|

|

|

garycohenrunning.com

garycohenrunning.com

be healthy • get more fit • race faster

| |

|

"All in a Day’s Run" is for competitive runners,

fitness enthusiasts and anyone who needs a "spark" to get healthier by increasing exercise and eating more nutritionally.

Click here for more info or to order

This is what the running elite has to say about "All in a Day's Run":

"Gary's experiences and thoughts are very entertaining, all levels of

runners can relate to them."

Brian Sell — 2008 U.S. Olympic Marathoner

"Each of Gary's essays is a short read with great information on training,

racing and nutrition."

Dave McGillivray — Boston Marathon Race Director

|

|

|

|

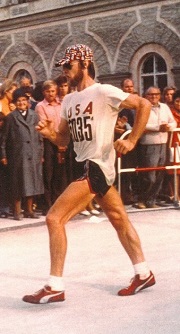

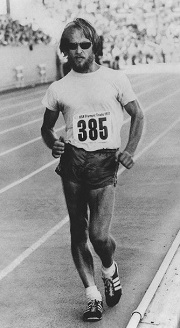

Larry Young won Bronze Medals in the 1968 and 1972 Olympic 50-kilometer race walk and is the only U.S. athlete to ever earn an Olympic medal in race walking. He also qualified for the Olympic 20k race walk in 1968 and 1972, giving up his spot in 1968 and finishing in tenth place in 1972. At the 1968 Olympic Trials, Larry was third at 20k while winning the 50k race walk. In 1972 he won both the Olympic Trials 20k and 50k. He was also the 1967 and 1971 Pan American Games champion at 50k and represented the U.S. in international competition eight times. The winner of 30 national titles, Larry won eight U.S. crowns at 50 kilometers and never lost a championship race at that distance. In 1972 alone, he won eight national titles at various distances from two miles to 100 miles. Young’s 100-mile American Record time of 18:07:12 was set in the University of Missouri’s Fieldhouse on an eight-laps-per-mile dirt track. Larry race walked collegiately for Columbia (Missouri) College. At Fort Osage High School he ran the mile and half mile with best times of 4:48 and 2:10. His known personal best race walk times include: 2-miles - 13:49.5; 5k – 21:39.8; 10k – 44:51; 15k – 1:10:21.8; 20k – 1:30:11; 25k – 1:57:28; 30k – 2:25:26; 35k – 2:52:41; 40k – 3:29:18; 50k – 4:00:46 and 100 miles – 18:07:12. Young’s Hall of Fame inductions include the USATF HOF in 2002, Columbia College HOF in 2004, Fort Osage High School HOF in 2012 and Missouri Sports HOF in 2015. He also was named to Xerox’s U.S. Track and Field’s Century of Champions and Runner’s World’s All-Time U.S. Olympic Dream Team. Larry is a full-time artist who has placed over 50 monumental sculptures in the U.S and internationally. He resides in Columbia, Missouri with his wife, Dr. Candy Cartwright Young. They have two children. Larry was kind to spend over an hour and a half on the telephone in late 2018.

|

|

| GCR: |

Since this past year we celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games, how memorable has it been to see the focus on that Olympiad, the 50-year reunions and camaraderie between the athletes?

|

| LY |

It’s been amazing. We had the full Olympic team reunion in Colorado Springs the weekend of November 26th. Tom Worrell, who was a pentathlete, is the guy who has kind of kept the whole 1968 U.S. team together. We’ve had several reunions over the years. The first one I remember was in 2008 and then we’ve had them every four years during the Olympic years, and then this year. So, Tom Worrell is the one who gets the credit for keeping this team together. There are others involved in keeping us connected. Five of the six walkers from the 1968 Olympic team were at the reunion and we had a fun time getting together. We got on the phone and called Dave Romansky as he couldn’t come because his health isn’t that great. Then on the first of December we went to Columbus, Ohio where the USA Track and Field organization had just the track and field medal winners of the 1968 Olympic team for a reunion. So, it has been quite the year.

|

|

| GCR: |

When we discuss your accolades in Olympic competition, with Bronze medals in the 1968 and 1972 Olympic 50-kilometer race walk, you are the only USA athlete to medal in long distance race walking. Some other U.S. athletes were the only Olympic Gold Medalists in their events such as Horace Ashenfelter in the steeplechase in 1952 and Billy Mills and Bob Schul in the 10k and 5k in 1964. What are your thoughts on this distinction as being the only U.S. athlete to medal in race walking and that no one else has in the fifty years since then?

|

| LY |

It’s kind of surprising and I don’t really have a good answer for that. Here in the United States, especially when I was race walking, there was very little emphasis on the sport. It was not a part of the high school track and field program. It was only an AAU event. Kids in high school were not exposed to the sport. I got exposed to it in 1960 when I was running track and field in high school. I was a miler and half-miler. In 1960, which was two years before I graduated, I saw Don Thompson of Great Britain win the 50 kilometer walk in the 1960 Olympics on television. That was my first exposure to the sport, but I never really got a chance to try it until I got out of the Navy four years later and moved to Los Angeles where I got involved in some track and field all-comers meets at several high schools on different nights of the week. There was always a one-mile walk. I ran the mile and the half mile, and I got into the walk. That’s kind of where I got my first taste of race walking. The United States hasn’t ever focused on it. Now we do have a training center in Colorado Springs and there are race walkers training there. I’m not up to snuff as to our prospects, but for some reason we’ve never been able to get somebody even close in the Olympics. Curt Clausen got a Bronze medal in a World Championships and he has come the closest to an Olympic medal of any U.S. athlete since my days.

|

|

| GCR: |

When we speak about Olympics and World Championships, it must be exciting to represent the U.S. in international competition, which you did at least eight times. How cool is it to put on the USA jersey and how neat was it the first time?

|

| LY |

It’s always exciting. That was my big dream – to make the Olympic team. I got involved in the sport not quite three years before the Olympics. I only had two years of serious race walking in 1966 and 1967 before the 1968 Olympics and was new to the sport. I wasn’t expected to place well in Mexico, but I had hopes that I would do well, get a medal and maybe just win the whole thing. You never know. You just step up to the line. It was an incredible experience. I knew that I had a shot of making the Olympic team because I had won the 1966 National Championships 50 kilometers in Chicago. It was at Horner Park I believe. That was my first National Championship win after winning a Junior National Championship at 35 kilometers. The 1967 National Championships was in Chicago on that same course at Horner Park and qualified me for the Pan Am Games in 1967. That win gave me the opportunity for my first international competition in Winnipeg, Canada.

|

|

| GCR: |

We will speak a bit more about those Pan Am Games, but first going back to 1968, to compete in the Olympics you first must make the team. You competed in the Olympic Trials 20k walk and 50k walk and the 20k came first before the 50k which was your strong point. Since you never are guaranteed anything in racing, when you came in third in the 20k walk behind Ron Laird and Rudy Haluza, how exciting was it to know that you were on the Olympic team even if you had an off day in the 50k?

|

| LY |

It was very comforting. I went into the 50k three days later feeling comfortable.

|

|

| GCR: |

In the 1968 Olympic Trials 50k you won by over ten minutes ahead of Goetz Klopfer. How did the race develop, when did you pull away, how far into the race did you feel you were going to win and what was the effect of the altitude?

|

| LY |

I have a vague recollection of the race and the course. I was pretty much out in the lead the whole time and was never threatened or challenged. It was a pretty easy day for me and kind of left me in limbo. There was no one in this country who could challenge me. It left me thinking of what my chances were in Mexico City. The altitude training certainly helped me. There is no doubt about that. There were a bunch of guys who went to Mexico City from Europe that never had a chance to do any altitude training and I felt sorry for them. A lot of them didn’t really have an idea of how the altitude would affect them over a long distance. Christopher Hohne of East Germany, who won the Olympic 50k in Mexico City, had the World Record in around four hours and ten minutes going into that race. My best time was around 4:20 at sea level. I knew I would be about ten minutes off my best time due to the high altitude.

|

|

| GCR: |

Before the Olympic Trials at altitude in Alamosa, there were low altitude Olympic Trials. What is your recollection of that racing experience in the context of making the 1968 Olympic team?

|

| LY |

At the low altitude Olympic Trials there was a 20k held in Long Beach, California and a 50k in San Francisco. They told us that if we won either of those races that we were automatically on the Olympic team. They were going to take ten guys from those races for high altitude training. The 20k was a hard-fast race and I had the dang thing won. Ron Laird was behind me and I had maybe twenty yards on him. He wasn’t that far back, but I knew that I was going to win the race because I only had maybe a quarter of a mile to go. I don’t know if it was the excitement of making the Olympic team or what, but I started throwing up. I was puking. Ron loves to tell this story and says, ‘I had let you go, and I knew you were going to win the race. But I saw this green stuff flying over your shoulder and you were slowing down.’ Well, when you’re puking, you can’t hardly do anything. So, I’m bent over puking and he goes by me. He just walked by me. I managed to regroup and got second place, a few seconds behind Ron. There went my berth in the twenty kilometers. Two weeks later we went up to Golden Gate Park in San Francisco for the 50k low altitude Olympic Trials and there I just wiped the field out. So, then I was on the Olympic team. Next, we went to Echo Summit Training Center near Lake Tahoe and at some point, in time the U.S. Olympic Committee put out the word that the low altitude Olympic Trials did not count. Now they told us that whoever finished in the top three at high altitude would go to the Olympics. They pulled the switcheroo on us. I had to remake the team and was the favorite in the race. I wasn’t too concerned and knew that if I didn’t have a blowup or bad day that I was going to be okay. I was disappointed in my high altitude 20k, but I did finish third and made the team.

|

|

| GCR: |

Why did you skip the 20k in the Olympics?

|

| LY |

I decided not to race the 20k in Mexico City because I was still green in the sport and didn’t feel that the three days between the 20k and the 50k were enough. I felt that I should focus on the 50k, which was my best shot, and not expose myself only three days beforehand. So that moved Tom Dooley onto the team in the 20k.

|

|

| GCR: |

So, the Olympic 50k had the dual challenges of high altitude and hot weather and several of your competitors still went out fast while you took a more conservative and steadier pace. Can you take us through the race, where you stood halfway through and when you picked off enough other walkers to move into third place?

|

| LY |

Let’s start at the beginning. Paul Nihill of Great Britain, who had won the Olympic Silver Medal in 1964 behind Abdon Pamich of Italy, was considered one of the two favorites in Mexico City along with Christoph Hohne. I had walked against Paul Nihill in a 20-miler quite a bit earlier that year, or the year before, over in England. He won the race and he finished second – he beat me pretty good – so I knew this guy was a real threat. He had walked the second fastest time ever. That morning of the race I was sitting there having breakfast in the Olympic training center with Paul Nihill. He and I were friends and had gotten to know each other. I asked him, ‘Hey Paul, how fast do you think this race is going to go?’ And he said, ‘I think it’s going to be between Christoph Hohne and me and it’s probably going to go in about four hours and ten minutes.’ I knew and he knew that that was the World Record at sea level – four hours and ten minutes by Christoph Hohne. I said, ‘okay Paul, you walk your 4:10 pace and I’ll see you around 35 kilometers.’ I kind of laughed and he laughed at the funny joke. Well, sure enough, somewhere in the neighborhood of 35 kilometers here was Paul Nihill just absolutely staggering along the road. They ended up taking him to the hospital with severe heat exhaustion issues like a lot of people. A question I wonder is how many people in that race ended up in the hospital? There were a bunch that did not finish, but I don’t know how many ended up having to have medical care (note – seven of the 36 who started the race did not finish). When I went out of the stadium, I was dead last. I was race number 32 and was the last one out of the stadium. I can tell you that because my dad took video of the race. It isn’t a great video because my dad was new to the Super 8 camera and there was a lot of jiggling and taking video into the sun. So, there is trouble seeing sometimes. But to have the record is great. Midway through the race I had worked my way up about midway through the field. I was walking my pace and walking my race. That was my plan and not to get out of control by trying to stay up with the leaders. I knew that I hadn’t been in the sport that long and that there were a lot of people up there who had walked faster times than me. I just gradually started picking people up and it was amazing. By 40 kilometers I found myself in third place. I had passed the East German, a guy by the name of Peter Seltzer, who was in third place. So, I put myself in third place and I could see Antal Kiss of Hungary up ahead. I was gaining on him and kept gaining on him, but I just didn’t have enough to catch him and to nail second place. Christoph Hohne just wiped the field out and won by ten minutes.

|

|

| GCR: |

When you came into the stadium, how many laps did you have to walk and when did you know that if you didn’t cramp or have a health issue you had a medal?

|

| LY |

I knew I had a medal when I went down into the stadium. All they did was bring us into the stadium and down the ramp and then about three quarters of a lap all the way around and to the finish. And so, I knew that I had third place wrapped up. Of course, the crowd went nuts. There were a lot of Americans down there.

|

|

| GCR: |

What was the feeling like when you were on the medal stand and to see the USA flag up there in Bronze Medal position for you and then to receive your medal as an Olympic Bronze Medalist?

|

| LY |

That was just awesome. What more can I say? It was awesome!

|

|

| GCR: |

Did you have any trouble with the food and water in Mexico City or did you confine yourself to the Olympic Village food?

|

| LY |

I didn’t sample the local food with bad effects, but at least two of my teammates did. Ron Laird finished third in the World Championships 20k in East Germany in 1967 and we all thought he would win a medal, and possibly Gold, in the 1968 Olympics. He was ready for it. He’d established himself as one of the top walkers in the world. He went down to Mexico City and what does he do? He goes into town and eats the food and drinks the water and gets terrible diarrhea during the 20k race. That also happened to Dave Romansky in the 50k.

|

|

| GCR: |

Continuing along with your Olympic participation, let’s jump forward to 1972 before we return to discuss some racing in between your two Olympic Games. In 1972 you won the 20k and 50k events at the Olympic Trials and seemed to be much more experienced and coming into your own. How did you feel going into the 1972 Olympic Trials and during those races as you won the 20k by a couple minutes and the 50k by seven minutes?

|

| LY |

I had trained my butt off. I was averaging about a hundred miles a week for over a year before the 1972 Trials. There was a guy out there named Bob Kitchen who was probably my biggest threat in the 50k. He had set the American Record earlier in the year. He was supposed to be my big threat, but I don’t know if he just had a bad day, as he was never in the game. He didn’t even finish in the money. They were both easy races for me. I had no competition either way.

|

|

| GCR: |

When you got to Munich for the Olympics you competed in both events and got tenth in the 20k before you repeated your Bronze Medal performance in the 50k. What was your thought process about competing in both events?

|

| LY |

Let me take you through it a little bit. First, I had made the decision early on that If I won both Olympic Trial races in the 20k and the 50k that I would race in both. It wasn’t because I felt I had a real medal shot in the 20k. I didn’t because there were so many guys in the world that were walking faster times in the 20k than I was. But I had learned from a guy who was a sports physiologist, Ben Landerae, who was a distance runner about this new theory. I don’t know if he came up with it or where it came from, but it wasn’t common knowledge back then. It was called the overcompensation theory. The way it worked was that the idea was to go out three to four days before your big race to deplete as much of the glycogen in your muscles as possible. Then the lactic acid builds up in your muscles and the idea is for the next three days after that hard performance to rest, go slow, stay loose and to focus on eating carbohydrates to put the sugar back into your system to break down into glycogen. This supposedly takes your glycogen up above your normal levels and, at that point in time, you’re ready for your race. I used that and think it worked for me with the 20k depleting me before rebuilding for the 50k. How do you know if something really works? All I know is that I had the best race of my life. I started that race and I was back again.

|

|

| GCR: |

How strong were you feeling as in the 50k you were only two minutes out of the Silver Medal spot and four minutes behind the Gold Medalist? How close were you to moving up to a different color of medal or was it just too tough to beat Bern Kannenberg and Veniamin Soldatenko?

|

| LY |

I didn’t go out with the leaders. I had a comfortable pace and gradually built it throughout the race. My dad was there again taking the video and he also had a stopwatch on him. As the race progressed, from 20 kilometers onward, he was giving my splits between me and the leaders. I was gaining on them and steadily gaining on everybody, not just on the guys who were coming back to me. I was gaining on the leaders. Dad said, ‘You’re gaining on them every lap.’ In the marathon and distance walks, every five kilometers there is an aid station. Each competitor turns in his drinks the day before and it goes in a designated bottle with your number on it. As you come up to the drink stand, they push the drink out to you. Everything went fine. What I drank, and there is some debate as to whether this was wise, was de-fizzed Pepsi. I took all the fizz out of it and that had been my drink for a couple of years. I had experimented around and that seemed to work the best for me. It got my liquid in me, got my water in me, got me a little buzz and it tasted good. That’s what I had in my bottle. When I came up to 35 kilometers I had been steadily gaining and had worked my way into third place. I grabbed my drink at 35 kilometers and didn’t look at the number or the bottle. It was the one the guy pushed out to me and I figured it was mine. I took a swig and it just about made me puke. I threw it down and had to go a whole 5k more without anything to drink. I got about two kilometers in past that and started getting a buzzy feeling in my fingers and a buzzy feeling in my lips and I was thinking, ‘Oh my God, I’m hitting the wall.’ I managed to get back to forty kilometers and had fallen off the pace some. I wish I knew who was on that table. I’d like to have a talk with him today. But I got my regular drink at forty kilometers and I managed to hang onto third place. But who knows what would have happened or could have happened. I was feeling good and so strong.

|

|

| GCR: |

Let’s go back and talk about the Pan Am Games where you had two successful races. Before the 1968 Olympics, as you said, you pulled on that USA jersey for the 1967 Pan Am Games up in Winnipeg, Canada. You won by a large margin as your 4:26:26 time was nearly ten minutes ahead of Canada’s Felix Cappella. How was it to earn a Gold Medal in such a big international competition?

|

| LY |

I knew then that my sights were set on 1968. I knew right then that I was going to be on the 1968 Olympic team. But let me tell you a little story about that race. Ron Laird won the 20k and Jose Pedraza of Mexico was second in the race. I can’t remember who was favored, but Ron was tough and beat the Mexican. Pedraza was a 20k racer and wasn’t even entered in the 50k. But after he didn’t win the Gold Medal at 20k, he talked to his coach and somehow they got him into the 50k. We started out in the 50k and I moved away from the pack quickly. But Pedraza was literally on my heels. He was right on me. I could move to one side of the street or the other side of the street and he would just follow me, right on my butt. He clipped my shoes and I got the feeling he was trying to take my shoes off. It was frustrating and lasted for a few miles. Finally, he dropped off the pace and ended up dropping out of the race and not finishing. Other than that, there was really no competition there either. The 20k and 50k trials for the 1967 Pan Am Games also gave Ron Laird and me a berth on the European tour right after the Pan Am Games. They were all shorter races which was not my forte. Ron won most of them. We went on a European tour to England, East Germany and Italy. That was my first experience with international race walking against athletes from countries over in Europe.

|

|

| GCR: |

Even though those shorter distances weren’t in your wheel house, did you enjoy soaking in the culture even though you were racing out of your comfort zone?

|

| LY |

There is no doubt about it. A side story is that the last race in which we competed was in Viareggio, Italy. Years later in 1976 when I graduated from college and went to a place in Italy to study, I went to a little town called Pietrasanta, Italy and it was only about 15 miles away from Viareggio. I was still race walking then and didn’t realize where it was until I went out for a fifteen mile walk one day and came upon Viareggio.

|

|

| GCR: |

If we go forward to the next Pan Am Games in 1971 down in Cali, Columbia, you only finished 15 seconds ahead of Mexico’s Gabriel Hernandez. What was the story of that race and how it developed?

|

| LY |

To prepare for the Pan Am Games we trained for two weeks in Florida and it was just hotter than hell down there. I think some of us may have over trained in that heat. So, I wasn’t feeling too great when I got to Columbia. I have vague recollections of how the race started out. It was kind of a long meandering course. It wasn’t a 5k loop. It started on the track and went out on this long winding course into the hinterlands. We were out there in the final stages of the race and I was way out in the lead. There was nobody behind me – believe me – nobody behind me. We were coming down this long straightaway and turned to go up this long hill toward the stadium. I turned and looked and there was nobody there. I was going up this hill knowing I had the Gold Medal in my pocket. I’m not stressing out. I’m not feeling any pressure. Frank Shorter and Kenny Moore were staying in a motel outside the athletes’ village on this hill and stepped out onto the side of the course to see the finish. Shorter steps out and yells, ‘hey Larry – there’s a Mexican right on your ass!’ I turned around and here’s Hernandez on my butt. So, I must kick it into another gear to hold that sonuvagun off. I didn’t remember it was as close as fifteen seconds. Here is my theory: I have no proof, but I think he caught a ride. When I was coming up that hill, you would not believe the jeers and hollering against me. Everyone down there in Cali, Columbia was Hispanic, so there were for the Mexican guy. They were calling, ‘Dirty gringo, the Mexican’s going to get you!’ I wonder if old Hernandez is still alive and if he would ever admit to it. I know something had to happen because he wasn’t within a mile of me. I could see back on the road a mile and there was nobody there. So, I think he caught a ride. That’s just my theory. (note – the next year in the 1972 Olympics 50k race walk, Gabriel Hernandez finished in eighth place over 11 minutes behind Larry Young)

|

|

| GCR: |

In 1976 you aimed to make another Olympic team and you were in third place in the 20k before Larry Walker passed you about 5k from the finish. What kind of shape were you in and how disappointing was it to just miss making your third Olympic team by one place?

|

| LY |

That was very disappointing. I was in great shape until just over a month before the Trials. I was training here in Columbia, Missouri and going up a hill during a training session when I pulled a hamstring muscle in my left leg. It was a bad one. Basically, I had to rehab for four weeks. I think I had one week where I could get back out and felt I was not going to pull the hamstring muscle again by training. I didn’t tell anybody about it except local people who knew I was really in trouble due to my lack of training. That’s why I didn’t have a great race. That Trials was held right next to the track at Hayward Field in Eugene, Oregon. We started on the track and then it was a weird course. They took us out on kind of a loop that went out on some hills and then back down along the side of the track in a back and forth course. I hated that as it’s not a good deal when we have to turn sharp corners. It was also hard on my hamstring muscle. I was struggling from the start of the race, but I’ll never forget that I was in third place and Mr. Blackburn, who oversaw setting up the race, had mis-measured the course and miscounted the laps. Were coming down the straightaway and he said, ‘you have one lap to go.’ I thought that maybe I’d make this team because I was in third place. We went around and came by again and he said, ‘I’m sorry. I misspoke. You still have another lap to go.’ And then he did it another time. He was three laps off and by the third time Larry Walker had already passed me and gone by. If you look at the times from that race, every guy except me set a personal best because it was still a lap short.

|

|

| GCR: |

I did notice when I was researching that the race was only 18,610 meters and was recognized as being 1,390 meters short.

|

| LY |

That is amazing that we were so short. You would hear some different thoughts on that race as I know that Larry Walker has another story. He thinks that I was just using sour grapes and trying to weasel my way onto the Olympic team. I protested the race afterward, though I wasn’t the kind of gu

|

|

| GCR: |

I would agree with you as, if I was in a race and was told I was on the last lap and then multiple times my competitors and I were told there was one more lap it would totally change our strategies and when we made moves and when we kicked. So, obviously the race would have been competed differently if it was officiated properly.

|

| LY |

But, like I said, I wouldn’t have much of a shot at all in Montreal at a medal. But I did manage to get my body back in 50k shape for a National 50k. I would have made the Olympic team if they had a 50k that year.

|

|

| GCR: |

You kept training and then President Carter announced the U.S. would boycott the 1980 Moscow Olympics. How tough was that to swallow?

|

| LY |

I was still training four years later though I wasn’t in the kind of shape I had been in back in 1972. My sculpture career had started to take off and I was putting in a lot of hours and days on the grinder and various other things. I didn’t have the kind of training time I would normally have had, but I still would have made the team in 1980. They pulled the boycott and that was it for me. I decided to retire and to focus on my sculpture career.

|

|

| GCR: |

There was one final international race-walking competition where you competed and that was the 1976 IAAF World 50 km championship at Malmo in Sweden where you finished 21st in 4:16:07. How was that experience, especially with racing in cooler weather?

|

| LY |

I’m surprised I walked that fast because once again I had pulled a hamstring, though it was a slight pull. We had to fly over there, and it was a long flight. I sat in the airplane seat and my muscles tightened up. I made the mistake of getting out on the track soon after we got off the plane and I tried to do a workout. I was doing some wind sprints which I shouldn’t have been doing until I was loosened up good and I tweaked a hamstring. That was one of the reasons why I didn’t have a very good performance. What was unique about that race is that I was grateful to have made the team. As soon as the race was over, I flew into Italy and caught a train down to Pietrasanta, Italy as I had mentioned earlier, where I was going to be studying art. I had received a two-year grant to study sculpture. That trip to Sweden allowed me to make that trip to Italy and to kind of sniff things out a little bit, to figure out where I was going to stay and to look at foundries where I wanted to study. So, that was kind of a combined trip.

|

|

| GCR: |

We’ve been discussing your racing but haven’t touched much on your training except when you mentioned doing 100-mile base weeks. Could you relate how long your long walks were, whether you did tempo walks and intervals and what were your mainstay training sessions so that we can understand the similarities and differences between long distance running and walking?

|

| LY |

I focused on ten- and twelve-mile workouts at below race pace. They were well below race pace. I tried to focus on quality in my workouts. I didn’t just go out and put in miles so that I could say I did 100 miles in a week. No, these were quality miles. In 1972 I was doing ‘two-a-days.’ I’d get out and do my ten to twelve miles in the morning. Then in the evening I’d get out on the track and do some high-speed fartlek-type training. I’d do a quarter mile lap at well below race speed and then 220 yards coasting. That was the kind of meat of my everyday workout. Then on the weekends at least one day on either Saturday or Sunday I would do a twenty to thirty-mile workout depending on what races were coming up.

|

|

| GCR: |

As a race walker you also had to work on technique. What did you do in your early days as a race walker in terms of studying and learning from others and then, as you became more experienced, to develop the balance between strength and flexibility needed to be able to walk fast for such a lengthy period?

|

| LY |

It was a gradual process. A turning point in my technique training was in 1966. We were having a dual meet with Russia in Los Angeles at the Coliseum. Ron Laird and Rudy Haluza made the team and were set to walk against the Russians as only two guys competed in each event. As the meet came closer, the racing gurus got together and decided to put some more guys into the race. I don’t know what they would have done if one of the additional walkers had won the race or broken up the four competitors. But anyway, it gave a few of us a chance to walk. I was out there trying to do my best and I had only been in the sport for less than a year. I got disqualified by a judge by the name of Mike Sekedy. He gave me both cautions which, back in those days, was okay for the same judge to give you two cautions and you were out. So, he gave me the two cautions and threw me out of the race. I’d never been thrown out of a race before though I had received some cautions before. I really couldn’t understand what I was doing wrong. The next week, a guy by the name of Tom Carroll, who was also a judge, but not in that race, told me he had his camera and had been photographing me and taking sequence shots in that race. And he caught me literally off the ground. So, now I had the visuals right there to show me that I was doing it wrong. For almost the next six months I did very little racing, if any at all. It was the off-season and I just focused on training and on long slow distance working on the technique. I was trying to figure out how to keep myself in contact with the ground at all times. It really paid off because, from that point on, I never got another caution in my life. I figured it out and got it down. What also helped was that my dad took video of me in a lot of races. We’d slow it down and look at it in slow motion. We had this little machine where we could load the film and crank it forward one frame at a time to see if there was a loss of contact and to study my technique to figure out what I could do to improve my technique. When I was a kid, I had accidently cut two tendons in my right wrist with a corn knife. I noticed when I walked that each time I went back with my right elbow the right wrist would drop down. I told myself that I had to correct that. If you look at the film of me in 1968 and the film in 1972, you’ll see that I corrected that issue. I changed a few other things to improve my technique between the 1968 and 1972 Olympics. Those extra miles and extra racing added to my strength and endurance.

|

|

| GCR: |

Speaking of strength and endurance, one of your races totally amazed me and that is the 100-mile walk which you did in 18:07:12. What was even more stunning to me is that it was raining outside, and you had to walk in the University of Missouri’s Fieldhouse on an 8-lap-per-mile dirt track. Can you describe the mentally and physically grueling challenge of race walking 800 laps around that dirt track?

|

| LY |

That was a landmark – no doubt about it. When I went into that race, I knew that it was at the end of the season and all that was left was a dual meet with Canada two weeks later. I thought that in two weeks I would recover with no problem. I wasn’t thinking about doing the whole 100 miles. I planned to do fifty miles and see how I felt. After fifty miles I felt okay, so I kept going and I hit 75 miles. I wasn’t feeling so great then, but I was so far into it I thought,’ I’ve got to try to finish this thing.’ If you can find my mile splits for the last two or three miles, I can’t remember if I was under nine-minute miles or under eight-minute miles. I remember that Joe Duncan, who was in charge or the Columbia Track Club and that race, was doing the lap counting. He came up to me after the race and was astonished at my last few miles. My wife, Candy, was there. We were dating at the time and she helped me through with lots of encouragement and food. You’ve got to have food. It’s a 24-hour deal. It took me a little less than that but still you are out there on your feet for a long, long time.

|

|

| GCR: |

Were you able to recover for your season-ending race against the Canadian team?

|

| LY |

When I went into that next race, the dual meet with Canada, we had to travel up there and I was still sore. I wasn’t even sure I should be going to the race, much less how I was going to do. That was a grueling race and was a 50k. I went into it easy and I was back quite a way in the beginning of that race. Finally, about halfway through I was getting warmed up. The muscles started to loosen up and I managed to win the race.

|

|

| GCR: |

That 100-mile race win was one of your 25 American National Titles in distances ranging from two to 100 miles. That’s impressive to win so many championships at various distances. Where do you think this places you in U.S. race walking history with so many championships?

|

| LY |

It is a source of pride without a doubt. I still have all my medals in my trophy case. My National medals are in a half circle with my two Olympic medals hanging up between them. I’m pretty proud.

|

|

| GCR: |

We’ve talked at length about your race-walking competitive career, but it all starts with athletics as a child. So, let’s go back to your childhood – were you playing baseball, basketball and football and other sports?

|

| LY |

Yes, I played all sports – even croquet! I played tennis too. In high school I played football and was a defensive end. That was my position. In grade school I played football in seventh and eighth grade in Richmond. That’s where we lived at the time. Then in 1957 we moved to Buckner, Missouri and that’s where I went to Fort Osage High School. My sophomore, junior and senior years were at Fort Osage. I had already had my taste of football in grade school and wanted to be on the football team at Fort Osage too. I joined the team as a defensive end and wasn’t very fast – I was slow. But I was good at tackling. By the time I was a junior in 1960 was the time I told you that story about seeing the Olympic 50 kilometer walk on television won by Don Thompson of England and that was my first exposure to both the Olympics and race walking. So, the next day I went up to the football field and I was mimicking what I had seen the day before and I started walking around. Coach Marsh, who was the football coach, said, ‘Hey Young, you look pretty good there. Let’s see how fast you can walk the 100-yard dash.’ I did it and he joked, ‘Golly Young, you can walk that almost as fast as you can run!’ We all laughed. My brother and my cousin, Sam Smith, and I would fool around with race walking, but we never got serious about it because there were no race-walking competitions in high school. There was the AAU, but I didn’t know anything about it at the time. So, I kind of forgot about it until five years later until I was discharged from the Navy and moved up to Los Angeles. That’s when I was exposed to those all-comers meets and the rest is history.

|

|

| GCR: |

Let’s chat a bit about your high school running where you ran a school record mile and also were a half-miler. What kind of training and racing were you doing, and did you place at City or County meets and make it to Missouri State competition?

|

| LY |

I did very well in our high school meets. It took me about a year until I knew what I was doing. I ran a 4:48 mile, which was my best, and a 2:10 for the half-mile. I won quite a few races as a high schooler, but they were just local high school races. I was no Jim Ryun, for sure! I was watching Jim Ryun’s times when I was running the mile and knew that I was nowhere in the ballpark. Five years later I was in a meet out in Los Angeles where Jim Ryun was running the mile and I was walking the mile, so that was kind of ironic.

|

|

| GCR: |

When you were in the Navy did you do much running or were you just keeping fit from the normal exercise routine in the military?

|

| LY |

I was a molder in the Navy and I worked in a foundry. So, that’s where I learned how to do Bronze casting and also casting of all kinds of metals. Once I got out of high school and joined the Navy the work was physical, but it didn’t task my lungs. It wasn’t that kind of exercise. I focused on weight work and did a lot of that in the Navy. On board a ship I could do that, stay active and feel like I was keeping my body fit. I was strong. I was a strong kid with a lot of strength and we got the weights out when there wasn’t much work to be done in the foundry. That’s what I did in the Navy. It wasn’t until I got out and moved back up to Los Angeles that I got into the running and walking.

|

|

| GCR: |

After you got that Bronze Medal for the 50k race walk in the 1968 Olympics, how did it come about that Columbia College President Merle Hill called you in and offered you the first full-ride race-walking scholarship in the United States which was unheard of and got you back in the groove for a dual focus on race walking and your art?

|

| LY |

I was already back into the race walk training big time when I went to Columbia College. I took about a year off out in Los Angeles and then some time in 1969 I called my folks up and said, ‘I’m going to try and train for the 1972 Olympics. Can I come home and live with you guys?’ I told them, ‘if you can give me one side of the garage to set up a little foundry, then I’ll do that and train for the 1972 Olympics.’ And so, I moved home and that’s what I did. In 1971 I got a call from Merle Hill. He had heard that I was back in town because I’d been entering races. He heard through the grapevine because he was kind of a race walker himself. He was German and over in Germany they did what they called ‘Volksmarches.’ They would do walks which weren’t really races for most. There was a big 100-mile walk here in Columbia and he would walk a big part of it. Bill Clark, who really started the Columbia Track Club, got this 100-mile walk going in town. Merle Hill got tied in with the race walkers a bit, heard I was in town and called me up to offer me a full scholarship to come race walk for Columbia College. He already had one or two guys and we eventually had three guys so we could enter the NAIA track meets. At that point in time they had added race walking to the NAIA track meets and Columbia College was a member. We went into races and did well because the three of us would wipe everybody out.

|

|

| GCR: |

Didn’t you compete in many, many National Championships while at Columbia College?

|

| LY |

One of the things that Merle Hill offered me was that, in addition to the full-ride scholarship, he would personally send me to all the National Championships where I wanted to compete. There were a bunch of them as race walking has lots of them. That’s why I won so many National titles, because I was able to go to them. If you can’t get to them, you can’t win them. So, Merle sent me in 1971 and 1972 to many races – eight championships in 1972 alone. Merle paid personally out of his own pocket. That’s one of the reasons I did so well – because I had the opportunity to race often.

|

|

| GCR: |

We touched a little on your working as an artist and, as you mentioned, your time in the 1970s to train became somewhat limited because of your art work. Can you discuss some of your large, outdoor sculptures and how the discipline day after day to train as a race walker carried over to the discipline necessary to create these large sculptures?

|

| LY |

I was taking art classes every day. I told Merle when I got the scholarship, ‘I’ll be glad to race walk for Columbia College, but I want to study art too. It worked out great because I was able to study art and race walk at the same time.

|

|

| GCR: |

In the year 2000, other Olympians, such as Al Oerter and Bob Beamon, were members of the ‘Art of the Olympians.’ How neat was it to be a part of that endeavor?

|

| LY |

It’s cool when you get a call from Al Oerter, four-time Olympic Gold Medalist, inviting you to be part of an art team.

|

|

| GCR: |

Now that you’re into your mid-seventies, are you still working strongly on your art projects or have you started slowing down?

|

| LY |

I’m active with my sculpture. I went to our Olympic reunion in Colorado Springs and did a sculpture for that event. Lance Wyman had won the competition to do all the graphics for the 1968 Olympics. He did a different graphic for each of the venues and for every different sport. I got connected with Lance with the idea of taking his graphic images and putting them together in a kind of an Olympic collage for the reunion. I spent quite a bit of time on that. But I’m slowing down, all right. I’ve got a shoulder issue and I’ve got a lower back issue. I still have good functionality but spending eight hours a day on a grinder is not something I’ll be doing much of any more.

|

|

| GCR: |

How about your health and fitness regimen – are you taking spirited walks or working out at the gym?

|

| LY |

Not as much as I should. I get out several days a week to do a little walking and I try to stay fit. Without a goal in front of me it’s a little harder to push myself out that door.

|

|

| GCR: |

Is there anything I missed in your racing or training or art career that I missed which you feel is important to discuss?

|

| LY |

You’ve covered the gamut very well. You asked about the monumental sculptures I have done and those are defined in the sculpture world as anything beyond ten feet. I did my first six-foot sculpture in 1979. That was my first major work of art and was called, ‘The Dance.’ Years earlier when I moved up to Los Angeles, I met a young lady that was involved in modern dance, so I did that for about a year when I was just starting out in race walking. It’s kind of had an indelible effect on me as far as my art work because I do a lot of pieces that incorporate dance and athletic movement. So that influenced my creativity.

|

|

| GCR: |

When you look back at your life from working hard in athletics and academics, military service, dedication to an unlikely athletic pursuit of race-walking and the discipline and creativity needed to succeed in the art of sculpture and the art of your athletic pursuits, what is your philosophy of what helps people to be their best in life with the talents they have been given?

|

| LY |

Perseverance. That’s it. You’ve just got to have perseverance. That’s the one word that comes to me. When I put one of these big monumental sculptures together it’s a lot like that 100-mile walk. It’s perseverance.

|

|

| |

Inside Stuff |

| Hobbies/Interests |

Our family usually gets a regular puzzle out to complete when we have family get-togethers or at the holidays. My wife is a big crossword puzzle fan

|

| Nicknames |

Some people called me ‘Larry Dean’ or ‘L.D.’

|

| Favorite movies |

‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ and ‘Shawshank Redemption’

|

| Favorite TV shows |

‘The Cosbys.’ He had so much talent and why would he throw it all away the way he did?

|

| Favorite music |

I’m a big Bob Dylan fan. If I had to pick one musician out in the world it would be Bob Dylan. As far as my favorite Dylan song, he has so many great songs, but you’ve probably never heard this one. It’s not on one of his albums and you’ve got to go to the underground tapes to find this one. It’s called ‘Foot of Pride.’ The only other person I’ve heard sing this song is Lou Reed and he sings it on Bob Dylan’s 30th Anniversary album. Lou Reed sings this song and just does a remarkable job. That’s one that stands out. Bob Dylan has anthems. He doesn’t just have songs – he has anthems

|

| Favorite literary memory |

I was the lead in my high school senior class play in ‘The Lady is Not for Burning.’ It’s a play that is set in the 15th century. I played the part of the devil. The story is that there was a witch who was in prison and, back in those days, a witch could be put to death. This guy who was in prison with her was the devil and he couldn’t figure out why people were so focused on this girl and weren’t paying attention to him because he was the devil. There was a religious man and the devil was having an argument with him. I still remember one line from it that the devil said to the priest - ‘You bubble-mouthing, fog-blathering, chin-chuntering, chap-flapping, liturgical, turgidical base old man! What about my murders?’ That is the one line I remember from my senior play

|

| First cars |

The first car that I bought and owned was a 1964 MGB. I bought it when I was in the Navy. I got it overseas and I had it shipped to San Francisco. I went up there to pick it up at the shipyard which was quite the occasion. I had it a good while up until 1968 or 1969. I traded it in because I took a job with Pitney-Bowes selling copy machines. After my 1968 Olympic performance I had to go to work and try to make some money. I traded it in on a Volkswagen station wagon so I could haul my copying machines around to show them off

|

| Current cars |

I drive several vehicles. My wife and I have a Toyota Prius. It’s really her car because she puts in a lot of miles in her position as a professor at Truman State University in political science. That’s in Kirksville which is about a hundred miles away from here. I have a full-size Ford van for my sculpture and trailers for hauling it around. Then I have a Honda Civic with 250,000 miles on it that I use to run back and forth to town

|

| First Jobs |

When I was in grade school in Richmond, Missouri I swept floors in a local clothing store. That was probably my first job. In 1965 I got a job with Douglas Aircraft as a template maker. So, I made templates for aircraft parts. I did that for about a year. I quit that job because they wouldn’t allow me to take time off to go to the 1967 Pan Am Games. Now they would jump at the opportunity. Back then they told me they were behind me but couldn’t give me time off. They said they would rehire me, but I would have to come in at the bottom of the rung. That’s the last I saw of template making. I just quit and focused on my training. I lived with a friend of mine and tried to watch my financial situation as I trained for the Pan Am Games

|

| Family |

My wife is Candy and she is a college professor. Elizabeth Butterworth was my mom’s maiden name. My dad’s name was Robert Willis Young. Mom and dad were married around seventy years and died a year apart about eight years ago. I was born in 1943 and my brother was born a couple years before me. My older brother is Craig. He and his wife live in Seattle. Two of his kids live in Seattle and one is in Alaska. I have two kids. My oldest is Zach and he’s 33 years old. My daughter, Sydney, is just behind him at 32 years old. My parents were behind me one hundred percent of the time. My dad took up race walking after I did, and he had an illustrious race-walking career. He was in that Olympic Trials 20k that I told you about in Long Beach and he finished about halfway back in the top twenty in that race. He was in good shape back then. He was my main camera man and my main coach

|

| Pets |

I was born in Independence, Missouri and lived there through grade school up until third grade. Then we moved to the country to a 100-acre farm out between Orrick and Excelsior Springs that was in an area we called a rattlesnake gulch. It was in the woods. My grandad had bought the place and he told my mom and dad that if they wanted to move with the kids down there that they could have the place to live. So, we moved to the country and lived there for five years before we moved to Richmond. All the time we lived there we had all kinds of animals. We had a German Shepherd dog. We had two horses and so my brother and I rode horses all the time. We had goats, sheep, pigs, cows and chickens. We had it all

|

| Favorite breakfast |

Back when I was training oatmeal was my staple before a race. My wife and I have eggs and bacon. And I usually have a couple pieces of raisin bread toast. When we’re on the rode we do something different. We do eat healthy. My wife has some allergies so that keeps me honest

|

| Favorite meal |

I love steak and potatoes. Sweet potatoes are one of my favorites

|

| Favorite beverages |

I like a good glass of wine and, by golly, I like a little scotch occasionally. I like a good scotch. Speyburn is one I like quite a bit

|

| Early race-walking memories |

My first race was in one of those summer all-comers meets. It was a one-mile walk. I had run the mile and half mile and had plenty of time to recover. The walk was at the end of the meet. There were a bunch of walkers there and I thought I’d get in the race because it looked like fun. I finished dead last. There was another mile race walk the next night at another high school and I finished dead last again. It took me a while to get going, but at the end of that first summer of all-comers meets my mile time was down close to eight minutes. I hadn’t done any training since the summer all-comers meets because there weren’t any races. I stopped training and surely didn’t think about the possibility of any Olympic performances. Then there were two indoor meets the following winter – the L.A. Times Invitational and the Times Invitational that were held early in the year. I got an invitation in the mail to the L.A. Times Invitational. Some of the athletes who were going to be at this meet were Jim Ryun and Jim Grelle and Randy Matson. Those were some big names. I was out of shape and had eighteen days to whip myself into some kind of shape. I did but once again I finished dead last in the one-mile walk. It was on the track indoors. Then I did the second meet and came in last again. But some of the walkers started to recognize me as ‘the new guy.’ Ron Laird and Don Denoon were at the top of the sport and both of those guys came up to me and told me there was a ten-mile race walk coming up the next weekend. It was going to be on a course in a park and they told me that I should race. I said, ‘Ten miles! For God’s sake, I’ve never walked over two or three miles in training.’ Anyway, it was a handicap race and since I didn’t have any experience in the sport, they told me I would get a significant handicap and should do well. I went at it and with my handicap I finished in fourth place. This was the first time I realized, ‘Hey, this is a distance sport.’

|

| Race-walking heroes |

I respected anyone who had been in the Olympics and especially who had won a Gold Medal. Now when I look back at films of Don Thompson, his technique was fairly bad, but I must respect him and anyone who puts in the miles and dedicates himself and commits himself. In terms of one particular guy, Ron Laird and I have been good friends for many years but if there was one guy I looked up to it would be him

|

| Greatest race-walking moments |

The two Olympic performances including winning the first Olympic race-walking medal by an American are hard to beat. The 1972 Games 50k was by far my best race. Of course, the 100-miler is indelibly etched in my mind

|

| Worst race-walking moments |

The Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon in 1976 was certainly one. The other was in Badsaroff, East Germany. I had taken time off and we took six walkers over to the World Championships. We weren’t even planning on going until I got phone calls from some of the other walkers who told me we had some money to support the trip and they were trying to put a team together. They needed another 50k guy, but I hadn’t trained much for a couple of months as I had taken some time off. They talked me into it, so I went over and just had a horrible race. I can’t remember what my time was, but I finished it. That was a disappointing race. That was when the Berlin Wall was still up, so I had the experience of going through security and walking a race in East Germany which was rare back in those days. I only didn’t finish one race and that was the 100-miler that I tried again after the 1972 Olympics. I got a muscle pull about 75 miles and ended up dropping out because I didn’t want to injure myself further

|

| Childhood dreams |

I was going to be another Daniel Boone. I had my horse. I had my gun. I had my dog. That’s what I was going to be. I never got the coonskin cap. I tried one on a time or two but never went that far. I was just a kid on a horse with a gun and a dog and I was in seventh heaven

|

| Funny memories |

Right after the 1968 Olympics when I won the Bronze Medal, some of the other walkers were calling it a fluke. I think Tom Dooley was one of them. And they weren’t entirely wrong because I wasn’t even considered a dark horse in that race. They didn’t think I would end up in the top ten, let alone the top three and medal totally, absolutely out of the blue. They saw it as a fluke because of the altitude and because I just got lucky. Fours years later after the 1972 Olympic 50k walk when I got my second Bronze Medal we were all there and had a bottle of champagne. My dad was there too though he didn’t drink any champagne because he was a teetotaler. Everybody had a glass and we raised our glasses. They said, ‘Congratulations, Larry.’ And I said, ‘Just another fluke.’ Dooley was in the room and kind of grinned

|

| Standout memory of a 1968 Olympic teammate |

John Carlos was on the European tour with me in 1967 after the Pan Am Games and that’s where we got to know each other well. He’d get out on the dance floor and you should see that guy dance. If you speak with John and then with Tommie Smith you won’t find two more different guys and different personalities, but they are indelibly linked by that occasion in Mexico City

|

| Favorite places to travel |

Overseas there is no better place than Italy. Here in the U.S. I’ve been all over this country from New York to Los Angeles and done sculptures all over. Los Angeles has a special place in my heart because that’s where I started race walking. I owned a house out there for a while and had a lot of good friends there and love the ocean. I’m where I want to be here in Missouri, so this is my favorite place in the U.S. right at home. We have 35 acres of land in the country. My closest neighbor is about a half mile away from me. I have my six thousand square foot foundry here where I’ve created my sculptures for the last 45 years. I have no real interest in traveling the world any more. I’ve seen it. Been there, done that

|

|

|

|

|

|

|