships. I always wanted to race well, but without too much tapering. The Big Ten meet was important to coaches as the athletic directors put emphasis on conference results which may have impacted the coaches’ bonuses. In cross country, my season’s performance was always judged on conference, districts and nationals results. My first Big Ten victory was on my home course which was special and even more so since Illinois hadn’t had an individual champion since Al Carius, who became a legendary coach at North Central College after his running career. My first Big Ten track victory was my sophomore year at the University of Iowa in 1975 – it was even more exciting because in addition to my three-mile victory we upset Indiana for the team title after they had a three-year juggernaut to win by only one and a half points. My fourth Big Ten cross country title was tough as I was hurt and it was a stellar field with Herb Lindsay, Steve Plasencia and Greg Meyer. My senior year of cross country was difficult as I had raced from August of the preceding year for twelve months ending in August of 1976 after some post-Olympic meets. I took a few easy weeks and got back into training, but hurt my calf and Achilles tendon at a dual meet with SIU-Carbondale which haunted me the rest of the year. It happened partially because I hadn’t had a break. It affected me throughout cross country and track. I am proud of the fact that I’m still the only man to win four consecutive Big Ten cross country crowns. My senior season was capped off by my final Big ten title in the three-mile and then a second and fourth in the NCAA 5,000 and 10,000 meters. It was at Illinois and I gave it my all in front of the home crowd. It was tough as I had three races in three days with prelims and finals in the 5k and the 10,000 meter finals which was a lot of racing in 48 hours. The following week was the U.S. Championships at UCLA and I was so physically and mentally tired that I dropped out after four miles of the 10,000 meters while still in the lead pack. We all have our limits and I had reached mine – it was too soon for me after running 20,000 meters on the track the previous weekend. |

|

| GCR: | You were the top American in eight NCAA cross country and track events, but only won one title, the 1975 cross country crown due to the many top foreign runners in the U.S. collegiate system. What are your thoughts on whether the foreign runners help or hinder development of domestic talent and how fair is it to our top athletes, such as yourself, to miss out on national crowns? And how has Title IX affected collegiate track and field? |

| CV | I have maintained for 30+ years the same position - that the issue in the mid-1970s where some coaches brought in foreign Olympians who were in their early to mid-twenties was not fair. For 18 – 22 year old Americans to race against 24 year old freshmen wasn’t fair. I remember Suleiman Nyambui of UTEP having some gray in his beard. I was a World Champion at age 24 and it would not have been fair for me to race in college. When they changed the rule on the overage athletes it became fairer. Not to disparage the record of Steve Prefontaine who won many NCAA titles, but he didn’t have to race the older Africans to the extent those of us did in the mid-1970s. There were some Irish and English, but it wasn’t like when I was running and some coaches were going to the Olympics to recruit athletes. When there are only 12.6 scholarships for men participating in track and field, I think that too much aid is often given to foreign athletes. I think that foreign athletes can help the development of American runners, but if we are swamped with them it can be counter-productive. Many kids are left on the sidelines and don’t pursue track and field as a result of no financial assistance. There is no asterisk beside my name that says I was the top American in eight NCAA races. I have to hand it to Alberto Salazar as he was one American who wasn’t shaken by the foreigners. My senior year when he was a freshman and the NCAA meet was at Illinois I asked for his help and he did so for the first two miles of the 10,000 meters. My biggest two criticisms of the NCAA are first that when there is a situation that needs addressing they are slow to react and often take up to ten years to correct a problem. Secondly, Title IX has been interpreted poorly and football should be taken out of the equation. The interpretation with football in there results in having to take away men’s programs because you can’t make up for 85 scholarships. It’s caused men’s track scholarships to be cut to 12.6 and we need 18 to 24 to field a complete team. What has happened is that very few distance runners get scholarships and most are just partial. Many Americans who need assistance and development don’t get it. I am seeking a level playing field and the development of domestic distance runners. Then post-collegiately many runners who placed between fourth and tenth at the NCAAs were overlooked by the shoe companies for sponsorship even though they may have been in the top three U.S. runners. |

|

| GCR: | At Lebanon (Ill) High School you won five state championships, still hold the state cross country course record and broke Steve Prefontaine’s national outdoor two-mile record of 8:41.5 with an 8:40.9. Your success came fast – what contributed to your racing at such a high level when you didn’t start running until age 14? |

| CV | I grew up and worked on my family’s farm way before I was a runner. When your dad has 900 acres and you also have three to five acres of grass to mow you get used to a lot of work. I always told people that I’m a ‘white Kenyan’ as I had a much more vigorous upbringing growing up on my dad’s grain and livestock farm than most suburban kids. I think it definitely made a difference. First there was the lifestyle of my dad farming about 900 acres of hay, corn, soybeans and raising livestock – hogs and cattle. In grade school, high school and through part of college I helped. If you look at the Kenyan and Ethiopian runners, many of them grew up on farms and are used to a physical lifestyle where you learn to put up with discomfort. And what is distance running about? Putting up with discomfort while you get the job done – whether it is hot, cold, raining or dry - you have to get the job done and it was a background that suburban or inner city kids didn’t necessarily have. |

|

| GCR: | You were very consistent in high school, breaking nine minutes in the two-mile 15 times, a national record you share with Eric Hulst. Were many of these solo efforts and, if so, how did you focus on racing fast with or without competition? |

| CV | I was very naïve and innocent. I regard high school competition as pure running where you just go out every race and do your best. It has changed these days with so many top high school all-star meets. Now many of the pressures, sophistications and business-like approach have filtered down to the high school level. I broke nine minutes my senior year in every two-mile except one where there were thirty mile per hour winds as I went out every time to race fast even if there wasn’t anyone close to me. There were years in the 1990s and early 2000s where there was very little focus on times and it led to a decline in the quality of U.S. distance running. We lost the focus on aggressive running and tactics. In just running for victories it set us back like the LSD approach in the early 1970s led to fewer fast times for American milers. |

|

| GCR: | The ‘Craig Virgin Legend’ has you showing up as a high school freshman the day after your 14th birthday on August 3, 1969 for your first day of cross country practice and lapping the entire varsity team during at five-mile run which was 15 laps around a one-third mile dirt path. Is this fact or fiction? |

| CV | It’s all true. I owed it to my eighth grade basketball coach. I felt the only way I wouldn’t get cut from the team was to out-hustle all of my teammates on every running drill. The grade school, junior high and high school were side by side with a big field behind it that was a third of a mile around. My coach timed me and then went to the high school running coach and found out their times and only one or two were faster than me. One day he brought my dad in and said, ‘Craig should consider running cross country.’ He was kind for not saying that I was a pretty lousy basketball player who would just be collecting splinters. My first ‘running trophy’ was for stealing bases in baseball. I was a leadoff hitter who got on base, stole bases and did my best to score. For my first day of cross country practice I wore my junior high gym suit with my name in the block on front and my Chuck Taylor Converse All-Star basketball shoes. I broke away from the team and did lap them all. I did this for five days and then I was so sore that I could hardly walk. So I quit the cross country team and went out for baseball. I saw I couldn’t beat out the starting second baseman so I went back to the cross country coach and said I’d like to run just this one season and give it a try. The rest is history. |

|

| GCR: | With all of your high school racing success, championships and records, what stands out from your dozens of competitions? |

| CV | I won my first race against Mascoutah High School which was our rival and who we had never beat as a team. I started out in the back, worked my way up and had a side stitch for a mile that finally went away. With a half mile to go I passed one of their guys and someone yelled, ‘You’re in first place – if you can hang on, you can win!’ I won and when I asked what happened to Steve Watson, their top runner, they said he had to stop and go to the bathroom in the second mile. That taught me a lesson to always take care of that before the race! I didn’t make the State cross country meet that first year as at Sectionals on a narrow path I got stuck behind runners and finished outside of the top seven where I needed to place to qualify. In track I ran a 9:45 at District and 9:31 at State which were my first two national age group or class records. Our school only had 400 students and we had to compete in Illinois at that time against schools with over 4,000 students as there was only one classification. My sophomore year I was undefeated going into the State cross country meet and faced David Merrick who was the best distance runner in the country. I went out with him and faded to sixth. In track I went with him for five laps and did not fade though he beat me. I did finish in 8:57 which was the first time a sophomore and 15 year old had broke 9:00. My junior year I won the triple crown of cross country, 1-mile and 2-mile. My senior year I won cross country again and went for Pre’s two-mile record in track that spring. I just missed it by a second with an 8:42 in 88 degree heat. I came back and finished a disappointing second in the mile. A week later I ran a 4:05 mile and a week after that 8:40.9 in 94 degree heat in Chicago. I was so blistered up I couldn’t go to Golden West. Then I ran 13:34 for three miles at Junior Nationals in Gainesville, Florida. I went to Europe for three races. I ran 8:10 for 3,000 meters and was beaten by two Germans. In another 3,000 meter race I ran 8:15 against the Polish runners and won. Finally I ran 13:59 for 5,000 meters to beat the Russians. They had beaten me the year before by using team tactics so I got them back. One overriding factor in high school was that I had no preconceived notions about what my limits could be or should be. I went into every race to run hard. After my freshman year of cross country where I went out slow and passed people I changed to going out strong and trying to burn out my competitors. That developed my front running style that I used for the rest of my career. I ran at my pace and was able to drop runners most of the time and raced against the clock. When I ran the 8:42 Jim Eicken beat me to the rail and made me run on the outside of lane one for a lap and a half before I finally got around him and set off after the clock and Prefontaine’s ghost. When I look back on that, the time I lost on the outside of lane one may have cost me the record. Jim eventually became my teammate at Illinois and I always told him he owed me a steak dinner for that! |

|

| GCR: | Every great runner has coaches that contribute to mental and physical development. What did each of your coaches do to contribute to your success as a person and a racer? |

| CV | My high school coach, Hank Feldt, just celebrated his 50th year of coaching – his only background on running was two years of prior cross country coaching. He got his graduate degree under Coach Doc Councilman who developed Mark Spitz and the other great University of Indiana swimmers. Hank Feldt took two classes in swimming theory from Doc and the training is similar in that there are over distance days, interval days, tapering, rest days and racing. So that was the only formal training that Hank had and we learned together over that four years. There were times when he was coaching basketball in the winter and sometimes in the summer where I was on my own but I owe him a lot as far as work ethic and allowing me to try things and to spread my wings. In college Gary Wieneke was much more oriented toward mile and half mile runners so I helped educate him for longer race training. A lot of his development as a coach came by trial and error. Gary was a good coach for me. The first two years Gary set the workouts while the last two years it was more of a collaborative effort. It was good running there also as my family and friends could see me run. Gary’s administrative details for organizing practices, trip itineraries, record keeping and races are things I learned that I put to use in the future. After college I had a negative experience at Athletics West with Coach Harry Johnson as we didn’t get along very well. It was the only problem I had with a coach, but I did respect him for his work ethic. I think he had an extreme interpretation of the Arthur Lydiard training method, but others did too. I learned some good things that he opened my eyes to that I incorporated into my thesis that I wrote in Sept, 1978 on ‘How to Train to be a World Class Runner’ that I used for the rest of my career. But by early 1978 there just wasn’t the comfort level which I had with my previous coaches. In Europe that summer the discontent of my teammates was like a virus. Coach Johnson basically said, ‘I don’t care how you did it before, now you’re going to do it the Harry Johnson way.’ He didn’t ask us what we did to be successful earlier and I was used to having a cooperative effort with my high school and college coaches. Even though I ran some PRs, I knew I was going to have to leave the nice subsidized running lifestyle at Athletics West and go back home to Illinois. Two other coaches had an influence on me as they spent time with me when I was racing and training in Europe. One was the Santa Monica Track Club’s Joe Douglas who discussed training and racing with me at meets. He was a coach who was trained in Igloi’s method. Joe Douglas’ workouts were great for me during my peaking season when I needed fast track sessions that got me ready to take the gains of the months of training and focus it on fast racing. A guy who worked for adidas and later for Nike taking athletes to Europe that I respected was Pete Peterson. When I left college and Athletics West I relied on three coaches – Gary Wieneke, Joe Douglas and Pete Peterson. I’d go back and work with Gary Wieneke every couple of months for a few days because he had seen me at my best and worst and I needed a set of eyes that could tell me how my form looked. I’d talk to Pete and Joe on the phone about setting up my overall schedule based on the races I was pointing toward and they had a significant influence on my training and European racing schedule even though I made the final decisions. I’d set about 80-90% of the training and they’d help with the 10% of the polishing. Pete and Joe worked as a combination of mentors, advisors, and coaches for me. |

|

| GCR: | For most runners of your era, Steve Prefontaine was an inspiration. Did you meet him, what do you remember when you heard of his death, was his presence felt when you trained and raced in Eugene and how did his tragic end influence you and other top U.S. distance runners? |

| CV | I met Steve Prefontaine once and he was one of my running heroes. I chased his records and probably broke more of them than anyone else did in high school, college and post-collegiately. We ran in one race together which was the 1973 NCAA Cross Country Championships in Spokane, Washington which was my freshman year and his redshirt senior year. I only met him for a few minutes in a pool hall. He shook my hand and said something like, ‘You’re the guy who got my national high school two-mile record. You got it by about a second.’ I said, ‘Yes sir, Mr. Prefontaine.’ I got a chance to meet a guy who wasn’t my mentor as I never talked with him, but he was my role model on the track. An important differentiation – his racing style, commitment to training and commitment to developing his gift is what I wanted to emulate. I did not want to emulate his off the track lifestyle. I didn’t approve of it then or now and have some questions about the Nike advertising campaigns that have glossed over some of his lifestyle choices that contributed to his demise. He could not have kept up that lifestyle as he was burning the candle at both ends and having injuries such as sciatica problems. What he did at age 19 or 20 he could no longer do and stay healthy. He got beat a few times by other Americans and was no longer bullet proof – he was vulnerable. But he was still capable of bigger and better things. I first heard of his death when I was at the USTFF Championships in Wichita, Kansas. It was the weekend before the NCAA meet. We were in Wichita for a few days and when I woke up Saturday morning and went to the cafeteria to get breakfast everyone was talking in hushed tones. People asked me if I had heard what happened. I said, ‘What?’ They said that Prefontaine had been killed in a car wreck. The air went out of me with a sense of sadness and an intense feeling of responsibility that those of us who were coming up needed to pick up the baton and carry it. Several guys would now have to carry the torch he had passed, but we would be without our leader and had to grow up faster. I raced that night and got third in a 3-mile in a PR and got third the next week at NCAAs. At the national AAU Championships in Eugene I ran a 13:35 for 5,000 meters and got fifth or sixth in front of Pre’s crowd and it was special to run on the same track where he had left footprints such a short while before. It was a catalyst and a metamorphic event that helped propel me to my best collegiate running and making the Olympic team. Pre’s death was terrible, but gave me a sense of responsibility that I needed to step it up for our country and our sport. |

|

| GCR: | Who were some of your favorite competitors and adversaries from your professional career, collegiate days and when you first started in high school competition? |

| CV | When I look back at my career, so many of my big races involved Nick Rose. My junior year when I won the NCAA cross country championship I beat Nick Rose to do that. I beat him a couple times in college and he returned the favor. To beat Nick and John Ngeno sparked my readiness to make the Olympic team the following year. And of course there was the 1980 World Cross Country Championship race with Nick pushing the pace out front. Within the Big Ten my freshman year it was against Pat Mandera of Indiana who was the top conference runner. I was so tired when I beat him at the Big Ten Cross Country Championships that I could barely break the finish line tape and they carried me through the finish chute. He finished ahead of me at Districts and NCAAs that cross country season. Nick Rose and I faced each other in cross country and indoor track though outdoors we were usually racing different distances. We had two or three classic indoor duels where he’d out sprint me in the last half lap. He had a range from sub-1:48 up to low 28s for 10k. He was a great guy – up until the race he’d chat, joke and ask about your family but when the gun went off he was all business. When the race was over he treated you fair and square – if I beat him he didn’t sulk and if he won he didn’t lord it over the other runners. I admired and respected him for that. I saw him a few years ago and it was great to visit with him. John Ngeno, Samson Kimombwa and Josh Kimeto of Washington State were also tough adversaries. When I was in Africa a few years ago for a junior race Josh took a five hour bus ride to visit me and helped me buy some souvenirs for my family. It was neat that he had as many fond memories of our collegiate competitions as I did. Matt Centrowitz and I had a rivalry a bit as in the race where I broke Pre’s two-mile record he was second in 8:57. He went on to be an Olympian and U.S. champion and in 1981 we had an epic 5,000 meter battle at the national track championships where he beat me in the last 200 meters. In high school Dave Merrick whomped on me my first two years and it taught me a lot as he showed me the difference between being good and being great. Another Big Ten rival was Tom Byers. There were probably six or eight Big Ten rivals who went on to greatly influence American distance running. I’m proud to say I ran with them and against them. |

|

| GCR: | You had a congenital urological disease that caused health problems beginning in early childhood and which culminated with your right kidney being removed in 1994. What was the effect on your running and racing and does this still affect you now? |

| CV | I was diagnosed at age five with a congenital kidney disease and went through reconstructive surgery and annual testing that wasn’t pleasant. From the age of five I took daily oral antibiotics and had to learn to self monitor my urological system to tell my parents and doctors when I needed to go to the hospital for intravenous antibiotics. The testing and treatments involved pain and discomfort which helped me learn to disassociate from pain and tolerate discomfort. The medical problems I faced between age five and thirteen helped me accomplish what I accomplished. The mental ability to tune into my body or tune out to get tasks done on the farm or tests done in the hospital gave me a skill set that helped me as a runner to get through a long grueling workout or an intense race. At age 13 they surgically remodeled my bladder and reinserted the ureters in November of 1968 and by early 1969 the reflux that had caused the recurring infection had stopped. My right kidney eventually developed a kidney stone that would often position itself and be painful or cause an infection. I’m not sure if the removed right kidney in 1994 and loss of filtering ability affects me now as I haven’t been able to train with much regularity or intensity. Since the byproducts of intense exercise are filtered through the kidneys, I would think it would affect me some if I was physically able to train intensely. |

|

| GCR: | A violent head-on car crash in 1997 nearly killed you and led to eight operations in the next two years. How tough was the rehabilitation process and do the lingering remnants of that day affect your current health and fitness? |