|

|

|

garycohenrunning.com

garycohenrunning.com

be healthy • get more fit • race faster

| |

|

"All in a Day’s Run" is for competitive runners,

fitness enthusiasts and anyone who needs a "spark" to get healthier by increasing exercise and eating more nutritionally.

Click here for more info or to order

This is what the running elite has to say about "All in a Day's Run":

"Gary's experiences and thoughts are very entertaining, all levels of

runners can relate to them."

Brian Sell — 2008 U.S. Olympic Marathoner

"Each of Gary's essays is a short read with great information on training,

racing and nutrition."

Dave McGillivray — Boston Marathon Race Director

|

|

|

|

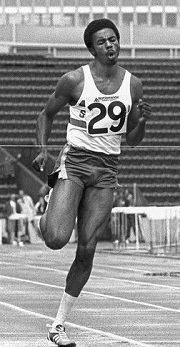

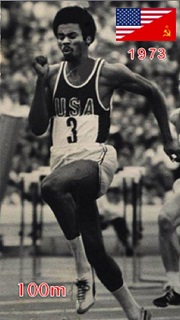

Steve Williams was a two-time Gold Medalist at the inaugural IAAF World Cup in 1977 in the 100 meters and as anchor leg for the World Record setting 4 x 100-meter relay. He is listed ten times from 1973 to 1976 in the 'Progression of World Best Performances and Official IAAF World Records.' In 1973, Williams ranked number one in the world at both 100 meters and 200 meters. For the six-year stretch of 1973 to 1978, Steve never ranked lower than fifth in the world at 100 meters and ranked first or second in the U.S. at both 100 meters and 200 meters. At the 1973 USA-USSR Dual Meet, he came from behind on the anchor leg of the 4 x 100-meter relay to run down 1972 double Olympic Gold Medalist, Valeriy Borzov. In Jamaica, Steve won the 1975 Martin Luther King, Jr. Freedom Games and the 1977 Jamaican International Games. He was three-time Gold Medalist at the Zurich Weltklasse Games, at 100 meters in 1977 and 1978 and at 200 meters in 1980. Steve was AAU double Gold Medalist at 100 meters and 200 meters in 1973, defended his 100-meter title in 1974, and added the 1976 AAU indoor 60-yard title in 1976. Olympic glory was thwarted by injuries in 1972 and 1976 and the U.S. boycott in 1980. He raced collegiately for UTEP and San Diego State, winning the NCAA 100 meters in 1973 and anchoring the Penn Relays 4 x 200-meter champions in 1974. At Evander Childs (New York) High School, Steve set the New York State record in the 100-yard dash at 9.4 seconds and was U.S. Junior Olympic Champion for 400 meters with a time of 47.2. His personal best times are: 100 yards – 9.1; 100 meters – 9.9 and 200 meters – 19.8. He was inducted into the U.S. Track and Field Hall of Fame in 2013 and San Diego State HOF in 2016. Steve resides in San Francisco, California with his wife, Flavia, and was gracious to spend two hours on the phone in the summer of 2020.

|

|

| GCR: |

Athletes leave their stamp with championships, memorable races, and records. While one individual World Record is momentous, what does it say about your career as a sprinter when you are listed ten times from 1973 to 1976 in the 'Progression of World Best Performances and Official IAAF World Records?'

|

| SW |

I was very, very, very fortunate that I even got the chance to run the one hundred meters. I’m almost six feet, four at six feet and three-quarter inches. The difficulty in pulling my height into the one hundred meters made me very proud that I had World Records at that distance. One of my most memorable records is my World Junior Record for 400 meters when I broke forty-five seconds when I was only eighteen years old. In many of my races, the emotional part of the one hundred meters was the only thing that mattered. I had to get emotional, get my adrenaline up and have that out-of-body moment the last forty meters. The records just came because I was chasing fast guys. I’m humble about it because it started so early in my life when I was only eighteen years old. I just thought you run fast, they will tell you the time and you say, 'Okay - let’s go back to work.'

|

|

| GCR: |

Speaking of running fast and especially during the last forty meters, I watched several of your races again on tape this week. Championship races are memorable not only because an athlete wins, but how he wins. Can you take us through the 1977 World Cup 100 meters race where toward the finish it came down to Eugen Ray in lane two and you in lane one and you passed him in the final ten meters to win the Gold Medal by three-hundredths of a second which reminded me of Dave Wottle winning the 1972 Olympic 800 meters by that same three-hundredths of a second?

|

| SW |

I had been injured in 1976 which was a heartbreak for me as I had been national champion in the sixty-yard dash indoors and had run 9.9 three times and 19.9 twice prior to the Olympic Trials. Surviving from that point of my injury in 1976 until 1977 with that race against Eugen Ray, there was no way I wasn’t going to catch him if he was the one who was leading the race. When the gun went off, I thought, ‘He’s not that far out.’ I composed myself and I knew I was going to catch him. Not being able to see Silvio Leonard in an outside lane was my only possible miscalculation. But I was going to run Eugen Ray down. There was nothing but that passion that comes from being in the middle of a good one hundred. The passion takes over.

|

|

| GCR: |

In that same 1977 World Cup, in the 4 x 100-meter relay, Bill Collins, Steve Riddick, Cliff Wiley and you turned in a World Record Gold Medal performance in 38.03 seconds. From your vantage point standing in the final relay zone on the curve and watching the first three legs, can you take us around the oval with your thoughts as the first two passes looked very good, Wiley’s handoff to you was safe and then you exploded your anchor leg down the home stretch?

|

| SW |

The back story on the relay is amazing as Steve Simmons, the national coach pulled together the relay team and I was kind of the wild card. I did not participate except for one of the pre-World Cup relay team races. At the meets I was running one hundreds and two hundreds. I wasn’t running the relay much. When I was waiting to get the relay stick, Steve Riddick ran the kind of back stretch where, as an admirer of track and field as well as a runner, I literally stood up and had my hands on my hips watching Riddick run that back stretch. That record is about two big guys running as long as possible in the zone. Riddick took the stick early from Collins and handed it deep in the zone to Wiley. I took it from Wiley as soon as possible. So, we fudged maybe a hundred and three meters apiece on me and Riddick. Collins and Wiley were solid sprinters but, on the clock, they weren’t the fastest guys. I tip my hat to Coach Steve Simmons on that. Borzov happened to be on the anchor leg for the European team and I got reminiscent of the first time Borzov and I met on the relay which was in 1973 at the USA versus USSR meet. I had my blood boiling when I saw him lining up. I was so excited to run that day. It was a great time for us, and we had modest stick passes. The most important factor was there were no heats, no semi-finals, one race on a cold night and we broke the World Record. If we could have run another race twenty minutes later, we would have broken thirty-eight seconds and been the first team to break into the thirty-sevens.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned that 1973 race against Borzov and there is a cliché we have heard often that proves true and it is, ‘To be the best, you have to beat the best.’ How exciting was it, especially as only a 19 year-old, to anchor the 4x100 relay at the USA-Soviet dual meet in Minsk and to run down Valeriy Borzov, who had earned Gold Medals in both the 100 meters and 200 meters a year earlier at the 1972 Munich Olympics?

|

| SW |

I was so broken-hearted in 1972. As an eighteen-year-old freshman in college, I had a spectacular year. I ran 6.1 for sixty yards and 9.2 windy for a hundred yards and 20.2 for 220 yards and 44.9 for 400 meters. I was in phenomenal shape and didn’t feel young at all. I had been training all my teenage years and there I was. Every place I went. I was so excited to be at the top level of track and field. My excitement made me run fast and chase down good guys. And then I got injured. Just knowing that Borzov had the two Golds while I was nursing my leg in 1972 made my passion to jump on him unbelievable. We knew all the Russians and all the East Germans were ‘steroided’ up. There was no question in our minds… We knew it and that was part of where we had to work. I can say, the only thing that saved me when I knew that other guys were juiced up was passion. The passion to win. When I saw Borzov in front of me in 1973 at nineteen years old, the passion to jump on him was unbelievable. I speak of this and put it into another world perspective. This was about the Americans, my men Rey Robinson and Eddie Hart being cheated and not making the Munich final. It was also the United States against communism. But also, this had a racial component, black against white. I can’t tell you the amount of responses I had after that race for many a year. It was the passion to run down whoever was in front of me and, with Borzov, I had an extra dose of passion for him.

|

|

| GCR: |

That is very cool how there were three components of passion in the thought process going on inside you and how you channeled it into amazing emotion. Speaking of beating the best… at the 1977 Jamaica International track and field meet you won the 100 meters into. a five- mile hour wind and beat two Olympic champions, Hasely Crawford and Don Quarrie, other finalists from the Montreal 100, and Steve Riddick, Houston McTear, and Cuba’s Sylvio Leonard. What do you recall from that race and others in Jamaica and how exciting was it and emotional to beat that strong a field?

|

|

|

My history in Jamaica is phenomenal. In 1973, I went to Jamaica at the end of the season in October on an AAU trip. When I got off the airplane, there was a big poster that said, ‘Will it happen again?’ The picture was of Donald and me in one of our previous races where I had beaten him. I thought to myself, ‘Oh Man, I’m not in shape. I’m back in school again. I’ve walked into a trap.’ I knew I could always run a hundred meters, so I decided I would run the hundred, but no two hundred. I told the AAU officials what I was going to do. Before the race I’m warming up and, suddenly, I’m surrounded by the police. The military police walked me up the stadium steps to what is now called a skybox to meet Prime Minister Manley. They took me out of the warmup area and up to meet him. I shake his hand. He is cordial. Very political. A politician straight up and down. I told him I was sorry that in my condition I couldn’t run the two hundred and I wouldn’t put in a good performance. He went into a political diatribe, ‘The people have come from the red hills,’ and on and on about the people coming from all the parts of Jamaica to see this race. I told him that physically I wasn’t prepared, and he said, ‘Is there something we can do financially?’ I’m getting ready to tell him how much because I was waiting for this moment, though not from the Prime Minister. I was ready to say how much and an Asian guy said, ‘I’ll handle it and you can take an extra hour to warm up. Donald ran and won in 20.8 seconds and I ran about 21.5, a high school time. From that point forward, I would never go to Jamaica and not be ready to go. That was the wake-up call. Don’t ever go anywhere that somebody is a national hero and go into his country unprepared. In 1975 it was a memorable one hundred meters because all the top guys were there also. It was the Martin Luther King Freedom Games in 1975 and McTear had just run nine flat for one hundred yards. As a nineteen-year-old he came down to Jamaica to bravely show his stuff. It was the first time we had lain eyes on him. He took off and was leading the race. I think I caught him at ninety meters. So, when people talk about whether youngsters should race top competition at eighteen or nineteen and they are hiding these kids – jump up and show your stuff. It’s not boxing. You aren’t going to get knocked out. In 1977 I was working to get back in shape and to chase everybody down. Donald Quarrie and Hasely Crawford had the Gold Medals and it warmed my heart because I have big love for both those guys and what it did for their status in their countries. Whether I would have beat them or not, we will let history decide one way or the other. In 1977 I was there to reestablish myself, to chase everybody down and to be in shape again. It didn’t matter who was there but, as usual, to try and catch the people in front of me.

|

|

| GCR: |

There is a venue that we must talk about where I was fortunate to be a spectator in 1998 and that is in Zurich, Switzerland. You had some big races there. In 1977 you beat Quarrie and Riddick and Wiley and Ray while in 1978 you took the lead early after about sixty meters and won big going away. Did you like racing in Zurich which was almost like a one-day Olympics as the promoters brought in such great fields in every event?

|

| SW |

Zurich had its place as the top track and field meet for many reasons. One was the neutrality of Switzerland. My biggest frustration any time someone would mention Borzov was the amount of time he would spend hiding. He would never show up. Silveo Leonard would hide, duck and dodge and never show up. But everybody would show up for Zurich. Also, if you were working on your World Ranking, you had to win Zurich on the European tour to get that bump in your ranking. That was considered a known fact. We showed up for Zurich and, as you said, it was a mini-Olympics. Mr. Brugger, the meet promoter was a gentleman. He was the Godfather of this whole Golden League. He was a great man and he died a couple years ago. I would go to Zurich and Mr. Brugger and I would make bets. I might be in so-so shape having won a few races and lost a few by the time I got to Zurich. He would ask me what we were going to do, and I would tell him. One time he said, ‘Steve, I’m not going to just give you chicken shit.’ What an exciting venue. There were so many world class performances that came out of there. The crowd was unreal.

|

|

| GCR: |

In 1980 in the two hundred meters you were out in lane seven with Don Quarrie and Mike Roberson just to your inside and Steve Riddick on your outside. Mike Roberson came out of Winter Park High School in Orlando and graduated the same year I did in 1975, so I was familiar with him. Roberson made up the stagger so fast and led with Quarrie second and you back in fifth or sixth place before you exploded in the last fifty or sixty meters to win by four meters. Was that one of those races where you were just off the charts that last stretch?

|

| SW |

When we had the chance to pick lanes in Zurich, I would always pick one of the outside lanes. A lot of times in Italy they would put Pietro Mennea behind me so I got used to being out there and would select an outside lane al by myself. When Roberson and Quarrie came off the curve like that, what saves me the last part of the race is I’m a four-hundred-meter runner. A legitimate four-hundred-meter runner. That makes running down people in the last sixty meters of a two hundred nothing compared to the pain of running somebody down that same part of a four hundred meters. I recommend and I’m glad to see the young boys now running a hundred, two hundreds and four hundreds. They’re breaking ten seconds, twenty seconds and now they are breaking forty-three seconds. You must be an all-distance sprinter. You must be able to do all that. In Zurich and in many of my finishes, I’m a four-hundred-meter guy. If my form doesn’t break down, and I don’t get sloppy, in all my two hundred-meter finishes, I’m glad I was a quarter miler.

|

|

| GCR: |

We mentioned the World Junior Record you set for 400 meters. Looking back, as good as you were in the 100 and 200, could you possibly have been even better in the 400?

|

| SW |

John Smith, the famous World Record Holder for 440 yards, came to me one time. I had trained with him for two days in 1975 - he and Milan Tiff, NCAA triple jump champ from UCLA. They were doing phenomenal weightlifting. They were doing weightlifting I wouldn’t even attempt to do. John Smith sat me down and said, ‘Steve, you can run forty-three seconds.’ At the time, the only forty-threes were Lee Evans and Larry James in the 1968 Olympics. I had absolutely no belief for anyone and particularly for me. The four hundred meters was and is a man’s race. It’s a hardcore race. If you can sprint instead of running the four hundred, everybody chooses to sprint. Usain Bolt and I had a talk in 2015 in New York. His coach, Glen Mills, was working together with Brooks Johnson and Mills was using some of the workouts to train Usain Bolt that I used to do. Usain and I both looked at each other with the same look on our face that said, ‘Hell no to the four hundred meters.’

|

|

| GCR: |

Steve, you mentioned how running in Zurich was important for World Rankings. One area I always focused on when I coached others was consistency in training and racing and results. For the six year period of 1973 to 1978, you were ranked in the top five in the world in the 100 meters each year with two first place rankings and were number one at 200 meters one time along with U.S. Rankings of first or second all six years at both 100 meters and 200 meters. What does it say that you were able to be so consistent, to be there and to be ‘The Man’ that everyone had to try and knock off the pedestal for those six years?

|

| SW |

There were so many ups and downs and there was an unbelievable back story every step of the way each year. Every year there was something else. There was somebody else. Also, the business side of track and field and my untold stories on the business side were hair-raising. I had no agent. I had no manager. I started off at nineteen years of age negotiating with the Prime Minister of Jamaica. I was placing bets with Mr. Brugger. For all the meet promoters, I have different stories. Some of my consistency was because I had to go to Europe, this was the time I had to work and be very professional in this amateur sport.

|

|

| GCR: |

It's amazing that you had to contend with this at that time and it is so different than it is now. You had to contend with trying to make money in a sport that was supposedly amateur and competing with athletes from other countries that had chemical advantages. How tough was it on you trying to earn a living and to compete with athletes that were cheating the system?

|

| SW |

It was outrageous that there was no sponsorship of American athletes. It was a civil rights issue. I started off in New York running for the New York Pioneers Club when I was fifteen years old. John Carlos used to come down and train and so did Norm Tate and Mel Pender. Anytime guys would come in town to race at Madison Square Garden, they would train at the Stevens 365t h street armory in Harlem. So, I was around John Carlos and the whole movement from as early as I can remember in my track life. Fighting over money was like a civil rights issue for me. I sat down guys like Edwin Moses and told them how to try to make money in this business. I was the guru behind the scenes. Puma was getting ready to lose Renaldo Nehemiah at the Millrose Games and the Puma rep came and told me, ‘Steve, you’ve got to call the owner of Puma. Otherwise we’re going to lose Nehemiah.’ I was behind the scenes because I dealt with everybody. Horace Dassler at Adidas, God rest his soul. Armand Dassler at Puma, God rest his soul. The balance between the Dasslers, with a billionaire company in Adidas and Puma worth about six hundred million dollars and these guys were fighting, arguing, and concocting schemes behind the scenes to get me to wear their shoes. And I didn’t have an agent. They were flying me in Lear jets to try to get me to sign contracts. People keep telling me to write a book about the behind the scenes stuff. There are interesting stories that I need to get out for posterity.

|

|

| GCR: |

We touched briefly on you missing the Olympics due to injuries and the boycott. There were quite a few outstanding U.S. athletes during your competitive years such as Craig Virgin, Renaldo Nehemiah, Don Paige and Steve Scott that missed out on possible Olympic medals or championships because they were too young in 1976, victims of the 1980 Olympic boycott and past their prime years in 1984. In retrospect, does missing out on the Olympics leave a hole on you resume or do your World Records and great races trump the fact that the timing of the Olympics every four years didn’t quite work out for you, as with some of these other great athletes?

|

| SW |

1980 is another story all together. I had taken off 1979 to prepare for 1980. I had an ankle operation and a bone spur. I was down in San Diego running the beaches in December of 1979. I had sold one of my investment cars and had enough money that I didn’t have to do anything but train. I was jumping rope, wearing a twenty-five-pound weight vest, when Jimmy Carter announced that we weren’t going to the Olympic Games. It was one of those moments where you never forget what you were doing. That’s what I was doing, jumping rope with a twenty-five-pound weight vest in front of a small television when Jimmy Carter announced the boycott. I pieced together 1980 and I got to the Olympic Trials. I got sixth place and I qualified for the relay. I remember Mel Rosen coming to me and asking me to sign papers and pick up my uniform. He knew I wasn’t going with them and was going to be racing in Europe on my own. I had such disdain that I left, and I was in Europe two days later. I did an eight-track meet tour of Europe in 1980. I was heartbroken like the rest of the athletes, just heartbroken. As you said, it isn’t like now with the World Championships every other year. We had to wait four years like we were going to college all over again before the next Olympic year. My wrapping it up was that in 1980 we had to be professional that year. We couldn’t be idealistic because the Olympics were gone and what do we do next? So, how do I feel about the whole situation? Do I feel like the football players who don’t have a Super Bowl ring? I know that my competitors in all the Olympics where I wasn’t involved, including 1972, know that they had a better chance because I wasn’t there. Each one of them. I take solace in that. Also, in comparison to the other sprinters, I feel love all over the world. I’ve been everywhere. I have records in Europe. I have records in five different states in the United States. I pioneered running in Taiwan in the 1970s. What it exposed me to is priceless.

|

|

| GCR: |

Let’s go back to 1973 and discuss a few races while you were still in college. First, is your first sprint World Record when you tied the mark for one hundred yards at 9.1 seconds. How was that to have World Record after your name when you were a young man and only nineteen years old?

|

| SW |

In 1972 I was World Record Holder. I was in class one day in El Paso and the campus police came and took me to the office because a famous writer from the cheet, Mr. Pariente, wanted to interview me over the phone because I was junior World Record Holder in the 400 meters. Oddly enough, when he said that, it was the first time I realized I had run the World Junior Record three days earlier. I didn’t even know. In 1973, I transferred from El Paso to San Diego State and was fortunate to hook up with Gold medalist Barney Robinson, Wes Williams, and Harold Williams. We had a strong nucleus at the San Diego Track Club. We were supposed to go to the Martin Luther King Games, but they were cancelled. We begged our way into the meet in Fresno. I didn’t know if I was going to get a lane in the one hundred until maybe two hours before the race. Herb Washington was there, and Herb had been a bit of a showoff during a couple of indoor races where I ran against him. He had every right to show off because Herb was the king indoors in the sixty yards and sixty meters. So, I had a little passion to race Herb. In the heats I ran 9.1 windy. They tried to say it was a clay track, but it was a dirt track. I don’t like dirt tracks at all, and I was happy to get through it. When they said it was so fast, I thought, ‘Okay.’ I had run a 45.9 with the san Diego Track Club in the Coliseum about two weeks before, so I was in quarter mile shape also. When Herb got out, the crowd in Fresno was unbelievable. I caught him and got into one of those expanded time moments. One second made you think in nanoseconds. The word, nanosecond, wasn’t out there yet, but that describes some of the sensations I had during the last forty yards or meters of a race. My adrenaline gets up, everything slows down and it’s like I’m stepping in between the seconds. That was one of those experiences. I have a lot of times when I have seen Usain Bolt do that and I’m probably one of the few people who understand it. When you get at top end in a hundred, it is like when you are on a motorcycle. It is exhilarating. You almost want to look to the left and to the right to see what it looks like, to see everything a blur on your left and your right. So, you look around. Regretfully, when I ran 9.1 against Herb, I got so euphoric that I looked back. It’s one of those times I wish I hadn’t because, if I had known I was going that fast, I would have leaned like crazy just to get that nine flat.

|

|

| GCR: |

In 1973 you accomplished a feat that hadn’t been done in over twenty years by winning both the 100 yards and 220 yards events at the AAU meet which Ray Norton had last done in 1960. Did you take a lot of pride in the fact that you were doing both races and not focusing on just one like many of your competitors?

|

| SW |

I was a quarter miler. But I left high school with the New York State record in the 100 yards at 9.4 seconds. Then I was national Junior Olympic Champion with 47.2 in the four hundred. When I went to El Paso, three of the guys failed out of school, so I got a chance to be moved up and be considered as a sprinter. I was there to be their quarter-miler. My coach, Wayne Vanderburg, one of my dearest friends to this day, looked at me and saw Tommie Smith. He first saw me running in 1971 at the Penn Relays and said, ‘There’s Tommie Smith.’ He had that eye for talent. I wasn’t supposed to get anywhere near the hundred except that people started to let me in the races. As far as the double at the AAU meet, I knew I was going to win the two hundred. I had to make sure that I had a better start to win the hundred. There were three rounds in the two hundred and that didn’t mean anything. To be double champion at nineteen years old, and that record still stands, nobody that young has been a double national champion.

|

|

| GCR: |

There is probably a very slim chance that will happen again as professional runners are able to run and make money now into their late twenties and into their thirties. I don’t think your feat will be matched.

|

| SW |

The other factor is that every time someone comes up that is fast at eighteen or nineteen years old, everyone tries to micromanage the kid. My feeling is where I came from in the Bronx is that, if a guy says he’s faster than you, you’ve got to race him at any age. Being young didn’t have anything to do with me as I was very mature with my craft of running. I was sloppy out of the starting blocks, I had wild arms and all those things I wanted to clean up. But at nineteen my passion for running and my fitness gave me confidence to go against anybody. I am proud of the double national championship at that age and that it is still hanging around as an achievement.

|

|

| GCR: |

Sometimes there are races that are super close that we enjoy as fans. There was one the next year in 1974 that you didn’t win and that was the 1974 NCAA 100 meters where only three hundredths of a second separated Reggie Jones, you, Steve Riddick, and Clifford Outlin. Did you have an off day or any injury problems and how was that competition with four of you within an eyelash of each other?

|

| SW |

For that NCAA meet in 1974, the back stories were all over the place. It’s amazing to be out there for only ten seconds with all the work that went into preparing for the race. I had a strained groin and all it affected was my leaning. It wasn’t affecting my running, just my leaning. In the heats of that race, I ran an extremely fast time, but it was wind aided. I was prepared for a good race. Reggie is a big, strong guy and when we get to the matter of inches in the last part of a race, it’s about how long our stride is. It’s about how our rate of deacceleration is not as great as the other guys. I was there just rolling along beside Reggie and we both had the same stride length. Great race and he got me, he got me. And close races – that’s part of the business, especially for me. I was always coming from behind. I was always winning by an eyelash. As I was explaining in sort of a psychic point of view, I started doing meditation in 1975 because I was having these out-of-body experiences where time would stop in the middle of the race and I started seeing things in nanoseconds. I wanted to do that all the time, so I started meditating. It is one of those adrenaline reactions. The excitement from the adrenaline in those instances is because everything is all slower than normal. You can see things better than you could ever see anything else. The adrenal gland is connected to our basic gland of fight or flight. When I explain to kids about competing, I often head them say, ‘I get afraid when it is time to compete.’ I tell them that I had to learn how to make fear and anger my friend. When you step into a stadium there are only two things that create adrenaline in human performance – fear or anger. A mother picks up a car that is resting on her child with superhuman performance or a man punches through a wall with anger. One of the two of those emotions triggers the adrenal gland, and I knew that. I would walk into a stadium and feel angry. Or I would walk into a stadium and be afraid. When one of those emotions hit me, I would think, ‘Okay, we’re ready to run.’

|

|

| GCR: |

We talked about that World Record relay race at the World Cup, and you did run many relay races during your career. One of my favorite relay races is the four by 220 yards which my Carol City High teammates did and qualified for our Florida State meet. In that race a bad pass wasn’t as disastrous, it wasn’t so fast as the one lap relay which took pure speed, and it wasn’t as long as the mile relay where some of the guys died in the homestretch. Did you like that four by 220 relay?

|

| SW |

My favorite four by 220 relays were at the Penn Relays. When I was at Texas El Paso we ran there. At UTEP in 1972 at the Penn Relays, I’m running anchor leg against Larry Black.

|

|

| GCR: |

I remember Larry very well as he was out of Miami Coral Gables and a few years ahead of me in high school.

|

| SW |

I’m laughing now because I’m nineteen years old, I’ve run 20.3 and I’m in the Penn Relays against Larry, God rest his soul. He gets the stick and is in front by maybe eight yards. I immediately jump on Larry’s butt and I’m next to him in the first eighty yards. And he takes every yard back from me in the last forty yards because he was so strong. That was that and we got second. We were supposed to run the mile relay next and one of our guys got hurt and we had to scratch from the mile relay. Otherwise, I would have been lunch meat for Larry when he ran forty-three low at the Penn Relays. We weren’t running so I was in the stands. The four by two hundred is a fun race because, as you said, there is a chance for speed and conditioning, stick passes are relatively safe and it’s not long like the mile relay where people die in the stretch. In 1974 when I ran with San Diego State, we came back to Penn and got the Gold in the four by two hundred. The Penn Relays has the most beautiful curve and that big crowd. I have affection for the four by two hundred, but particularly at the Penn Relays.

|

|

| GCR: |

Let’s go back and discuss your coaches and what they did to help you either with running technique, becoming a man or with your racing form. When you were young, you had several coaches in New York including Frank Magliardi, the director of a NYC Parks playground, Evander Childs Coach Duke Marshall and Melvin Clark, a policeman who coached in the PAL and AAU programs. What did these gentlemen do to groom you into that young man who ran 9.4 for 100 yards and a 47.2 quarter mile in high school?

|

| SW |

When I got interested in running track around 1967, I was fourteen and they used to have the Wide World of Sports on television. It was on a Sunday and I would go to a Catholic school, where I used to go, called Cardinal Spellman. It was right behind the projects. I lived in a middle-class home, but it was a half mile from New York’s Edenwald projects. The Catholic school had a big, beautiful track made of asphalt and I used to climb the fence to run at that track. I didn’t know anything about coaching. Not a thing. I said to myself, ‘I bet you they’re running ten times one hundreds.’ So, I would run twenty times one hundreds. ‘I bet you they’re running ten times two hundreds.’ So, I would run twelve. I just started running reps. Reps, reps, reps. But, as a young boy, when I was maybe nine years old, Coach Magliardi, who was the operator of Public School twenty-one in the Bronx, he gave me one comment that stayed with me. There were about five of us standing around and we were all eight or nine years old and we asked him what we should do. He said, ‘Don’t let any of the other kids be ahead of you in the end.’ That’s all he said and that became my guiding principle. It was just that simple. The police athletic league in New York used to time the kids and give out t-shirts and medals. Police Officer Clark saw me when I was about twelve or thirteen and he said, ‘I think you can do this. I think you can be a good runner.’ He helped guide me through some of my time in my early teens. Then my Coach Duke Marshall at Evander Childs High School taught me more about being a showman and promoting and being a standup black man and being proud. He wanted me to go to an Ivy League college and sent me to every school. Some of the recruiting stories are hysterical. I had coaches the next year tell me, ‘If I knew you were going to run like this, I would have changed your grades to get you in.’ Duke Marshall was particularly important to me.

|

|

| GCR: |

At your first collegiate stop at Texas El Paso, what did Coach Wayne Vanderburg do to help you progress?

|

| SW |

Wayne Vanderburg took me out of the Bronx put me on the track in El Paso with ninety degree sun all year around and put me with a bunch of great sprinters to compete against and practice with and that was great. To be able to train with great people and not have to deal with the New York weather moved me forward.

|

|

| GCR: |

Didn’t you get some help from Brooks Johnson when you were competing internationally in between collegiate seasons?

|

| SW |

In 1973 on the USA tour we went to Munich, Torino, Minsk, and Dakar. Brooks Johnson and I got awfully close. I liked his philosophy and I liked how cool he was. I had some battles with the AAU and a rather public battle with Ollan Cassell when we were down in Senegal. Brooks came in and mediated. Brooks used to coach me over the telephone. He would give me instructions and tell me to write them down and let him know what I did.

|

|

| GCR: |

When you returned to the U.S. for your next collegiate season, how was the switch in schools and coaches?

|

| SW |

I went to San Diego State with Coach Dick Hill and he was a disciplinarian who had all the particulars where I had to follow the NCAA rules and I don’t fault him for that. But at that same time in 1974 I had too many opportunities and running for a college was getting in the way. In 1974 I left San Diego State rather abruptly and Dick Hill and I went our separate ways. I always get a chuckle when I hear that some athlete turned pro because when I left San Diego State that was me turning myself pro.

|

|

| GCR: |

Why did you gravitate back to Brooks Johnson as your coach and what did he do differently with his workouts to help you to fine tune and to get that extra few percent improvement as a runner?

|

| SW |

Brooks and I had a long relationship. I like Brooks’ style. He has a Zen Buddha kind of approach. In 1975 I decided to go down to Gainesville to train until 1976. We had phenomenal workouts. Breathtaking progress was being made in all areas. If I could say one thing, I should have run less in Gainesville. I got to a point where I was fast enough. I was national champion indoors in the sixty that year. I had run 44.5 at the Penn Relays. I should have held back. I ran a little bit too much that year. I had good coaching and, more importantly, good men as friends who were leaders and big thinkers. Brooks was a big thinker. We did a shoe contract with Puma in 1976 which revolutionized the whole pay scale in track and field. Brooks and I ended up having a business together and a clothing company. The coaches came around and were good solid individuals that helped shape me as a man as well as to be a better athlete. Coach Vanderburg at El Paso put together the great group of athletes to train with. I was training with Mike Frey, from Jamaica, who got fourth in the 200 meters at the 1968 Olympics. Mike was six feet, four inches or six feet five. For me to be training running repeat two hundreds with Mike Frey and he was such a big guy, I learned how to run big. Coach Vanderburg put together the talent and we fed off each other. My start was notorious because of my height and I so enjoy and am jealous of Usain Bolt – not the running, but the start. At six feet, five inches, he could get up and running in his first few steps, no wobbling to the side, and stand up and start running in big strides. That’s what its all about. The times that I got the chance to get up, stand up and start running big, that was always great. His consistency where he could get up, start running, get the big wheel is great. So, I had to work on the start so often, over, and over and over again. I can’t even say who gave me technical help with my start. No matter how good technically I’d be in practice, when the gun would go off, I’d have a wobbly first step sometimes. I would have to pull myself together in the first thirty meters. There was a lot of repetition and hard work.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned earlier that you did band training. Did you do much other weight training with free weights or the Universal gym and did you pay attention to your diet and sleep that athletes tend to do more now?

|

| SW |

I was on the beach in San Diego in 1973 and met a gentleman named Bob Clark. He was a vaudeville gymnast. He used to do pushups on one hand. He was a body builder. He saw me on the beach one time and took me to his gym in his garage where he had home made equipment that later wound up being Universal equipment. Bob had to sue the people that mad Universal because they stole his camshaft technology that he hadn’t patented properly. I had Bob giving me specific exercises for each running motion. When I was at San Diego State, they had a pitiful gym and Arnie Robinson hand carried me and taught me explosive lifting. The jumper that he was, he guided me with explosive lifting techniques. Prior to that in El Paso, we had a terrible gym at UTEP. I would go in there after workouts and I would see the incredibly famous Indian triple jumper, Mohinder Gill, working out. He was so skinny, and he was squatting six hundred pounds. I would see guys, particularly the jumpers, who had phenomenal weight-lifting routines that I bought into because I was training for explosive strength and I liked that very much. When I moved to the San Francisco bay area around Stanford, I used to train with the football team. I weighed a hundred and seventy-five pounds and I was half squatting five hundred fifty pounds and benching almost three hundred pounds. I had such a skinny frame that, no matter what I was lifting, I was not getting bigger. I was just staying skin and bones. But I had an incredible strength to weight ratio. I remember one time training with Eric Heiden at Stanford when he was bike riding at that time. Eric Heiden used to go in the gym and grab the whole rack of weights. Even the football players had to step back and say, ‘Let him do it.’ Being inspired by other athletes and being in good gyms was most helpful. Training as they do now with the specificity is amazing. When I was training in the 1970s in Gainesville, we had nothing. But when I was recently at Florida Field in 2015, they had a weight coach for the track team. It’s a phenomenal program. If I had the specific weight training the way the science of the sport has evolved, it would have been amazing. To this day I don’t like vitamins. I don’t like to take pills. I used to try to eat a lot of vitamins back then and I can’t say I even knew what I was doing. I used protein powder and took salt tablets so I wouldn’t get cramps.

|

|

| GCR: |

We talked about some of the great runners you raced against. Did you have any favorite competitors that you enjoyed racing because you looked at them and they looked at you, neither of you were going to back down and you were taking each other to a higher level?

|

| SW |

Unlike longer races, in a sprint there is not a whole lot of thinking in the middle. We’re in a boxing match and the knockout is coming. I liked everybody who was professional. I admired the professionalism of the other athletes that I used to race against and particularly the athletes I trained with. Don Quarrie and I had this mutual professional respect. I would show up to races and didn’t know they invited him. He would show up to races and didn’t know they had invited me. We would look at each other and our gaze said, ‘Okay, let’s go, let’s go.’ I used to love messing with Hasely Crawford. Hasely was a big shit talker. But the last thing you want to do is shit talk with me and get my adrenaline up. That aspect was fun. I have a funny story about a race we ran down in his country of Trinidad in 1975 where we ran a windy 9.8 seconds for the one hundred meters. Three days prior to the meet on the airplane all the Trinidadian athletes were talking badly to me, and some of them were my friends. (Steve starts using an island accent here) ‘Hasely is going to kill you, mon! This is our home5, mon! You’re not going to come here, mon!’ (laughing) Hasely was talking so much stuff. I was in a bar two days before the meet and I’m talking to the bartender. I asked, ‘If you were to insult a Trinidadian guy, what would you call him?’ He said, ‘I would call him a scrunter.’ So, I said in my best Trinidadian accent, ‘A scrunter? What’s a scrunter?’ He told me a scrunter is someone who is trying, but never makes it. I liked that. Two days later, we were getting ready to run, and Hasely was talking stuff. Just as we were taking our sweatpants off and getting into the blocks, I called him a scrunter. (laughing uncontrollably) Oh, he got so upset. He got so shocked. My mother is from the islands so, even though that word was new to me, I knew how to make it sound good. He was so flustered, but it had the opposite effect. He ran like his life depended on it. Twenty yards from the tape I knew I was going to catch him. I caught him at the tape. He had been talking so much stuff that I looked at him at the finish line and the crowd went absolutely berserk. So, some people got my blood boiling and others I was happy to see because of their professionalism.

|

|

| GCR: |

Are there any other races we haven’t discussed that come to mind as memorable races that you would like to share the story?

|

| SW |

A memorable race that has a huge backstory was my second AAU Championship when I ran 9.9 for 100 meters in Los Angeles. I had just lost the NCAAs to Reggie Jones as you mentioned before by a hair and I had lost a race in Modesto on a dirt track to Ivory Crockett who had run nine flat for 100 yards. He out leaned me there in Modesto. I had lost two biggies in a row. Now I’m twenty years old and everybody is ready to dethrone me and throw dirt on the body. He’s done. He’s lost two big races in a row. At the tie I was battling with San Diego State and the coaching staff about me breaking every NCAA rule that was possible in 1974. Prior to the NCAAs, I disappeared for a weekend and flew from Los Angeles to Paris, France for the grand opening of the Adidas boutique. This was when I switched from Puma to Adidas. The picture was in the French newspaper and the NCAA got a hold of it. They asked San Diego State what I was doing in Paris when I was supposed to be in school. So, I had all this drama going on – drama, drama, drama! Finally, the track and field season for college was over and I knew I wasn’t going back to college. Here we are at the AAUs. I left, I disappeared and didn’t train with the San Diego State track team. Coach Hill was looking for me. I went to El Paso and I ran the sand dunes for three days. I came back to Los Angeles and I checked into a hotel – not the dormitory. I stayed hidden until the AAUs and I came out there ready to kill – just ready. I won that race and at the end was looking around and messing around because I was so excited. That was a memorable race. I remember afterward I was in the press area where all the reporters ask questions. I recall sitting there and taking my shoes off and saying to myself, ‘Don’t talk. Don’t say anything. Just sit here and look at the press. Everyone was talking bad about you just last week.’ I sat here and was asked if I was going to say anything. I sat there easily for three minutes and three minutes of silence is a long time. Everyone thought something was wrong with me because I wouldn’t say a word. I was savoring the fact that you better watch out because everyone in the press that loves you when you’re at the top will be trying to tear you down when you’re on the bottom. One other race that is in my thoughts as it deals with being famous, is in 1973 when I won the AAU 100 meters and 200 meters. I was eating in a restaurant the next day and Bill Toomey invited me over to sit at his table. Bill Toomey gave me the greatest advice that you could ever have at nineteen years old. He said, ‘Steve, don’t believe what they write about you in the newspapers, good or bad. If you believe the good, then you’re likely to believe the bad.’ After that, my relationship with the press was cordial, but I realized they weren’t on my side. In 1974, I shut all those mouths at twenty years of age at the AAU National Championship at UCLA.

|

|

| GCR: |

Were there any jobs you had after you retired from running that were exceptionally memorable?

|

| SW |

When I retired from running, I was hired by Moet-Hennessy, oddly enough by 1948 Bronze Medalist in the broad jump, Herb Douglas. For me to get through this conversation and not mention Herb Douglas shows you that my memory is not complete or that I have had too many great men in my life. He is my business guru. I worked for Moet-Hennessy from 1984 to 1988 and then they merged with Louis Vuitton. Herb was my guru and my confidante. He told me, ‘Steve, I know you’re wild and crazy and I know you like to break the rules. But I’ve seen your paperwork.’ He worked me in. Herb also helped with my foundation. I was an account executive for Moet-Hennessy in New York for all the top restaurants and top clubs like Studio 54 and Regine’s. It was an unbelievable retirement job.

|

|

| GCR: |

Steve, as you are in your mid-sixties, what are you doing for health and fitness to keep in shape as you hopefully have a couple decades or more ahead?

|

| SW |

My dad was into physical fitness and he was skiing up to age eighty-five. We had to take his skis from him. When I was a kid my dad wanted me to be a quarterback, to be a black quarterback, so he got me in the back yard and used to make me throw the football. He always played games with me. He’d say, ‘Throw it ten times.’ I’d throw it ten times. Then he’d say, ‘Throw it five more.’ And I’d throw it five more. If I threw sidearm, he would tell me not to and to practice good technique. So, my dad raised me to always try to be in shape. When I retired from running, I started roller blading. I roller bladed as much as forty miles. I loved that sport. It had the same motions as running, you got good cardio and you got to be out and about. My wife is Brazilian, and I used to go down to Copacabana and roller blade for there to Ipanema. I’ve taken my roller blades all over the world. I went from weighing 184 when I retired in 1984 to 200 pounds in about eight weeks it seemed. It didn’t help that I got a job with Moet and Chandon, so I was eating a lot anyway. I try to keep an eye on my diet. When I find a good stationary machine like a step machine, I always put in at least an hour of hard cardio. I do a lot of core work on the stomach. I never was a big meat eater, but I’m having a recent problem during this covid-19 virus that I’m munching too much at night. So, I’ve got a few pounds to work on. I’ve always lived a healthy lifestyle. I don’t drink much. If I’m drinking, I’m having a Guinness which is healthy and fattening at the same time. I’m weighing 225 pounds now and I would like to be at 212 pounds. I’ll get back there.

|

|

| GCR: |

Your hall of fame inductions include the United States National Track and Field Hall of Fame in 2013 and the San Diego State University's HOF 2016. Is it both rewarding and humbling to be so honored after all these years, to go back and make a speech and see old friends?

|

| SW |

Again, we can’t discuss this without a back story. Let’s talk about the U.S. Track and Field Hall of Fame. For the life of me, I never thought I would get there just due to politics. I had broken every NCAA rule. I fought with Ollan Cassell. I fought with the Olympic Committee. I fought at every level and broke every rule so the sport could become opened up like it is today. Most people don’t know all the stuff that I pulled. So, I never, ever thought the U.S. Track and Field federation would honor me knowing that side of it. Brooks Johnson said to me, ‘Steve, I’m going to put in the paperwork for you.’ Probably around 1992, Doc Walker came up to me and said he was going to put I the paperwork for the Hall of Fame. My smartass answer was, ‘Doc, is there any money in it?’ He punched me in the arm and said, ‘No.’ (laughing). But, in 2013 Brooks put the paperwork in. He said, ‘You do this for your family. You don’t do it for yourself.’ It was an honor to be able to share it with my wife who had not been around during my track years, so it was nice. The san Diego back story is even worse. I only ran for San Diego State in 1974. Even though I graduated from San Diego State, I redshirted in 1973 and I only ran for them for one year. And because of all my violations of NCAA laws, the University was fielding all kinds of nonsense because of me. I left the San Diego State track team on a rather shaky level, but I was still going to school there. Some of the University administrators and the track coach banned me from training on their track. They had me removed by the campus police. When a lawyer saw this happening, he put together a case and we sued the University. I sued San Diego State for violation of civil rights because they wouldn’t let me on the track. So, you tend to think you’re not going to be in a Hall of Fame over that. I was faster off the track than on the track because there were so many things going on negotiating with thirty meet promoters over a season, arguing with the shoe companies, social life, and school. I was dodging the AAU on all kind of nonsense, travel permits, did I get money and where my money was. They mistreated Brian Oldfield who threw the World Record in the shot put. He revolutionized the sport where everyone uses the Oldfield spin and they mistreated him over some arcane bullshit amateur rules. All the other people at the top of the AAU were being paid full time. I know so much about what the AAU and TAC were doing and the behind the scenes shenanigans. We could be here all day. In 1980, during the Olympic boycott, a very famous Italian TV Late night star, Johnny Mina, came to me and took me to a famous clothing brand called ‘Ellese.’ He took Edwin Moses, Rod Milburn, Pietro Mennea, and me to be on the Ellese promotional team. The owner of Ellese took us up to his beautiful house in the Torino hills and he proceeds to tell us that he wanted to produce the team uniform for the United States for the next Olympics. We thought that was a big thing to bite off. Then, Mr. Vitale, the head of Ellese, proceeded to create rue du Kappa. In 1984, rue du Kappa winds up making the team uniforms. Edwin Moses and I introduced Ellese to TAC or AAU or which ever one was in charge. The scandal that went on underbrush and behind the scenes with Mr. Vitale using us as his emissaries is hair-raising. The behind the scenes stuff was infinitely more complicated than a nine second race.

|

|

| GCR: |

Have you thought about writing a book that delves deeper into some of the incredible behind the scenes stories?

|

| SW |

I’ve got about twenty-five pages of thoughts just like we have had today. I wouldn’t want to write a normal book. I would want it to be memoirs and I would want it to be like we are doing here with someone asking the questions and me giving the information. I wouldn’t want it to be a narrative of my whole life’s story. I would just want the great track stories because I’ve had some.

|

|

| GCR: |

When you give a minute summary to athletes or youngsters or business groups and you look back at the major lessons you have learned during your life from working to achieve academically and athletically, the discipline of running, racial injustice, and coping with adversity that can help them to succeed, what do you say that sums up the ‘Steve Williams Philosophy’ of striving for your best as an athlete and to be your best in life?

|

| SW |

I’ve taken a spiritual path. In 1975 I got connected with transcendental meditation. I dabbled in it for a while because of my need to quiet my mind. My philosophy is to quiet your mind and to have peaceful, invigorating conversations with your inner self. You must have that relationship with your inner self. If you want to perform in any theater – music, business, sports – you must have very, very compassionate, and confident speaking with yourself. You must believe in yourself. You have to tell yourself, ‘We’re going to do this. We’re going to do that.’ You must pay attention to this world around you and then realize, after you have paid attention, what do you intend to do. If you are a musician, do you intend to be a great musician and do all the things that the great musicians must do. If you intend to be a great businessman, do the things that a businessman has to do. The discipline to do that will give you an extreme, mental inner peace.

|

|

| |

Inside Stuff |

| Hobbies/Interests |

Rollerblading winded up being my preferred sport after track and field. I haven’t been on roller blades for about two years because I’ve been having those testy knee problems for the first time in life. I’m a big music fan. I love my daughters. I take cold dips in Lake Michigan – one of those polar bear things. I like to jump in cold water here in San Francisco. I like the beach. I like spending some time helping youth with youth programs but, with the current health situation, I think everybody in America doesn’t know what to do next

|

| Nicknames |

I used to write ‘Flash’ on my sneakers as a kid, so all my guys know me in New York as ‘The Flash.’ I used to wear The Flash emblem on a couple of my running singlets

|

| Favorite movies |

I remember watching James Bond movies when I was a kid and getting caught up in being that international man of intrigue

|

| Favorite TV shows |

When I was growing up in the Bronx, I was in the street all the time, so I can’t say I had too many favorite television shows as a kid. Nowadays, I like a lot of spy and adventure kind of programming

|

| Favorite music |

Music was so important to me all my life that I got from my parents. It was the Motown era when I was growing up. During my running years I really got into jazz fusion. I happened to have met Stanley Clarke who, by the way, used to be a hurdler. ‘Return to Forever’ and ‘Santana’ were groups I liked. I was a Jimi Hendrix fan since high school. I was excited to listen to certain riffs from high speed fusion songs. Almost, in a strange way, I would use them as a metronome in my head. I listen to a certain section of this song, ‘Return to Forever,’ by Chick Corea, that is called ‘Romantic Warrior.’ There is a series where all the musicians are easily playing as fast as they can humanly possibly play. And they are playing together. I used to have that in my brain as a metronome to try to run as fast as Jimi Hendrix’ hands or as fast as this last piece of music that I heard from a fusion group. So, music has always been important to me. When I’m on the relaxing side, I’m a big reggae fan. I happen to have met Bob Marley in 1980 down at the Hollywood Bowl. Bob had a hold of my hand and he wouldn’t let my hand go because track is that big in Jamaica. He was a fan of mine and that was humbling to me. I was trying to get my hand out of there and he said (in Steve’s best Jamaican accent), 'You are the one who beat Quarrie, mon'

|

| Favorite books |

I remember as a kid I read the Althea Gibson story. In New York, we didn’t have a whole lot of books that were promoting black stars. I was so impressed by Althea Gibson’s story as a child. In college, I can tell you the books that drove me out of my English major – Beowulf and Chaucer. That made me switch to telecommunication my last two years. I read a fair amount of autobiographies and one of my favorites is by Reginald Lewis of Beatrice, called ‘Why Should White Guys have All the Fun?’ I found that to be an invigorating story on how to become a businessman in the merger and acquisitions area where he was involved. I also read spiritual books. I recently read books of Bepop Tchupa. The lesson I discussed with you about attention and intention was one of the lessons from Bepop Tchupa. In the last two years I have been reading less and less books like everyone else and getting caught up on the internet, but when you can read five newspapers on your telephone, it sort of takes over your reading

|

| First car |

My first car was a 1969 Camaro Rally Sport that I got for six hundred dollars. My father had given me a thousand dollars he had saved for me to go to college. I didn’t need the money for college because I was on scholarship. Coach VanDenberg arranged for the bank to sell me the car at a big discount. I was in the car business for a while. I was importing Mercedes out of Europe. In San Diego I worked with an exotic car dealership. In 1976, while the Olympics was going on, I got upset and went and bought me a Mercedes with the money I got from the Puma contract that I didn’t have a chance to cash in. I’ve had four Mercedes in my time and was selling some of them, bringing them into the United States

|

| Current car |

I have a 1998 Mercedes 500 SL, which I rarely drive, and I have a putt-putt Nissan that’s good on gas. If you want to talk about driving, I have a whole set of stories about driving as a black man with a white, convertible Mercedes in San Diego in 1976. I used to get stopped so often that it was incredible

|

| First Job |

My first and only job as a teen was as a messenger for a stationary company. I used to deliver packages. They used to give me bus fare to deliver the packages. Instead, I would run there, or I would walk fast and pocket the money

|

| Family |

My mother passed away a couple years ago when she was 92. My dad is still alive and will be 96 this December. I was raised in a middle-class home. I was two hundred yards away from very rough housing projects in the Bronx. I was raised in a very loving home. When I was born, I was extremely pigeon toed and they had to pull me out of mom. When I was three months old, they had to break my legs and reset my feet in a cast. I also had asthma. My mother would cry when she walked down the street because people would say she was a bad mother since she let the baby break both his legs. After that, maybe at nine months old, they took off the cast, I stood up and started running. My mother always used to make jokes, ‘If it weren’t for me, you wouldn’t be able to run straight down the lane.’ I was raised very well. My parents were incredibly supportive. My dad was a very spiritual guy and still is. My sisters and brothers weren’t into athletics. They had their own interests. I have two sisters and one brother. When I talk to my daughters, I am very much the coach. ‘You can do it. You can do it.’ Everything they want to do, I support. I told them there was no one better than them. I support them in female liberation and to not take any crap from any men. My oldest daughter is a lawyer and my youngest daughter is in her second year of university. My daughters are Jade and Jeannette. My wife is Flavia, and my wife is the sweetest, loving person I have ever met. I’ve been all over the world and in 2002 we met, and we have been together ever since. We go back every now and then to Brazil to see her family. I never thought I could settle down. When I was doing my speech for the Hall of Fame at the U.S. Track and Field Federation, she was sitting in the audience and I had said to the attendees, ‘No matter how fast you think you are, love will catch you'

|

| Pets |

We have had no pets. My family wasn’t the type that had pets as they were just trying to feed us and didn’t want extra mouths in the house

|

| Favorite breakfast |

I have never been a breakfast guy. I used to drink my breakfast and still do. I like a smoothie with everything possible in it. During my running career, I would drink a smoothie in the morning

|

| Favorite meal |

A very-well cooked salmon, a nice wine, a beautiful tossed Caesar salad and then I’ll ruin all that healthy food and eat a bunch of cake afterward

|

| Favorite beverages |

Red wine, Guinness, and Champagne. I’m a Champagne guy and I have a collection of Champagne glasses from all over the world. One of my after-work out drinks was Guinness, an egg, some honey, and condensed milk in a blender. When I was in London, I was told that doctors would prescribe what I just said for pregnant women because of the nutritional boost that combination would give. That was one of my elixirs

|

| First running memories |

Running with Mr. Magliarity, ‘Mr. M.,’ was my earliest running memory of competing in an organized fashion. They lined us up and had us run across the park which was about forty or fifty yards. Mr. Maliarity just told me to make sure none of the kids were in front of me in the end. That served as my mantra through my whole running career. I was always fast. If we were playing touch football, I was the one who would go long. If we were playing tag, I was the last one to get caught. There were two girls on my block who were faster than me. One of the girls who was faster than me, she was so fast her name was ‘Bullet’ and she used to run circles around me. And, I remember the policeman, Mr. Clark, when I was eleven or twelve years old, saying, ‘I think you can do this’ when he saw me run. Those are my earliest memories

|

| Running heroes |

I vaguely remember Bob Hayes in the 1964 Olympics. My dad was a big football fan and was telling me about this track guy who was also on the football field. He was one of my earliest heroes. When I saw the way Bob ran, I never thought I could be a one-hundred-meter runner because I was so skinny, and Bob was so powerful. Bob was so powerful that I thought I should find something that the skinny guys could do. I remember in 1968 watching Tommie Smith and he was so skinny that I thought, ‘If he can do it, I can do it.’ And, for some reason, I knew I was always going to be political because of Tommy. Mel Pender is my heart. I love Mel. He is one of the guys I came across from 1968 and all the way up to Carl Lewis and Ben Johnson that I knew. My breadth of experience covers a lot of ground

|

| Greatest running moments |

When I ran 9.4 in the Junior Olympics in Glen Cove, New York. At the time, when I was in high school, I was primarily a 200-meter and 400-meter guy. I had only run the hundred one previous time and ran under a friend of mine’s name, Derrick Skipper. I was supposed to run the two hundred and got up there and decided to run the one hundred, so I ran under Derick’s name. I won my heat and got second in the final at 9.6 seconds. That was the only hundred I ran in high school. When the Junior Olympics came up and I ran 9.4 seconds, that was the first time I had this out-of-body experience in the hundred. That was the epic deal for me. In 1972, we had a meet against USC and Brigham Young in El Paso. USC came with Don Quarrie and Lance Babb and Benny Brown and Willie Deckard. They came down there and thought they were hot stuff. They thought they were too hot and too tough. I won the hundred and the two hundred. I ran a leg on the relay and USC ran a phenomenal race to win that. The race was kind of defining to me that I could run with the big guys. The final big races are my comebacks. In 1974 when I came back and ran 9.9. In 1977 when I came back and won the World Cup and we set the World Record in the relay. Those are the races that are the most memorable to me

|

| Worst running moments |

Without question, in 1976 when I pulled up in the AAU meet. I have to say that in 1972 I had run 44.9 and I got hurt the next day. There was the fact that I was on a breakthrough moment in the 400 meters and got hurt and had to start all over again. Either one of those injuries, but 1976 was worse as there was so much publicity and I had achieved so much before the injury. Yes, those were dark moments. I never thought when I got hurt in 1976 that I thought I would not be back. There was not one moment that I didn’t think I couldn’t beat everybody I had beaten before. When I talk about those instances, there was an inner confidence that carried me through some very tough times

|

| Childhood dreams |

I wanted to be an astronaut. It looked like the thing to do. I kept all the newspaper clippings from the astronauts, and I wanted to be an astronaut

|

| Embarrassing moment |

I’m always being a clown. I do stuff that my daughters are complaining about like clipping toenails

|

| Unusual moment |

When I got hurt in 1976, I immediately rushed to San Diego. Then I rushed to New York to do the Today Show with Dick Schaap two days after I got hurt. They sent a limousine to take me downtown and I felt like I was in a hearse. I was stretched out and felt like I was in a back seat of a hearse. Then I was walking the streets and I would have so many different responses. Some people would say, ‘You’re a bad so and so’ and I would say, ‘Thank you.’ The next person would see me and say, ‘I’m sorry you got hurt.’ This was because CBS had taped the Martin Luther King Games two weeks before the Trials and had held onto the broadcast. They competed with the Olympic Trials, which were on NBC, by showing the Martin Luther King Games. On one day you would see my getting hurt and on the next day see me run a World Record because I ran a 9.9 one hundred meters against Harvey Glance that day. Just to walk and have that experience made 1976 a helluva story

|

| Favorite places to travel |

When I stopped racing and retired, I had been to forty-four countries. I kept going. I’m going here. I’m going there. My favorite spot in the world was Brazil. I love Brazil. I was down in Brazil in 1981 the first time and was at a hotel on Copacabana with Puma representatives. They were telling me that Pele was getting ready to show up at the hotel. When he did, it almost caused a riot. I went twice to Thailand. One time I lived in an air-conditioned hut on an island of Thailand for about five weeks and Thailand is paradise. So, Brazil on one side of the world and Thailand on the other

|

|

|

|

|

|

|