|

|

|

garycohenrunning.com

garycohenrunning.com

be healthy • get more fit • race faster

| |

|

"All in a Day’s Run" is for competitive runners,

fitness enthusiasts and anyone who needs a "spark" to get healthier by increasing exercise and eating more nutritionally.

Click here for more info or to order

This is what the running elite has to say about "All in a Day's Run":

"Gary's experiences and thoughts are very entertaining, all levels of

runners can relate to them."

Brian Sell — 2008 U.S. Olympic Marathoner

"Each of Gary's essays is a short read with great information on training,

racing and nutrition."

Dave McGillivray — Boston Marathon Race Director

|

|

|

|

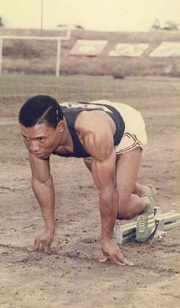

Mel Pender ran the second leg on the 4 x 100-meter relay at the 1968 Olympic Games where he and his teammates earned the Gold Medal in a World Record time of 38.24 seconds. He also competed in the 100 meters at the 1964 and 1968 Olympics, finishing seventh and sixth, respectively. Pender set World Records in the 50-yard dash at 5.0, 60 yards at 5.8 and 70 yards at 6.8 seconds. While preparing for both Olympic Games, Mel was a U.S. Army Officer in combat in Vietnam who was recalled stateside to train for the Olympics. During his military service, he won six CISM Championships which are affectionately known as the ‘Military Olympics.’ He retired from the Army after 21 years, earning a Bronze Star and rising to the rank of Captain. Amazingly, Pender did not compete in track and field until age twenty-five. His personal best times are: 100 yards – 9.3 and 100 meters – 10.15. He earned a bachelor's degree from Adelphi University. Mel owned an Athletic Attic store in Atlanta, developed a track shoe for Mitre, organized the Muhammad Ali Track Club, worked with the NFLPA Youth Development Camp, and served as Director of Community Affairs for the Atlanta Hawks Foundation. He has been inducted into eleven Halls of Fame including the Adelphi University HOF, Georgia Military Veterans HOF, Georgia State Sport HOF, Bob Hayes HOF, Atlanta Sports HOF, Louisiana HOF, Bellsouth Spirit of Legends HOF, and Officer Candidate HOF. Mel and his wife, Debbie, reside in Marietta, Georgia with their dog, Paco.

|

|

| GCR: |

It is hard to fathom that it has been over 50 years since you won a Gold Medal as a member of the 4 x 100-meter relay team at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. If you close your eyes does it seem like a long time ago and, at the same time, just like yesterday?

|

| MP |

I can picture it like it was just yesterday because of the 100 meters and how I ran, because I was leading the race for about seventy meters and I don’t know what happened.

|

|

| GCR: |

It is tough when you are leading in the 100-meter open event before falling behind, but you were able to come back in the relay and be part of a foursome that won the Gold Medal. Sometimes people focus on individual accomplishments, but how nice was it to share that Gold Medal with three teammates?

|

| MP |

It was special, and especially at my age. I was 31 years old and the oldest guy on the team. I didn’t run competitively until I was 25 years old, as you know from reading my book, and to make two Olympic teams after being pulled out of Army service in Vietnam both times, didn’t give me much time to get ready for both teams and to compete.

|

|

| GCR: |

The Olympic Games have grown in stature, visibility, and commercialism considerably since 1968. How big of an achievement was it amongst your family, friends, colleagues in the Army and community to not only make the Olympic team, but to win a Gold Medal?

|

| MP |

It was a big deal for me because I grew up in a poor neighborhood. It made me like a superstar in my neighborhood. To my parents and my grandparents and all my friends I was a hero. When I won that Gold Medal, I had been pulled out of Vietnam and I did not want to go. I did not want to leave my men. I trained with them and was responsible for their lives and I promised them I would win a Gold Medal for them. I begged the Colonel not to send me, but he had no control over that and the military leadership in Washington sent me.

|

|

| GCR: |

Your 4 x 100-meter relay team had not won all its races leading to the Olympics and many didn’t think would win. What strategy did your coach, you and your relay teammates implement, both mentally and physically, in training and on race day to put you in position to challenge for the victory and take home the Gold?

|

| MP |

We were like brothers – four peas in a pod. We weren’t like the relay teams after 1968 that had mainly individuals and prima donnas. We also had a great coach in Stan Wright. Charlie Greene was hurt. They wanted to replace Charlie and we said, ‘No!’ And Charlie didn’t want to be replaced either. We stayed together with Charlie. If you saw one of us, you saw the other three guys. We worked hard on it, every day, twice a day. Sometimes at night we would jog around the track and pass the baton and make sure we got the handoffs. It was something we wanted so badly. I knew it was probably my last Olympics because of my age. The other guys probably could have gone on for the 1972 Olympics, which they didn’t, and I did. I wanted it so much and had worked so hard after being in combat in Vietnam. To come back from the jungle in Vietnam when they pulled me out and to win this medal is something I can’t explain. I was in Vietnam for six months and they pulled me out. At the 1964 Olympics I was 27 years old and in 1968 I was 31 and knew that, if I was going to win an Olympic medal, I had to win it then.

|

|

| GCR: |

Charlie Greene passed the baton to you a bit behind, you took the lead, Ronnie Ray Smith held it and Jim Hines took it home. Can you describe the race – getting ready to take the baton, sprinting down the back stretch, handing off and the emotions as your teammates held the lead and you were part of a Gold Medal foursome?

|

| MP |

I was initially supposed to be the leadoff man, but Coach Stan Wright said I was a better straightaway runner than a curve runner. When Charlie got hurt, we had to adjust our steps and I had to move mine up a bit to exchange the baton in the international zone. When Charlie got to me, he was a little behind. We had a great handoff and I made up the stagger. I ran up on Ronnie Ray Smith and was on his back a little bit. He didn’t take off fast enough. Ronnie got the baton and he was behind when he handed it off to Jim Hines. If it wasn’t for Jim Hines on that anchor leg, I don’t think we would have won that relay.

|

|

| GCR: |

What was it like on the victory stand, receiving your medals and hearing the National Anthem, especially in light of what Tommie Smith and John Carlos had done on the podium when they made their protest for humanitarian reasons earlier in the Games? As both a soldier and an athlete representing the country, can you tell us about those moments?

|

| MP |

As a military man since I was seventeen years old, it was a great feeling for me. It was and then it wasn’t because I grew up in the south. Imagine growing up in the south in the 1950s and 1960s and the things I had to endure. I was called names because I was black, and we were mistreated back then. There were black and white water fountains. I had to ride in the back of the bus because I was black. I couldn’t go to some restaurants. At the theater I went up front to get movie tickets, then had to go through an alley and up two flights of stairs to get to the balcony to watch the movie. I’ve always been very sensitive since I was growing up as a kid. But when I stood up on the victory stand, after what John Carlos and Tommie Smith did, I had a mixed feeling. When I had just come back from Vietnam, and had taken my mom to the doctor, we went to the doctor’s office and had to go in the back door. There were two chairs and a small table. I went up front and asked the receptionist why we were in the back. She said, ‘That’s where ya’ll supposed to sit.’ I emphasize that she said, ‘Ya’ll.’ A lot of things went through my mind in those moments. I had just come back from Vietnam and watched young men die. When John Carlos and Tommie Smith did what they did, I was called in by my Colonel because he thought I was involved in the demonstration. I said to him, ‘What color is my skin? I’m a black American. Because of what I’ve been through in my life, I have mixed feelings about what just happened with John Carlos and Tommie Smith. But, as a military man, in the United States Army, I can’t get involved in any demonstrations because I have a Captain’s bar on my shoulder, and I represent my country.’ He said, ‘you know you’re supposed to go to flight school when you return to the United States.’ They had done some research on me. I didn’t get to go to flight school when I got back. They screwed me out of that for some reason. When I stood on that victory stand, I thought about my men in Vietnam. I don’t know why that came up, but their faces came up and I had tears in my eyes. I said to myself, ‘I accomplished my mission.’

|

|

| GCR: |

We appreciate your service and we appreciate your representing our country in the Olympics despite all the racial prejudice you had to endure throughout your life. You mentioned about what John Carlos and Tommie Smith did on the podium at their medal ceremony. Since John was your roommate at the Olympics, can you relate about his emotions and any conversations you had back in your room before his expulsion from the Olympic Village and some general commentary about race in America?

|

| MP |

He was my roommate, but I didn’t know that John was going to do what he did. He never mentioned what he and Tommie were going to do. I was one of the spokesmen, Ralph Boston and me, because we were the oldest guys there. We said to our teammates, ‘If you have it in your heart to do something on the victory stand or on the track, no one is asking you to – it’s up to you. Everybody did their own form of statement that most people didn’t recognize – black socks, black shoes, buttons. A lot of the guys and girls on the team did things that weren’t very noticeable. I didn’t see John anymore because he was staying mostly in an apartment with his wife like all the married guys were. John came back to our room and got his stuff and I didn’t even know he was gone. I thought he had just left the Olympic Village, but he and his wife were gone. Afterward, I talked to John and congratulated him. John lives here in Atlanta too and is like my brother. He is my hero. What John and Tommie did on that victory stand took a lot of nerve and a lot of heart and they were punished for it. They were saying that ‘I am a man. My skin color may be a different color, but we should not be treated differently. We are Americans and live in the greatest country in the world.’ Even today after over two hundred years, black people are treated differently because of the color of our skin. You can’t totally understand what I’m saying because I’m a black man and you’re not black. There were the things I’ve been through during my life growing up in the south and in the military where I was treated in ways that I shouldn’t have been treated. There were all the heroic things I had done and how I represented my country and the flag and National Anthem. I am patriotic and I believe in my country. I persevered onward. But I am still an American and a black man in the United States of America. A lot of my friends didn’t come home because they were killed in combat. Those who did were treated differently. They couldn’t get a job and were still treated like second class citizens. They weren’t treated like Americans, but like animals. There were so many black Americans who died for this country in the first World War and second World War. My father was in the Navy in World War II and he couldn’t get a decent job after the war in the little town of Dothan, Georgia, where he was from. I saw my daddy sit down and cry because he couldn’t get a job and earn enough money to support his family after he served this country in the second World War. There a lot of things that brought pain and suffering to my friends and to me as a black man. I served my country for twenty-one years in the military, in two Olympic Games, got a Bronze Star in Vietnam, earned a Gold Medal, was inducted into eleven halls of fame – why?! Why?!

|

|

| GCR: |

It is a sad reflection on our country. We have ups and downs in race relations in this country but, fortunately for me, as a child in Miami I lived in a diverse neighborhood. I participated on the track and field team, which was mainly black athletes, except for the distance runners and some weight men who were white. I was exposed to black athletes and camaraderie and those kinds of times together have helped us in our country as we have moved two generations since then. The more we experience togetherness, I feel the more we emphasize our similarities rather than our differences and it has been like that for me. Do you have any thoughts on this?

|

| MP |

First, I did meet a guy from Miami, Gerald Tinker, who was on the Olympic team in 1972. His cousin, Larry Black, was also on the four by one-hundred-meter team that won the Gold Medal. But I want to get back a bit more to John and Tommie and what they did on the victory stand. It wasn’t a black power salute. The newspapers blew it up like that, but it wasn’t about black power. They were saying that we were black and proud, we were from America and were representing their country and why were we being treated differently? Why couldn’t we be treated the same? Black athletes were winning most of the Gold Medals in track and field. We were representing our country and why should we be treated any differently? If we weren’t winning the sprints and other races and events we won, the United States wouldn’t have won the Olympic Games. Without the black athletes on the Olympic team, the United States would never win the Olympic Games. The 1968 United States track and field team was the greatest Olympic team in the history of track and field and there will probably never be another team like our team. And to go through what we had to go through. We never got to go to the White House. When I came back from Vietnam, I was called a ‘baby killer’ when I was wearing my uniform. If you were in my place, how would you feel? Today, people are marching. People all over the world are seeing the light – the way that blacks are treated in America. People are tired of what is happening, and they know it isn’t right the way young black men are being killed today. This is the greatest country in the world, and we should never have these instances going on. The light is shining on race and segregation in America. We have to get rid of the President we have because he makes the problem worse. This man is the most racist president we have ever had in the United States. I’ve never seen anything like this. What this man is doing to this country is pitiful. People around the world see it and they are talking about it. This makes us look so bad with him doing what he is doing to our country. It’s a shame. It’s a disgrace.

|

|

| GCR: |

This fall we may have a change there, so we will see. I am hopeful that the effects of the covid-19 pandemic will ease, and sporting activities will resume this fall. Sports bring people together and we tend to minimize our differences, such as skin color, nationality, sexual preference, gender and root for our team and our athletes.

|

| MP |

We are hopeful. I’m 82 years old and will be 83 in October. I know my time is getting short but, hopefully in my lifetime, my grandchildren and my great-grandchildren won’t have to go through what black people have gone through in the past two hundred years. I pray that there is a new picture of what America is supposed to be like. This country is made up of people from every nation in the world. People came here from all over the world to make this country what it is today.

|

|

| GCR: |

That is true as my family came mainly from Poland in the early 1900s. Some were Catholic. Some were Jewish. Some of my Jewish relatives who didn’t come to the U.S. were killed during World War II in the holocaust. We all have stories behind us in terms of what happened and lots of things were terrible.

|

| MP |

Yes, they are terrible. But if we had a leader that cared about all people in America, we would not be in the position we are today. How can people support a man who is like that? It hurts me because of what I have seen. My grandfather used to tell me about things he went through back in the 1920s. My father died over fifty years ago, and he and my grandfather told me stories about what they went through when they were growing up. This is why I am the person I am today - because I listened. I was told that I had to be the best I could be, and he told me why – it was because of the color of my skin. I was told that I would always be looked down upon and to get a good education and do a lot of reading. I used to read all the time. You have read my book and how I got my degree when I was traveling sixty miles to Adelphi University from West Point. I didn’t mean to get off point, but this is important.

|

|

| GCR: |

Yes, this is important and thank you for this meandering. Now let’s jump back into your Olympic Games exploits. In 1968 before the relay you mentioned that, when you toed the line for the 100-meter finals, you lead for two thirds of the race until fading to fifth place as Jimmy Hines won. Can you take us through that race and how your expectations and hopes and dreams compared to the reality of that ten seconds?

|

| MP |

I don’t know to this day. You would be surprised how many times I have gone over that race. I was out of the blocks because I had the fastest start in the world. The first fifty or sixty meters I was always going to be out there. I just had to maintain my distance at sixty meters to get to the finish line of the one hundred meters because I’m short. Even today I don’t know what happened to me. I go over it all the time. Was I straining? Was I afraid I was out too far? Maybe I choked up because I could hear somebody next to me. So many things have gone through my mind. I had beaten a lot of those guys before that race. It’s amazing because of the guys who beat me, I had beat them all. When you’re in a race like that in the Olympic Games or in any race, things happen. You’re a runner and you know that sometimes things happened, and you don’t realize what it was. I was in one of the greatest shapes of my life. Even though I was 31 years old, I had been beating everybody. I won the first indoor meet that year against the Russians in the sixty-yard dash and a question was asked of my coach as to how strong I looked and how fast I was running. I can’t tell you what happened in that Olympic race. I’ve gone over it in my mind a hundred times. If I could do it over again, would it be different. I was glad that I was able to come back because I thought my running was over at the 1964 Olympics at my age. But, to come back and win that Gold Medal, I promised my mother, I promised my guys in Vietnam and my grandparents. And God gave me the strength to come back and win that Gold Medal. It meant a lot to me.

|

|

| GCR: |

Since the 1968 Olympic Games was your second Olympics, how exciting was it to make your first Olympic team in 1964, to know you were an Olympian and you were on to Tokyo?

|

| MP |

I didn’t run until I was twenty-five years old and didn’t know I could be a track runner. One day I was playing football in Okinawa, the track coach saw me, and he wanted me to race against the Japanese team that was training for the 1964 Olympic Games in Okinawa. I asked the coach what he was talking about. When I went to high school, we didn’t have a field or a gym. We had a made-up football team. But he said, ‘Don’t worry, Mel. You can beat them. Go pick up some track supplies.’ I got some shoes and a singlet, and I beat the best runner from Japan that was going to run in the Olympics in Tokyo. There were probably half of the island’s population there – maybe eight thousand people watching. You couldn’t find a place to sit down because so many people came to watch the races. When I did that, there were schools talking to me like Southern Cal, UCLA, Washington State and other schools that wanted me to get out of the Army and go to college and run track. I didn’t do it because I didn’t think I was smart enough to go to college. I reenlisted in the Army and was sent to the 101st Airborne Division. Then I was sent to Korea and read about the Army track team and that’s how I got on the Army track team. That’s how I got my start toward that 1964 Olympic team with teammates like ‘Bullet Bob’ Hayes. The first time I ran against Bob I was like a kid in a candy store. I ran my first USA track and field championship, which was the AAUs at St. Louis, Missouri on a track that was asphalt. It was sticking to our shoes and the asphalt was coming up on our spikes because it was so hot. I didn’t even get to the finals, but I promised myself that I was going to come back the next season and be one of the greatest sprinters in America, which I did. I broke Bob Hayes’ record indoors in the 50-yard dash, at sixty yards and at seventy yards. I ran ten flat for one hundred meters. I had made up my mind to prove to myself, not to other people, but to me, that I could be one of the best sprinters in America. And God gave me that opportunity to do that.

|

|

| GCR: |

What is the story about you getting injured in Tokyo and how you had to persevere to even make the 100-meter final?

|

| MP |

In 1964 I pulled a muscle in the quarterfinals. What really happened is that Trent Jackson and I were horsing around in our room and he punched me in the stomach. It hurt awfully bad. I thought it was just a little stitch, but he had torn the muscle in my rib cage. I went out the next day and got through the heats and the quarterfinals. When I went out for the semifinals, during the race I felt something kind of tear and I barely got through the semifinals. That is when I went to the doctor and he said I had torn muscles in my ribcage. I could not stand him to touch me on my right side. He told me that he could give me some injections to ease the pain, but not along my stomach, only along my back. He said that near my stomach would cause internal bleeding. I saw John Pennel, the pole vaulter, who had also strained a muscle, and the doctor was giving John injections. He gave me a couple injections, taped me up and strapped me up and said, ‘Okay, Mel, it’s up to you.’ Unbelievably, Bob Hayes came up to me, and he always called me ‘Shorty.’ Bob said, ‘Shorty, just watch my behind. Stay on my behind.’ I said, ‘You’re going to be on my behind.’ We were kidding. About sixty or seventy meters down the track all hell broke loose, and I don’t know how I maintained form in the final. After the race I collapsed. They took me to the hospital where they took x-rays and they told me I had some internal bleeding from the muscle I tore along my ribcage near my stomach. I was there for two days and then I came back to the dorm. I got to see a few other races, but that was it.

|

|

| GCR: |

How disappointing was it to be replaced on the 4 by 100-meter relay due to the injury and to not have a shot at the relay Gold Medal?

|

| MP |

It was very disappointing. Also, some things happened there that most people don’t know. Gugenback was the coach and he wanted his guy on the relay team. He wanted to replace Trent Jackson or me so that he could get his guy on the team. We protested because that guy had never beat any of us in the 100 meters and there was no reason to replace one of us. But Trent Jackson strained a muscle and I got hurt, so it put his guy on the relay on the third leg. Paul Drayton took my place on the leadoff leg. There weren’t alternates like there are today. If someone was hurt, the replacement was a 200-meter runner. Gerry Ashworth ran the second leg, then Richard Stebbins ran the third and Bob Hayes anchored. You don’t know how badly that hurt. At my age I thought it was probably over for me in track. That’s why I started working more on my career and I went to Officer’s Candidate school and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. I was sent to Vietnam and they pulled me out after six months to train for the 1968 Olympics. I was supposed to go to flight school after the Olympics. But when I got back, somebody pulled a fast one on me because I had taken all the tests – flight tests, written tests, physical tests – everything, and I passed them all, but there was no flight school for me. They wanted to send me back to Vietnam in two weeks, but I refused to go and somehow someone in Washington got me delayed six months and sent to Fort Bragg for six months. Then they sent me to Vietnam again in the 82nd Airborne Division. I stayed there for nine months and then they pulled me out to train for the 1972 Games where I would have been 35 years old.

|

|

| GCR: |

You had a shot at making a third Olympic team in 1972 at age 35 but strained a calf muscle twelve days before the Olympic Trials and didn’t make the team. How disappointing was this?

|

| MP |

I would have made that team. I was running very well. I could have made the relay team. I was beating almost all the guys on that relay team – Gerald Tinker and Ray Robinson and the rest. I pulled a muscle at the AAU Championships at the University of Washington in Seattle. When I got to the Olympic Trials, I couldn’t get through the quarterfinals and that was the end of my career in track. Though I did run professionally for three years.

|

|

| GCR: |

A final Olympic question - what are some memories from both Tokyo in 1964 and Mexico City in 1968 that stand out as to Opening and Closing Ceremonies, watching amazing track performances or attending other sporting events?

|

| MP |

In 1964 it was Billy Mills’ race. We became good friends. He was a Marine. That was amazing what he did. I was in the stands for that. In 1968 it was Bob Beamon’s long jump. It was unbelievable. This guy was soaring like a bird in the air. You would not believe how he was flying in the air to jump twenty-nine feet. He was amazing and it was amazing to see that. It was also amazing to see Wyomia Tyus in the 100 meters. The track in 1968 was a rubberized track while in 1964 it was like cinder mud. In 1968 there were so many amazing events won by athletes, not only from the United States, but from other countries. But seeing what Bob Beamon did and how Billy Mills came back from way behind to win that race were unbelievable.

|

|

| GCR: |

What was it like in 1968 training in the beautiful nature setting of Lake Tahoe with Charlie Greene, a good friend, to make the team, and to have camaraderie that we haven’t seen before or since then?

|

| MP |

That was amazing. We were a family. Black and white athletes, we were like brothers up there. To be so close together, living in trailers, brought us closer together. It was something how close we got. Even today, we are still close. The athletes from 1968 at Tahoe – we are still brothers. We still get together, especially here in Atlanta with Tommie Smith and John Carlos and some of the other athletes. We have got together for trips and cruises. We talk about the desire to go back up to Tahoe for another reunion. That is going to happen because Ed Caruthers’ brother, Sam Caruthers, is dying from cancer. We all said that we want to go back to celebrate his wedding because that is where he got married. I talked to Ron Whitney yesterday. He was a distance runner. As an aside, he just read my book and laughed, ‘I didn’t know your name was Melvin!’ But he asked me to please let him know when we make plans for a reunion because we were a family. Tahoe had an unbelievable track where we couldn’t see the runners when they went around the curve because of the trees. It was beautiful. We had great coaches. The camaraderie was unbelievable. We were always joking. At night we would get together and go to the casinos and hang out and have dinner. Bill Cosby did a show for us and invited all the Olympians. It was amazing to be at Tahoe. I want to go back as soon as possible because I don’t know how long I’m going to be here.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned how you didn’t start running track races until you were twenty-five years old. Most Olympic track and field athletes start in high school or earlier and then compete in college as they develop their talents. How much did it help you in 1962 when Coach Cornell Lipscomb, the track coach at Fort Hood, worked with you?

|

| MP |

Coach Lipscomb made me who I am today in track. If not for Coach Lipscomb, I would not be a Gold Medal winner. I would not be a World Record Holder. When I went to Fort Hood, the two top sprinters on that team were John Moon, who is still coaching at Seton Hall, and Bobby Poynter, who went to San Jose State. They were both great starters and they taught me everything I know about starting. They used to make fun of me because of the running outfit I had and the old Army shoes I had. I didn’t know what track shoes even looked like. Coach Lipscomb gave me some Adidas shoes to wear and some uniforms and I thought I was in another world. Coach Lipscomb was a conditioner too because he was a Colonel in the Army. He was not only a coach, but a conditioner. He taught me how to run the proper way instead of sitting in the saddle with my head up and leaning back. He would have me walk around the track at nighttime leaning forward. If he caught me doing other than what he taught me to do, he would have me run a fast three hundred meters. And I hate running three-hundreds all out. I could have killed him (laughing), but I loved him too because of what he did for me.

|

|

| GCR: |

After running your first races that were outside the United States, what were your first races on U.S. soil?

|

| MP |

My first race back in the States was when I ran against North Carolina Central. Doctor Leroy Walker was their track coach and I ran against his guys – Edward Roberts, Norman Tate – they had a great team back then. I was stationed at Fort Bragg and drove up and beat his runners. He tried to get me out of the Army to run on his team. My second race was at Morgan State College. That’s when I met Alex Woodley. I beat their best sprinters who were from New York and Philadelphia. I ran 9.5 for 100 yards on a cinder track. After the race Alex asked me if I would run for him and the Philadelphia Pioneers. I remember taking a bus from Fayetteville, North Carolina to Baltimore, Maryland and one white guy was with me that ran track. His name was Chappell and I didn’t know he was going to be there. He was also in the 82nd Airborne, but I didn’t know he ran track. He ran the distance races. When I got there, I didn’t know where to go and didn’t have the address. I went to this black hotel near Morgan State when I got there in the evening. I had worn my military uniform there but, in the morning, changed into my sweats. On our way back, Chappell and I hooked up and took the Greyhound bus back to Fayetteville. We stopped to get a hamburger at this diner next to the bus station in Baltimore, Maryland. Chappell walked in first. I walked in behind. Then a lady came up and said, ‘You can’t come in here.’ I couldn’t come in because I was black. That was in 1963, because I came back in 1962, ran my first U.S. track meet in 1963 and made the Olympic team in 1964. Chappell got angry and he told this white lady off. I cried. It hurt me so badly. I turned around and walked out. He was still in there raising hell with the lady. Chappell came out and asked if anything was the matter and I said, ‘Nothing.’ It hurt me so bad, and I was dressed sharp. We wore khakis back then – khaki shirts and khaki shorts and I had my 82nd Airborne symbol on my hat. I was always dressed sharp with my clothes starched down and she said, ‘He can’t come in here.’ That made me very, very, very angry. I didn’t want to let anything get to me like that again. I was going to persevere and ignore it and be the best I could be. I decided I was going to show them. I remember saying to myself, ‘I’m going to be the best at everything.’ And in 1964 I made the Olympic team.

|

|

| GCR: |

How did joining the Philadelphia Pioneers Track Club and racing all over the U.S. and Canada turn you into an experienced racer who was ready for a variety of racing surfaces, weather conditions and competitors and what did Coach Alex Woodley do to help you as an athlete?

|

| MP |

When I went to run for the Pioneers and Alex, I was already a great runner by then. Alex got me in meets around the country. Alex could get money to get us to go on trips. There was a guy that worked for the Ford dealership named Burt Lancaster in Germantown, Pennsylvania who helped. Sometimes we would have to hustle money to go on trips and Alex was like a father to us, getting us money so we could have food and a hotel to stay in. We were already in shape, so he didn’t to coach us too much. He did coach us, but most of us had already been coached. He did set up the workouts for us and give us pointers if he saw us doing something wrong.

|

|

| GCR: |

I would like to expand a bit more on your going back and forth from Olympic athlete to soldier. We read about the chronology, but what was it like emotionally going from Olympic athlete in 1964 to combat soldier in the jungles of Vietnam and back to Olympic athlete in 1968? What was it like to try and make the switch while both facets of your being were going on at the same time?

|

| MP |

I was a soldier first and I was an athlete second. I had my duties to perform and I had men that I had to lead to keep them alive. The military came first. I was always a sharp dresser. I was sharp in everything I did – in maneuvers and in training my men – that came first. I was an athlete at night. At maybe nine o’clock at night I was on the track. I’m training to that level until 10:30 or eleven o’clock at night. The next morning I’m up at five o’clock being a soldier first. That’s what I had to do, and most people don’t know I did all that. I had my wife and family with me. Being an athlete and a soldier wasn’t easy, but the people that know me know that I get the job done no matter what it takes. I had to do that with my men because in combat you can get yourself killed, get your men killed, and you don’t want to do that. One of the most hurting things that every happened to me was seeing one of my men get killed in Vietnam.

|

|

| GCR: |

That reminds me of when I hear words like ‘a soldier may leave the war, but the war never leaves the soldier behind.’ How did that Vietnam War change you and stay with you for the rest of your life?

|

| MP |

It never leaves you, just like you said. I have post-traumatic stress. I’ve had seven operations, cancer, leukemia for which I just got out of the hospital a few months ago and I’m getting chemotherapy. There is pain we go through. Every day I’m in pain. It reminds you of the war and reminds you of being a soldier. I will always be a soldier. I am a soldier. If they call me back, I’m a solider today first because I love my country.

|

|

| GCR: |

You joined the Army at a young age and had a lot of other responsibilities as you had gotten married, had a child and were still a teenager. How did growing up faster than your peers and taking on the responsibilities of manhood cause you to jump ahead of many of your friends to face adult life?

|

| MP |

I was married at age sixteen and joined the Army at seventeen because I had a responsibility to my family. When I joined the Army, it was something I had always dreamed of since I saw the movie with Audie Murphy, ‘To Hell and Back.’ My father was in the Navy and, living in the environment I was living in, that was the only way out for me. I couldn’t go to college and didn’t think I was smart enough. I had a family first and, being black, what kind of job could I get? I was digging foundations for homes and driving trucks, working at drug stores and service stations. I didn’t want to do that. How was I going to support my family making that little money so that they would have a decent life? I did travel to the golf course to work as a caddy and I walked through these beautiful subdivisions to get to the Capital City Country Club, which was the most beautiful country club in Atlanta. It was about two miles that I had to walk. As I walked through these beautiful neighborhoods, I saw these beautiful homes and their cars and their families and their children and I thought that someday I wanted to live like this. And I never gave up on that. It was always my dream and my goal and my hope that one day I could have a decent life like these white people were living. I never gave up. I kept pushing forward.

|

|

| GCR: |

When you were even younger you had challenges, especially with moves from Georgia to Chicago and back, your parents getting divorced when you were young, and the increased influence of your grandparents. How did your childhood and adolescence develop you into the young man that you became?

|

| MP |

There were the things I saw around me, the things my grandfather would tell me and the talks he gave me about life. My father wasn’t there. My grandfather would tell me things about life. I used to shine shoes at Buckhead in Atlanta. I was a shoeshine boy. I didn’t want to do that, but I had to support that wife I had and our little girl. That is why at seventeen I joined the Army. My dreams were to be better than that. I didn’t want to live the rest of my life like some of the boys and young men in my neighborhood were living. They didn’t work. They didn’t take care of their families. They would have babies and wouldn’t take care of them. That was not me because my father wasn’t there for me and I didn’t want my family to live like I did and my daughter to not have a father there for her. It made me strong. I said, ‘I’m going to do this and be the best that I can be.’ When I was in the military, from the beginning in basic training, I was the best on the physical test in my whole battalion. I set records on the P.T., not knowing I was going to do so. It was just me. I did not know I had that ability. The military gave me that opportunity to be the person I am today. Listening to my grandfather’s talks about life and seeing the young black men in my neighborhood getting beat up by the police during the day and not having jobs, not supporting their family, not making enough money to take care of their family and having babies and not taking care of them wasn’t me. Since my father wasn’t there for me, I wasn’t going to let my child grow up that way. Listening to my grandfather and seeing what was going on around me led me to do the things I did to be the best that I could be and made me the person I am today.

|

|

| GCR: |

Though you didn’t run organized track meets until you were twenty-five years old, in which sports did you participate as a youth and teenager and were you always one of the fast runners?

|

| MP |

Let me tell you something. When I was living in Dothan, Georgia we had a nice school. It wasn’t integrated, but it was a brick building with central heating and radiators in the rooms. When my mother and father got divorced, we moved to Atlanta, actually Decatur, in Dekalb County. We had to take taxis to school about six miles away. They didn’t even give us a bus. They finally built us a school in my community called Lynwood Park, a little cinder block building with fourteen rooms, concrete floors, and no central heating. There was a little pot-belly stove with a stove pipe under the widow panes, no running water, and an outdoor toilet maybe fifty meters from the school. That is the kind of school I had to go to. But we had great teachers and a principal. We had a makeshift football team. We even had some guy that didn’t come to school who came and played on our football team. He was a bigger guy. That gave us hope. That gave us feeling that we had something and that somebody cared about us enough for us to show our talents that we didn’t even know we had. I didn’t know that either. When I was running with the football, I would get the ball and I would make a touchdown. I didn’t know I was that fast. The principal we had named Elly Robinson was like a father to everyone in that school and the teachers were like mothers to the kids in the neighborhood. The community of Lynwood Park was over two hundred years old and the land was given to the community by a slave owner. In my book you see a picture of the little red building, which was the schoolhouse building when it first started out. Our football team practiced on rocks. We didn’t have any grass. I was red clay and rocks that we played on. We didn’t have much, but we had people that loved us. We had people that cared about us. And we had teachers that cared about us. I had one year to graduate when my high school sweetheart became pregnant. Back then students couldn’t go to school when they were pregnant. I went up to New York for six months and they told me that I wasn’t qualified up there to go to the twelfth grade and would have to stay in eleventh grade. They were more advanced in New York than we were in Georgia. I went back, my principal let me go to summer school and then let me come back to school in the fall. I was captain of the football team, had good grades and a good family. I was there one more year and graduated. I did all kinds of work then to take care of my family – digging foundations, pushing wheelbarrows to finish basements. I did everything I could to be a good father and a good husband to my young wife at age sixteen.

|

|

| GCR: |

We have touched on mainly your Olympic racing and a few other select races. Are there two or three other races that stand out as great races due to you beating a particularly tough opponent, coming from behind or for setting records?

|

| MP |

When I went to Australia, I won the Australian Championships with a strained muscle in my leg. I won four races in Australia with a hamstring muscle that was not pulled, but it was sore. I also won at the first Russian-USA indoor meet in Richmond, Virginia after coming back from the jungles of Vietnam. That was in 1970. The day after that I broke the World Record in the 50-yard dash in Hamilton, Ontario. Other memorable races are that I won six CISM Championships which are the military Olympics where all runners in the military from all over the world would come together. Some of those guys were on the Olympic teams for their countries. For me to beat those guys and to be number one at CISM was big. Winning the 1964 Inner Service championships at Quantico, Virginia is how I automatically qualified for the Olympic Trials. When I set the World Record in the 60-yard dash at 5.8 seconds on the pro circuit was one of my most rewarding races as was when I broke Bob Hayes’ record in the 70-yard dash. I still hold the records in the 50, 60 and 70-yard dashes because they don’t run them anymore. There are races I remember where my goal was to beat Charlie Greene or Jim Hines. That was my goal. I beat both after the Olympics. There were some races where I was in the lead and somehow, they would get me right at the end. We are still friends, but Charlie Greene is in bad shape. He is in a nursing home, but we talk once a week.

|

|

| GCR: |

When I interviewed Billy Mills, he spoke of how he raced Tunisia’s Mohammed Gammoudi at CISM in 1963, they became friends and then Billy outkicked him to win the Olympic 10,000-meter Gold Medal in 1964. Did you make any friends with athletes from other countries in a similar fashion at CISM that you have remained in contact with over the years?

|

| MP |

Not really. I have kept friendships with mostly American athletes. At CISM there isn’t much time. You’re there and you’re gone. It’s two or three days and you’re gone. There is a guy from Japan that I beat in Okinawa who was in my qualifying races the next year in Tokyo, but he didn’t qualify for the final.

|

|

| GCR: |

After your competitive days you were assistant track coach at Army, but didn’t get the head track coach job when the Coach Crowl passed away from a heart attack because they didn’t think West Point was ready for a black head coach. How disappointing was this?

|

| MP |

I didn’t get that job because of the color of my skin. At my last birthday party at age 82 there were twenty-five of my cadets who I coached at West Point that came from all over the country because they believed in me and I changed their lives. They weren’t just black athletes. White athletes came too. Things happened to me as a black man. That tore me apart and I never could get over that and some other things that happened to me in my lifetime. I guess when you get to my age in the eighties you can find yourself going back to the past and wondering why something happened. The word ‘why’ always comes up. My book is called ‘The Expression of Hope’ because I was always hoping that things would be different, and I would be treated equal to the white man in this country. Why did we have to be treated differently because of the color of our skin?

|

|

| GCR: |

After you stopped racing, how rewarding was it to stay involved in the sport of running through the Athletic Attic store in Atlanta, developing a shoe for Mitre and the Muhammad Ali Track Club?

|

| MP |

I got the franchise for Athletic Attic from Marty Liquori and I wanted to get the top twelve girls in Atlanta, the top sprinters and runners, and start a track club. I designed that shoe for Mitre which was mainly a soccer ball company, one of the tops in the world. They asked me to design a shoe and we called it the ‘Mexico.’ I set a World Record in them in Madison Square Garden. We took the girls all over the country to run in indoor meets in California and New York and all over. We had shoes and designed uniforms and it was beautiful for these girls. They never would have had a chance to do that. Muhammad Ali came to some of the meets and the girls were excited to have his name attached to the track team. When we went to Los Angeles, it was the girls first time on an airplane. One of the girls was supposed to go to Tennessee State, but she went to Alabama and I still am in contact with her. My wife is a minister and married her and her husband.

|

|

| GCR: |

You stayed around the sports arena as you worked with the NFLPA Youth Development Camp and as Director of Community Affairs for the Atlanta Hawks Foundation. How did serving your community in the football and basketball community along with many community boards and associations expand and broaden your horizon and round you out?

|

| MP |

It was a time where I continued working with kids with the NFLPA camps in the summer. I trained kids in track, which I still do today with my cousin and my great-granddaughter. I try to stay involved with young people because they need help, especially young athletes. I am a multi-task person and I love kids. I got to talk about how I grew up and the things I was faced with. My goal was to help kids to do better and to persevere and to be productive in their lives. There are lot of ‘kids having kids,’ like me. I was a kid having a kid when I got married and there are so many of those. I try to help those kids with no fathers and young mothers who have no time because they are so busy with a baby and trying to make a living. I would have speaking engagements with kids and their parents. I always want to better the lives of young people, not only black kids, but white kids, red kids, it doesn’t matter – we’re Americans. They could become the president or the mayor of their town. What happened with the NFLPA camp is there are kids who had professional athletes as counselors and now some have master’s degrees. There were athletes from many sports – football, basketball, track – it was one of the best programs this country could have for the kids and disadvantaged youth. I still have my scrapbooks and it was an unbelievable program. That was also when I had my store. I was doing so many things including going around the country with the Jobs Corps Center. The head of that group heard me speaking and asked me to work with them. I have always been an active person and have wanted to help people. I love people.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned your book a few times, ‘Expression of Hope: The Mel Pender Story,’ which you wrote with your wife, Debbie. I enjoyed the book and am looking at it now. I may go back and read it again and it has some great pictures. If people would like to order your book, or find out more information from your website, what is best to do?

|

| MP |

Just go to www.melpender.com to order the book from there. It is also on Amazon. From what I understand, it is also at Walmart.

|

|

| GCR: |

As I noted, you wrote your book with Debbie. Over the course of your adult life you have had several marriages. How much of a blessing has it been to find Debbie and to share your ‘golden years’ with her?

|

| MP |

Let me tell you, she is my angel. After I got my last divorce, I felt it was over for me in marriage. The way we met is a great story and I have to tell you how I met her. I was at church one Sunday and I didn’t go to the main service. I spoke to the youth service that morning. As church was letting out the Minister stopped me and said, ‘I want you to meet somebody.’ I didn’t know it was Debbie. What had happened was that the drummer in the church band, who was former Mayor Maynard Jackson’s son, was a very good friend of Debbie’s son. The son came and brought her with him. She had just got back from being in England for three years and doing some missionary work in Africa dealing with clean water. At the same time, I had a company in Lesotho in South Africa for the World Cup Soccer. She asked if I had welding equipment and I told her I didn’t but had equipment that could purify water. I gave her my business card and she called me a couple days later. She said, ‘I’d like to meet with you and talk about Africa,’ so I met her. That was it! One year later after the date we met, I married her. She has been a blessing in my life. She took care of my mother until she passed away at 96. I don’t know what I would have done because I had moved my mother in with me when she got older. Debbie has been with me through four or five operations, holding my hand during the pain. She has been right there like an angel. That is why I say she’s my angel. She is the one who said we should write my book. It took four or five years to write it while we were taking care of my mom and her mom in Minnesota and Debbie worked on her degree in psychology. It has been a long road, but God was right there with us.

|

|

| GCR: |

You have mentioned having several operations and cancer. How is your current health, and what do you do for health and fitness?

|

| MP |

I don’t look 82. I don’t talk 82. I don’t walk like I’m 82. I play golf as much as I can. Of course, I’m in pain for two days after I play golf. I have nerve pain in my right side. I can’t be still. My wife gets on me all the time. I do things around the house to keep busy. Like I said, I’m a multi-task person. My wife has me drinking a lot of water. If you want a glass of water, ask me and I can bring it right out. I was in the hospital a few weeks ago because I had an episode where I passed out from being dehydrated.

|

|

| GCR: |

What tips would you give youngsters starting out in athletics, particularly running, that would serve them well in their pursuit of excellence and help them to stay fit throughout their lives which is a troubling aspect of American society?

|

| MP |

The first thing I tell kids is to listen. My grandpa used to tell me, ‘Listen, listen.’ Kids don’t listen to their coaches, don’t listen to their parents, don’t listen to their teachers. They are out there doing their own thing. If they want to be successful in life, they have to listen first. They also must set goals for themselves. That’s what I did. I looked at me and what I had to do. I set goals and I had to be determined to reach those goals. I had to be productive in everything I did. I tell kids to listen to people who are older like parents and teachers. A lot of young people don’t do that. A lot of young black kids I know, young boys, figure there is nothing out there for them. In other words, there is no future for them. They aren’t even getting a decent meal. Some don’t get a good night’s sleep. Then they get involved with these gangs and they care more for the gang members then for their parents. They think these people are their family. I talk to them about all of that and about drugs. All I can do is tell them how I feel, what I went through and the things that made me who I am. That’s what I try to tell them.

|

|

| GCR: |

After everything you did in athletics and in the military, how rewarding and humbling has it been to be honored by induction into at least eleven halls of fame including the Adelphi University HOF, Georgia Military Veterans HOF, Georgia State Sport HOF, Bob Hayes HOF, Atlanta Sports HOF, Louisiana HOF, Bellsouth Spirit of Legends HOF and Officer Candidate HOF?

|

| MP |

The Officer Candidate Hall of Fame is one I am particularly proud of as that was not easy. I think about my mother and my grandparents. I never forget when they came to my graduation from Officer Candidate School. When I walked across the stage, my grandmother jumped up – she’s something else – and said, ‘That’s my boy!’ I was so embarrassed that I didn’t know what to do. But afterward the General wanted to find my grandmother and me and to thank her for getting up and saying that. No one ever got up and did that before. ‘That’s my boy!’ And it got quiet after that. That was very special to me to get into the OCS Hall of Fame because not that many get into it. I am proud of who I am and the goals that I set. All these things made me feel like I accomplished my goals that I set as a kid after everything I saw when I was growing up.

|

|

| GCR: |

When you look at life as a whole and the lessons you’ve learned – whether it’s athletically, academically, the discipline of studying, the responsibilities of Army life and marriage, balancing the many components of life and recovering from adversity you have faced, how is that summed up at age 82 as the ‘Mel Pender Philosophy’ of being your best in life?

|

| MP |

I sum it up this way. God gave me a gift. God helped me to accomplish my goals that I set when I was a kid. God gave me the ability to be one of the fastest runners in the world. Without him in my life, I would not be talking to you right now. God gave me the opportunity to come out of the jungles of Vietnam and to compete in track and field when so many of my buddies didn’t come home. I do believe that without faith and hope that all the things that I have done would never have happened without believing in Jesus Christ, our savior. I know for a fact that coming out of Vietnam was God’s doing. I thank him and the people who helped me along the way like my coaches. I feel like I accomplished my mission. As they say in the military – I accomplished my mission. Being the person that I am and being able to do all the things I have done and, even the life I have today with a beautiful wife and all the dreams that I ever had after being married several times, he sent me the right person, the right woman, to make my life complete. That is how I sum it up.

|

|

| |

Inside Stuff |

| Hobbies/Interests |

Golf, fishing, and shopping. My wife knows that, and you can’t imagine - I’m a man that likes to go out and spend money. I buy a lot of her clothes. And I like to gamble. I play blackjack

|

| Nicknames |

My nickname was ‘Charlie.’ And they called me ‘Charlie Chan’ because I was bowlegged like the oriental guy. Some people called me ‘Junior,’ which I hated. My name is Melvin Pender, Junior, but I never use it

|

| Favorite movies |

‘Audie Murphy – To Hell and Back’ is my favorite movie

|

| Favorite TV shows |

We watch game shows like ‘Wheel of Fortune.’ I love ‘Wheel of Fortune.’ We also watch ‘Jeopardy’ every day at dinner and we watch ‘Family Feud.’ I like action movies like those with Sylvester Stallone. I used to not be able to watch movies about Vietnam, but lately I am able to watch them. They bring a lot of memories back but now I’m able to look at some

|

| Favorite music |

Charlie Wilson is my favorite musician. I love jazz. I also like Christian music

|

| Favorite books |

I like action books. I’ve been reading books by people that participated in athletics by John Carlos, Tommie Smith, and Wyomia Tyus

|

| Favorite comedian |

Do you remember George Wallace, the comedian? He grew up in my neighborhood, Lynwood Park. His brother taught me how to play golf. They are great golfers. He is the greatest comedian in the world. My wife is reading his book right now and will just start laughing when she is reading in bed. George Wallace can tell the funniest jokes and he is so real

|

| First car |

I have had thirty cars. My first was a 1940 Ford coupe

|

| Current car |

It is a Fisker Karma. It was first made in Finland. Now they make it in California. My last car before that was a Corvette

|

| First Jobs |

My first job was as a caddy when I was fourteen. When I got to be fifteen, I started construction work building foundations for houses. This black guy had a company. Then I drove for a drug store delivering pharmacy items. I delivered flowers for a florist. I worked in a gas station fixing tires and serving customers back in the days when we pumped gas for customers. They didn’t pump their own gas back then. I shined shoes. That was one of the most degrading jobs I had. I didn’t like it, but I had to have money. I heard about the job and I did it

|

| Family |

I have three children. I have the girl who I had when I was sixteen who is now sixty-five years old. I have a son who is forty-one. The third is 39 years old, going on forty. My mother was a beautiful woman. I loved my dad too. When he came back from the Navy, he had post-traumatic stress which wasn’t heard of back then. He was an alcoholic. I lived with my grandparents from when I was in the seventh grade until the time I graduated and went in the military. I had one sister and she died. She had diabetes. She was one year older than me. My wife, Debbie, like I said, is my angel. God sent her to me. I always dreamed of having a marriage like we have now. We have a beautiful home. We live a decent life that I dreamed of. We each have three children as she was married before and has two girls and a boy. We have a big house. We just moved into a fifty-five and over gated community and we love it. We had a home that was too huge at seven thousand square feet and our new home is thirty-two hundred square feet. It is two levels. I have a man cave upstairs, but I don’t go up there that much. God has really blessed us to live the way we live, and I thank him every day. Looking back on my life with the things I had to go through when I was growing up was not that good

|

| Pets |

We have a dog named ‘Paco.’ He is a terrier. I think he is possessed. He always wants you to play with him. If someone comes to the front door, he is our security system. He runs around the place barking and lets us know.

|

| Favorite breakfast |

I like scrambled eggs, sausage, biscuits, and grits

|

| Favorite meal |

My favorite meal is lambchops and asparagus

|

| Favorite beverages |

I like Coke and Orange Crush, but I don’t drink them anymore. I drink water. My wife just put another bottle of water in front of me. I may have Ginger Ale every once in a while, but mainly water. And I love milk

|

| First running memory |

I never ran at school. I would just run against guys when we were playing, and I would always beat them. In football I was running when I got the ball and scoring touchdowns

|

| Running heroes |

Bob Hayes, Wyomia Tyus, Billy Mills. Charlie Greene, who is like a brother to me. Jim Ryun. Edwin Moses

|

| Greatest running moments |

Setting the World Records in the 50, 60 and 70-yard dashes. When I set the World Record in the 50 yard dash at Hamilton, Ontario and when I beat the Russians – I tell you – those were great moments in my life

|

| Worst running moments |

In the 1964 Olympics and the 1968 Olympics in the 100 meters

|

| Childhood dreams |

Audie Murphy. I wanted to be in the military and win the Medal of Honor

|

| Funny memories |

Ask John Carlos and you will get funny stories. He told me the story about a chicken that knew how to count. That was funny

|

| Favorite places to travel |

I like Italy and I love France. I went to the World Championships in France. I like the Bahamas and those islands. We talked a few years ago about buying a place there. I really like the people there. I’ve been to a lot of the islands

|

|

|

|

|

|

|