|

|

|

garycohenrunning.com

garycohenrunning.com

be healthy • get more fit • race faster

| |

|

"All in a Day’s Run" is for competitive runners,

fitness enthusiasts and anyone who needs a "spark" to get healthier by increasing exercise and eating more nutritionally.

Click here for more info or to order

This is what the running elite has to say about "All in a Day's Run":

"Gary's experiences and thoughts are very entertaining, all levels of

runners can relate to them."

Brian Sell — 2008 U.S. Olympic Marathoner

"Each of Gary's essays is a short read with great information on training,

racing and nutrition."

Dave McGillivray — Boston Marathon Race Director

|

|

|

|

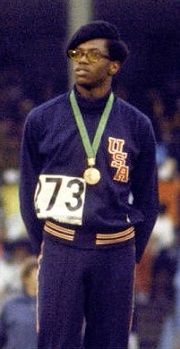

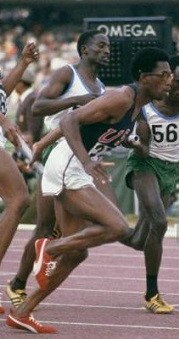

Ron Freeman ran the second leg on the 4 x 400-meter relay at the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games where he and his teammates earned the Gold Medal in a World Record time of 2:56.16. His 43.2 lap on the relay was the fastest 400 meters ever run and transformed the USA’s five-meter deficit into a twenty-meter lead. Ron also competed in the 400 meters at the 1968 Olympics, earning the Bronze Medal in 44.41 seconds. He finished third in the Olympic Trials in 44.62 seconds. He was the only man to beat 1968 Olympic 400-meter Gold Medalist, Lee Evans, in 1968, which he did twice in August at Walnut, California and Eugene, Oregon. At Arizona State, Ron earned the 1968 NCAA Bronze Medal at 400 meters. He won the Western Athletic Conference 440 yards in 1966, 1967 and 1968. Freeman raced as a prep at Thomas Jefferson High School in Elizabeth, New Jersey and won the 1965 New Jersey Group Four State Championship at 440 yards in 46.9 seconds and the 1965 Golden West Championship in 46.8 seconds, both meet records. Ron was named 1965 Track and Field News Top Prep at 440 yards with a best time of 46.6 seconds. His personal best times are: 220 yards – 21.2; 400 meters – 44.41 and 800 meters – 1:50.4. Ron earned a Master of Counseling Psychology at Kean University. He is a founder of the International Medalist Association which makes a positive impact on youth around the world. In conjunction with the U.S. Department of State, Ron worked with youth on military bases in England, Germany, Turkey and Italy. Through his collaboration with UNESCO, the Mali Youth Peace Games were created. Ron subsequently worked for over a dozen years with youth in Guinea and presently champions youth development in Zambia. He was inducted into the Arizona State Hall of Fame in 1985 and received the 2017 ‘Athletes in Excellence Award’ from the Foundation for Global Sports Development. Ron currently resides in Zambia and was extremely generous with his time to spend two-and-a-half hours on the telephone for this interview in May 2023.

|

|

| GCR: |

THE 1968 OLYMPICS – SOCIAL ISSUES AND COMPETITION This year marks the fifty-fifth anniversary of the 1968 Olympics. How important has your performance as a member of the Gold Medal, World Record four by 400-meter relay team and Bronze Medalist in the 400 meters been to give you credibility, open doors and allowed you to mentor and influence others positively since those Olympics?

|

| RF |

Being an Olympian is like being a basketball player or tennis player or football player. Whenever you are successful in a sport or elsewhere, such as an information technology specialist, it does give you more credibility in speaking, working together, reaching out, and getting jobs. To me, being an Olympian gave me some opportunities that I might not have received if I wasn’t an Olympian.

|

|

| GCR: |

Let’s go to the 1968 Olympics for a set of questions that intertwine social issues and competition. First, at the 1968 Olympics, Tommie Smith and John Carlos made that statement for human rights during the medal ceremony for the 200 meters. How did those few minutes and that gesture affect and change you and did you and your teammates consider not competing after they were banned from further Olympic competition?

|

| RF |

We never considered or talked with each other about not competing. What we wanted to do was for all of us to make the Olympic stand so we could make our statement on human rights. After John and Tommy made their statement on the Olympic stand, our goal was to make the stand so we could make our statement. If we didn’t make the stand, it was all for naught. That was our purpose. Certainly, we felt very, very badly about John and Tommy. We didn’t think they did anything that was so bad that they should have been kicked out of the Olympic Games. Yes, they lowered their heads and raised their fists. But they kicked out two of the greatest athletes in the world – why? A Polish athlete did basically the same thing. In the next Olympics, Dave Wottle kept his hat on during the anthem. There were times in the Olympics that athletes were not admonished for not lowering the flag when they passed the President of the host country. That could have been deemed unsportsmanlike. There are many instances in history that could have been classified as bad sportsmanship. It was very heartfelt that John and Tommy had to leave the way they did.

|

|

| GCR: |

I was ten or maybe just eleven years old at the time, but now when I read and watch programs about 1968, just as that moment was a defining line in the lives of many athletes, how parallel is it that the year of 1968 with the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the Vietnam War protests and President Johnson declining to seek re-election, the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, riots in the streets of many cities and at the Democratic National Convention, and more is a defining time in United States history?

|

| RF |

I did realize it during that period and not just because of how athletes of African descent were treated. That is why Harry Edwards started talking about an Olympic boycott. The questions were, ‘Why go to Mexico when we are not treated right at home? Why go to Mexico when the Mexicans were treated just like we were treated at home?’ All that was on our mind. But Kareem Abdul-Jabbar said that he was going to the Olympics. Next, we got past the stage of talking about a boycott. Then our discussion turned to what type of protest we would do in Mexico City. There were problems when we arrived in Mexico City. We saw the folks there demonstrating because of their treatment at home. We all committed to do something and to make our voices heard. Nobody knew what anyone else was going to do. John and Tommy took it to the max. They truly showed what they wanted to show. Some people wore black shorts. Other people wore black socks. Some wore black berets. Many of us showed how we felt about the times, and it was a very powerful statement that we all did as we all did what we wanted to do.

|

|

| GCR: |

It’s interesting too how the realm of sports has put the onus on social issues and helped with forward movement. Along with Jackie Robinson’s stepping forward to desegregate Major League Baseball and Muhammad Ali’s refusing to step forward to serve in the army, the gesture by Tommie Smith and John Carlos, are arguably the three most defining events in the social and political history of sports in the United States. What are your thoughts on how sports figures even to this day are helping to advance social issues in the United States?

|

| RF |

That does still happen. Colin Kaepaernick made his statement a few years ago with the bended knee. A couple basketball players made statements. Some entertainers did so at the Oscars. Many people are using their voices to express their feelings about social injustice and that is a good thing. I feel with Jackie Robinson that was the first big move. But we can even look back at Jesse Owens in the 1936 Olympics. Jesse was highly motivated when he ran because he truly wanted to show Germany that a man of African descent was the best in the world in four events. He made his statement by just winning medals. That was all he had to do. So, there are many ways to show how we feel about social injustice, whether we wear black berets or win in an era when it was so hard to do so. This is happening today. When we watch or go to the Oscars or other events, people use their voices. If a group uses their voice, it is powerful. John and Tommy used their voices, and the world took notice. It is a shame that at the time they were admonished for many years. It hasn’t been until a few years ago that most of the world started saying, ‘They were right.’ People realized that John and Tommy were right. It is great that people can use their voices. I’ve been to countries, and I have recognized this as in many countries people are unable to use their voices in fear of what might happen to them. In America, we have a country where we can use our voice and that is a freedom we should respect and love.

|

|

| GCR: |

You were raised as a child in an impoverished neighborhood and, when people look at poverty and other societal issues, they tend to focus on minority neighborhoods when poverty and social justice doesn’t know color. How much are guns, drugs, disintegrating families, lack of mentors, scarce employment and housing options, and multi-generational dependence on the government affecting not just inner city poor and black citizens, but also rural and white people who are living in poverty in modern days, who are all in this together and who all need our help and how do we turn this around?

|

| RF |

I lived in Guinea, and I live in Zambia, and I don’t see gun problems in either country. There is a small drug problem, but there aren’t people killing people over drugs. People can’t have a gun anywhere in Africa. People are checked and, if you do, you have a problem. The gun issue, looking from the outside in, is a problem that must be solved in the United States, but I don’t know if it can be solved. The criminals have access to guns and that is the problem. Other people that kill folks have access to guns and I don’t know how that can be solved. Opiods are a big issue and that is another problem that I can’t commit to being solved. In Zambia there is a lady who is a Czar of Drugs and Crime, and the government is working heavily in those areas. When I look at the United States, there are so many murders. Every day people are getting killed and it is sad to see. Something must happen, but I can’t see how it will. The automatic weapons, like the AR-15, must stop being sold. But how can they be stopped from being sold unless they are stopped from being sold over the internet? Drugs can be bought on the internet – it’s amazing. There are many things that must be done, but people must get together to try to stop sales of these guns and drugs. After growing up in America and looking at this from here in Zambia, it looks very bad. And young folks are shooting young folks. And young folks are overdosing. And young folks are dying. I pray to God that God will intercede and bring this to a halt. God can stop all of this in a minute and that is where we must go to – to God.

|

|

| GCR: |

Those are some great points and I appreciate you sharing them. Let’s go ahead and switch back to the 1968 Olympics and the competition. After the events surrounding the 200-meter awards ceremony, you raced the 400-meter quarterfinals and semifinals the next day. Were you able to focus emotionally and physically and how did you feel through those two races as you prepared for the final?

|

| RF |

The first fact to mention is that, in the four hundred meters, we ran four races in three days. We had two key races the day before the final. Plus, there was a qualifying heat and final in the relay and we were one team of four runners. There wasn’t an ‘A’ team for the final and a ‘B’ team for qualifying. If you look at what we did with all the qualifying and finals, it was amazing what we were able to do and the times we ran. The altitude didn’t make that much of a difference. We talked about the event from the day before and we felt bad. Lee and I talked about Tommy and John, but we had to move on from that. And Lee knew I was going to kick his butt or try to beat him because I wanted to win it. I wasn’t there to take third place. I was there to win. We were excited with John and Tommy. What was happening though after their stand was that we were getting hate mail. There was a board where we got messages from home and all over the world. Every day we would look at the board to see if we had any messages. We were getting death threats like ‘I’ll kill you, nigger, if you do something on the stand.’ We were getting negative mail and it was bad mail to get. Of course, I was getting great mail from my hometown. They were congratulating me on being there and saying to do it. But we got a lot of hate mail and all that was also on our minds. Other than that, it all worked out. I had to put thoughts of Tommy and John aside and focus on me because the main objective was to make it to the Olympic stand. I knew if my focus was broken, there were a lot of good athletes there and, with those many rounds, anything could happen. We had to run forty-four high or forty-five low to make it to the next round. So, we had to put those two guys out of our mind though we were saddened by their departure.

|

|

| GCR: |

After making it through those two rounds, the final was the next day. Can you take us through the Olympic 400-meter final as you were in lane one, with Larry James right next to you in lane two and Lee Evans out in lane six as the three of you raced for Gold with Evans and James finishing in front of you as they both went sub-44 seconds?

|

| RF |

When I found out I was in lane one, that broke my focus. That is all turns in lane one for the four hundred meters. I knew it was going to be a miracle for me to win with Lee all the way out in lane six. So, I had to make a choice because I was not truly a sprinter-quarter miler. My best event would have been the eight hundred meters. I was an eight hundred meter – quarter miler in high school. I could have gone right out with Larry James in lane two. But I made a decision that I shouldn’t go out with Larry because, if I did, there was a possibility that I wouldn’t have anything left coming home in the last one hundred meters. I didn’t know, but I had to make that choice because if I didn’t go out with Larry, I might have been too far behind to even take third place. But I made the decision not to go out with him. If you look at the video, I was last at two hundred meters. Again, I was an eight hundred meter – quarter miler and I decided to wait. From the 200-meter point on I let it all hang out and I started kicking. I used up everything on the track and came in third. I wanted to run for the Gold Medal but had to be careful in lane one after running those two hard races the day before.

|

|

| GCR: |

How exciting was it for you three to be on the medal stand together and were there mixed emotions in your head when Lee, Larry and you received your medals and while the anthem was playing?

|

| RF |

If I see an athlete today do something that they were trying to do in person or on Facebook, I say or type three words, ‘You did it!’ Because I know how hard it is to have a goal in your mind – and goals are dreams in your mind – and then to do it. That’s the way I felt on the Olympic stand. I did it. We did it. We got there. I didn’t take first place. I didn’t take second. But we all made it onto the victory stand together because we knew we wanted to share our voices, the three of us together. We didn’t want one of us or two of us to make it. We wanted three on the victory stand so we could give our voice and attitude toward how we felt in the world.

|

|

| GCR: |

What was the spirit and confidence level of the relay team before the race?

|

| RF |

Larry, Lee, Vince and I had a song going into the relay. That song was, ‘Two-fifty-five and that ain’t no jive.’ When we were warming up around other teams, if you can imagine, we were singing, ‘Two-fifty-five and that ain’t no jive.’ We were singing and bouncing and smiling to that song. We had worked out how we could definitely run a 2:55. There was no doubt in our minds. The athletes today don’t look at their races and figure out what they can run, and they don’t have it worked out. We knew that, if Vince dropped a forty-four point that we could run 2:55. And, if all of us in procession dropped forty-four point, that 2:55 or lower was a done deal. Since we had that song, ‘Two-fifty-five and that ain’t no jive,’ we knew what we had to do. I knew I had to run forty-four point. We didn’t have an ‘A’ team and a ‘B’ team, we had all run a lot of races and that was on my mind. We had broken the World Record at the Olympic Trials with a 2:58 and we wanted to take that down and put a time out there that would last for the next thirty years.

|

|

| GCR: |

In the four by 400-meter final the predictions were that Lee Evans and Larry James would run the fastest legs. You took the baton from Vince Matthews, who led off, a few meters down, caught Munyoro Nyamau of Kenya, and led by five meters after 200 meters of your leg. Can you describe how you felt during the last half of your leg as you ran the fastest ever split of 43.2 seconds and stretched the lead to twenty meters when you handed off to Larry James?

|

| RF |

Usually, the second man is the weakest leg on a four by 400-meter relay team. Coach Stan Wright said, ‘Okay, Freemen, you’ve got to run.’ There was a lot of concern because of how the Kenyans and other teams were running. I didn’t have any unease about me. A facet of our U.S. relay team is that we used something that was never used before in the four by 400-meter relay and hasn’t been used since. We were a four by 400-meter relay team using four by 100-meter relay blind passes. We looked back and when the approaching runner hit his mark, we went. We didn’t stand sideways and take three steps and then go. We did the four by 100-meter relay underhand passes which has never been talked about. Look at that video and it is amazing. Coach Wright gave that plan to us and we trained with that. Again, I’m an 800-meter / quarter miler and I don’t want anyone to catch me. Vince had several days where he lay off because he wasn’t in the open four hundred meters. Then he couldn’t see anyone because he was in lane one. He was holding back a bit, but he had to get it to me with that four by 100-meter pass and that is what Vince did. When I got the stick, the first Kenyan had run forty-four point something and had run his tail off. I knew the Kenyans were sharp. The Kenyan guy on my leg was sharp and I didn’t want to jump on him right away. I had in my mind to keep close and to start racing from three hundred meters out. I started kicking from three hundred meters. Usually, a runner will cut right in, and I slanted right in so I was in front going into the two-hundred-meter mark and I wouldn’t waste any time. I had that figured in my head. I had never slanted in like that before, but the workouts Lee and I were doing were some heavy workouts. We were training partners. Lee played a significant role in me making the Olympic team. I had never worked out with anybody, period, in my life. No one. The first time I worked out with anybody was with Lee. We challenged each other during the workouts and that was a fun time. I felt good and thought that the worst thing that could happen was that I could die very badly on the homestretch. But who did I have ahead? I had the mighty burner, Larry James, coming up and I kept going. The bear didn’t jump on me. I had no idea what I was running but I was ahead. I knew that the worst thing that would happen if I died was that Larry had it and Lee was going to bring it home. So, it didn’t bother me that I started racing from the three hundred. And that is what I did. I raced for three hundred meters.

|

|

| GCR: |

How satisfying was it to watch as both Larry James and Lee Evans extended the lead over the next minute-and-a-half, and your foursome obliterated the World Record?

|

| RF |

What amazed me was that, as I was racing, with that four-by 100-meter blind pass, I couldn’t slow down. I had to speed up. I couldn’t slow down and have Larry wait. Larry took off but I was right on his tail and gave him the baton in stride. I was happy about that, and it was the most exciting part of my race. I didn’t see much of Larry’s run because I was tired. But everyone knew what they had to do. Vince did what he had to do. I did what I had to do. We all had roles to play, and it all worked out right. I think that, if anyone else on the team was in my second spot, they would have run as fast or faster. It felt good to see Lee run what he did and to come to the line with no infractions. That felt good. We were a team. Everybody played their role, and we were happy.

|

|

| GCR: |

When an athlete wins an individual medal, they are on the top step of the podium by themselves. How joyful was it to share the Gold Medal with your three teammates and what are your thoughts about how the four of you made a statement as you wore black socks and black berets during the award ceremony?

|

| RF |

It was quite rewarding. We made it to the stand to do what we wanted to do, and we did what we wanted to do. What people have not heard about is what Avery Brundage said to us after we received our medals in the four hundred meters and before we ran the relay. He said some things that were not good for young athletes to hear before their final race. He said that if we did anything like John and Tommy did, we were going to lose our scholarships, we wouldn’t be able to race again, and he made a couple other choice statements. He told us that before our final race. This shows you how strong we were psychologically because that could have put doubt in our minds and how we ran. The way he said it was bad. The four of us talked about that statement. He was a racist and tried to use his voice to bring us down and lose our focus. We talked about that and knew we had to let that go and we did our thing.

|

|

| GCR: |

Before competing in the Olympics, an athlete must make the team and, as you mentioned, Lee Evans was instrumental in helping you to do that. How tough was that Olympic Trials race as you came off the final turn in sixth place and had some work to do before you passed Jim Kemp and Hal Francis with seventy-five meters to go and caught Vince Matthews with twenty meters to go to secure your spot in the top three? And how was that initial realization and feeling that you were an Olympian in an individual event?

|

| RF |

I heard a little birdie in my ear coming off that last turn. That birdie was John Carlos (laughing). Before the race John Carlos said to me, ‘When you come off that turn, you’ve got to lift. Lift, lift, lift.’ When I came off that turn and saw where I was, the only thing I could do was lift my legs. It wasn’t even about speed. That was the only thing I could do. I knew that, if I lifted my legs, I would get speed. There is a different action when you lift. I heard John in my ear, ‘Lift, lift, lift.’ I started lifting my legs and that saved me. I have to give John his dues on that.

|

|

| GCR: |

WORKING WITH YOUTH IN THE UNITED STATES AND INTERNATIONALLY Before we discuss details about your youth and competitions in high school and college, let’s go through what you have done working with youngsters throughout your lifetime. After you received your master’s degree in counseling psychology and became involved in your community, what did you do to work with youth in your community and how did you and others found the International Medalist Association to expand and grow your work?

|

| RF |

In developing the International Medalist Association, the idea came after working with several other organizations. What I decided to do was to use my Olympic experience and my Olympic contacts to do more specifically for youth and young folks. I worked as a fund raiser for a couple of organizations, and I received a lot of support from my Olympic family. If I wanted to raise money for a university, I would contact Florence Griffith-Joyner. Flojo and her husband, Al Joyner, were very supportive of me when I put on fund raisers that honored her and other Olympians. We would bring ten or fifteen Olympians together to raise money. There was another situation near Washington, D.C. and I called on Carl Lewis. He helped me do a fundraising video. We honored Carl and he gave the attendees an autographed book. He was part of my Olympic family. With IMA I called on my Olympic family to help me put on camps. So, my Olympic family has always been with me including, particularly, the United States Olympians Association. If I was holding an event in the United States or outside of the country, they would send me t-shirts or caps to hand out to the youth. We are a family that sticks together and grows together.

|

|

| GCR: |

What did you do and how important was it to have a strong team working with you when you set up youth programs in Baltimore, Maryland?

|

| RF |

I have a team with me, and I don’t do as much as my team does it all. I think up the programs and design them. When I was working with youth in Baltimore, Maryland, we designed a program to help elementary school youngsters. Our first program was funded by the U.S. Department of Education for many years. We went into the inner city of Baltimore and selected a school that had an outstanding principal. The school was in a very poor neighborhood and was across the street from boarded up buildings. There were crack vials on the street. This was the type of area. One thing I noticed when I initially went to interview the principal was that the school had no graffiti and the students in the school were organized. The principal was a male. We asked him if we could write and submit a million-dollar proposal for him that would add programs to his school curriculum. We would include an after-school program, request air conditioners on the first floor, and propose to turn the library into a computer center. We did this and had ten or fifteen computers that were networked together. It was amazing how students went to use the computer center under supervision. We added recreational, social and cultural programs. It was a three- or four-hour program and, within that program, the students ate a great dinner because they were eligible for one hundred percent free meals. They received their breakfast from a government program, and we provided dinner. We also transported the student home. I have learned throughout the years in many settings, including this one, when we give youngsters information that can help them grow, they might hear, but they don’t listen. If we play a certain type of music, a youngster will listen. What we wanted to do was to get the youngsters to listen, so we had them hear messages from Olympians. It was amazing how the Olympians came to my program to help us out.

|

|

| GCR: |

Who were some of the Olympians you brought in to speak to the children that caught their attention?

|

| RF |

We brought in Mal Whitfield and he talked about things from his childhood. Who would think that a child in elementary school would listen to a person Mal’s age, understand and listen with joy? But our youngsters listened to Mal and, when he finished, they stood up and they clapped because he was an Olympian and due to the way he put his story together. We had others come in to speak, such as John Carlos, Jair Lynch, Lynnette Love, and so many other Olympians that the kids listened to. After about ten or twelve Olympians came in to speak, we brought in Michael Phelps. He came to a school that was ninety-nine percent Americans of African descent who were poor. It was at night in an area where we provided a police escort for him, his mother and his coach. When he started speaking, immediately the kids’ eyes opened, and they got brighter. By the time he finished, the kids rushed to the stage. Children were grabbing onto his legs and his chest, and they were so happy. They did understand what he was saying. This is one of the joys we have at IMA that I truly appreciated.

|

|

| GCR: |

Can you describe how other initiatives, such as youth camps, opened the children’s eyes to a new world?

|

| RF |

There was an instance where there were two gangs in Baltimore, the east side gang and the west side gang. Can you imagine us taking fifty youngsters, both male and female, to the University of Maryland – Eastern Shore, for a camp for a week? These youngsters, I am sure, had not gone further than a five-mile radius of their homes. When we arrived, there were some problems. I didn’t see anyone selling drugs, but beepers were going off. I told them to turn their beepers off and there was a bit of a hassle when we got on the bus. To tell you the truth, I had to threaten the youngsters. After that threat, they behaved for a week. They stayed in college dormitory rooms and ate in the college dining rooms. They saw green grass. It was lovely for the boys and girls. We had a couple former pro baseball players come in to talk about life, drugs and growing. We had women talk to the girls about becoming a woman and how to live and how to grow. We had three-on-three basketball games. With these so called ‘bad guys’ I didn’t see anything bad happen at the camp. My ten-year-old son, Malcolm, was with them. As it turned out, we had tournaments and the last one we had was a three-on-three tournament and my son, Malcolm, was selected by two guys to play on their team. They won and it was a miracle. Malcolm did break his collarbone and had to go to the hospital. All the guys and girls went to the hospital to see him, and they pulled together. This program lasted for about twenty years. We took three kids to the winter Olympic Games. We took the youth on a five-day retreat. There was a black girls’ retreat and black boys’ retreat. It was at a beautiful facility in Elkton, West Virginia where we had men of African descent and women of African descent come and talk to the youth. These programs hadn’t been done before. It gave me the latitude to dream. What I did then and what I do now is I dream. I dreamed of being an Olympic athlete and I dream of how I can support youth. There was one more important aspect of what we did in Baltimore. We sat the gangs down and the other part of that program was to get the gang members ready for the world of work. We reached out to an employment agency in Baltimore, and they said they would hire those folks we submitted if they had good character.

|

|

| GCR: |

Can you describe the IMA’s first overseas outreach on military bases in Europe?

|

| RF |

The next area with IMA is that we took our program to Europe. We took it to England, Italy, Germany and Turkey. Can you imagine that? We knew there were American youth on the military bases, specifically Air Force, in these foreign countries. What we wanted to do was to put a smile on their faces by having them see American Olympians and coaches at their facilities. We provided fitness activities and games and played with them. It was a great program, and the kids were happy. I remember this one instance where a parent had two sons. The mother said, ‘Coach Freeman, these guys act up. If they act up and start wilding out, you call me, I’ll come right away, and give them discipline.’ I told her I was sure that wouldn’t happen. As it turned out, these two boys won the outstanding athletes awards for these programs because it gave them a chance to run and have fun and to communicate with others.

|

|

| GCR: |

With the success in the U.S. and in Europe, what prompted you to expand to work with Africa youth?

|

| RF |

After that, I said, ‘It’s time for me to go home.’ I truly wanted to start working with youth in Africa. We started getting grants from the U.S. Department of State. The first grant we received was from the International Olympic Committee and Juan Samaranch. How that came about was because I had been introduced by Willie Banks to a person in UNESCO and I became very active. That person was very impressed with what I wanted to do, and he introduced me to the Director of UNESCO. Juan Samaranch, President of the International Olympic Committee, was also at that meeting where a Memo of Understanding was signed between IMA and UNESCO to do what were called sabbatical support programs in Africa. That got us started in Africa. When I was at that final meeting with UNESCO, I was given the opportunity to organize and start a major five-mile race that started with their half marathon race. So, it was very rewarding for me to be there at that time. That opened the doors to me in Africa. From the UNESCO program, we received U.S. Department of State grants for programs in several African countries. Some of the outstanding things we did were that Lee Evans, and I went to Madagascar. There we had a team led by Bill Hurd who, at that time, was an outstanding eye surgeon. Bill put together a group that coordinated with the Veterans Administration and procured laser operating equipment. Ambassador Barnes contacted the Clinton Foundation to get funding for the equipment to be sent overseas. After about a year, we were able to go to Madagascar with the equipment. The team of doctors performed eye examinations and amazing eye surgeries throughout the country. One of the doctors had collected thousands of eyeglasses. We gave them to the eyeglass stores, and they sold them to the people for a dollar apiece because we didn’t want to go there and take business away from the stores and the local economy. People walked for miles when they heard about the program. I loved that program and Bill Hurd is authoring a book on his experience in Madagascar and other African countries.

|

|

| GCR: |

After that great start in Africa, what was the next program that you and your team implemented?

|

| RF |

Another program that was impactful for thousands of youths was when the State Department provided funds for us to take coaches to Mali and to train coaches there in athletics and basketball. We went a day beforehand to Timbuktu… During those trips I saw some amazing things on the bus rides. There was such joy from the Imams. On our last trip, we had about ten Imams around the table. Elnora Webster and Larry Adhill were there with us. Elnora asked to say a prayer and I looked at an Imam. He nodded his head and Elnora said a prayer. Everybody hugged each other and we were joyful. I wondered what else we could do instead of ending the program. So, I reached out to the State Department and told them a vision I had to bring youth together and the different factions of adults in that country. They asked me what I wanted to do, and I said, after some thought, ‘I would like to call this event the Mali Youth Peace Games.’ We laid out some information for them to look at and they bought it. So, the Mali Youth Peace Games were designed and then were ready to go. I selected an NGO that I thought could pull off the Games and add to it. They did it and included wheelchair athletes and senior athletes. When I came back to see it, I was so happy that we thought of that program, the United Nations of Guinea contacted me.

|

|

| GCR: |

What led you to go to Guinea, on the west-central coast of Africa, to further develop your team’s reach to youth in Africa and what was your initial plan for outreach in Guinea?

|

| RF |

They said, ‘Mr. Freeman, we heard about the Peace Games in Mali, and we would like to do something bigger and better.’ I left Mali and went to Guinea and asked them what they had in mind. They said, ‘We don’t have anything in mind. We brought you over here to design it.’ I said, ‘Bigger and Better.’ Then I put my thinking cap on, and I started dreaming again about what would be bigger and better. A lot of the time I think of things that have never been done and I have a talented team that is helping me do this. I discussed the thoughts with my team and what we came up with was the Mano River Union Peace Games. The Mano River Union has Guinea, Celyon, Liberia and Ivory Coast. We thought it would be great to bring youth together in an Olympic type setting not only to compete, but to have workshops and seminars. Unfortunately, there were two conflicts going on at that time. One conflict was between youth from Ivory Coast and Guinea. The other was between youth from Liberia and Celyon. We selected hotels and planned to put the French-speaking youth in one hotel and the English-speaking youth in the other hotel. We had programs designed for leadership development in each hotel. But, about seven weeks before the program was supposed to be held, there was a coupe in Guinea, and we never had a chance to pull off the Mano River Union Peace Games.

|

|

| GCR: |

Since you were at a critical juncture, what was your though process behind staying in Guinea and changing focus?

|

| RF |

At that time, I decided to stay. I called my family and told them that I was going to stay because I wanted to finish what I started. The rest is history. I stayed in Guinea for fourteen or fifteen years. In Guinea and many African countries, there are no recreation programs. When I look back on my life, I was designed to be doing humanitarian work. When I came to Africa, the word ‘recreation’ wasn’t mentioned. Kids either kicked a can around if they were small boys or played kick the can soccer. If they were lucky enough to get a real ball, they would play real soccer or, as it is called in Africa, football. The girls would stretch a line across and straddle a rope which supposedly was a form of jump rope. But girls had no recreation activities. I was thinking about the Mano River Union Peace Games where we were going to have athletics, but that wasn’t going to happen. So, I decided that we should bring recreation to Guinea. I wondered how to get the International Medalist Association recognized. At that time, Edwin Moses was available, and I asked him to come and work with me and another Olympian from Kenya to talk about developing sports in Guinea. Edwin Moses came and so did a French-speaking friend of mine who had gone to UCLA. He was a white guy. We put on an amazing program that included school youth, ministers and sports officials in Calekry. That is what kicked off IMA in Guinea. We got a small grant from the embassy and the program was designed to promote recreational activities which had never been done there. We got going and had a hundred football (soccer) games a week in our five areas. We had similar numbers for three-on-three basketball. The football games were five against five with three girls and two boys on a team. That was a new type of game in 2006. The programs in Calekry grew from that point on.

|

|

| GCR: |

What was the impetus for what seems to be an unlikely turn, the Double Dutch jump rope program?

|

| RF |

I contacted an associate of mine in America and said, ‘Beatrice, can you still jump rope?’ She said she could, so we brought her over and started the Double Dutch jump rope program which was an amazing program. We went from no recreation for girls to a new program where girls could learn to jump single rope and double rope and they loved it. We grew the program to thirty or forty thousand girls in the country who were jumping rope. We organized Double Dutch Championships and had over a thousand girls walking into a stadium before jumping rope. And this is in a country that knew nothing about this and never had the activity. For these programs, we had to train coaches. In any country that I go to, I always have a coaches training program. The coaches in the U.S. are concerned about how youth are doing in their sport and in the classroom. In Africa, the concern is how the youth runs, jumps or throws. There isn’t the personal involvement of the coach in academics or nutrition. In all my coaches training programs, we would focus on how to communicate with an athlete and why. That has helped many athletes in countries where we work through IMA. In Guinea, we wanted the coaches to get ready to train the kids to go to school and to understand the importance of going to school. We focused on the girls because, in many African countries, girls are the last to go to school and the last to go to college. They are trained as young girls to do housework for a husband. We wanted to build their self-esteem which is what the program in Guinea has done. We have had girls go to universities in America and do well. I’m in contact with some girls and boys who are now young women and men in their mid-twenties. The Double Dutch program has a mission toward becoming an Olympic sport and I helped them set up a fund raiser in that area. Basically, we build self-esteem, grow leadership skills, and give hope to youngsters.

|

|

| GCR: |

Health care isn’t as strong in Guinea as we might hope. Can you give any examples of this?

|

| RF |

Here is an example of how things can happen in Guinea. There was a young girl about ten years old years ago who was very small. She could take a single jump rope and go inside a Double Dutch rope swinging the single rope. She was amazing! Then she started missing from our competitions and I asked the coach where she was. He told me, ‘She doesn’t jump anymore.’ When I asked why, she said, ‘The girl broke her arm and they cut it off because she didn’t have the money for a cast.’ And the coach hadn’t reached out to my staff or me. It was a minimal amount of money, and we would have paid to put a cast on her arm. But they decided to cut her arm off. I still cry over that.

|

|

| GCR: |

Another area that we take for granted in the United States is having proper clothing and shoes. What can you tell us about partnering with Toms Shoes?

|

| RF |

Several years ago, around 2016, I connected with Toms Shoes and that program was amazing. They provided seventy-five to eighty thousand pairs of shoes each year to girls and boys. Each child had to commit to going to school. When Ebola and Covid spread, it knocked the programs back though I still got support from the Olympians. I didn’t attend the programs during Covid because, even though we gave the kids masks, they didn’t wear them. My staff handled the programs, and they still went well. This was the first shoe program ever in West Africa and it went well. What did the shoes mean? These were fifty-dollar shoes and meant that kids had something on their feet when they played soccer. More importantly, many youngsters couldn’t attend school because their shoes were flip-flops, and it increased the number of youngsters who could go to school. And these Toms Shoes were very good quality shoes.

|

|

| GCR: |

After over a decade of focus primarily on Guinea, now you are working with youth in Zambia. What were the reasons behind leaving Guinea and how did you decide to settle in Zambia?

|

| RF |

One of the reasons I selected to work in Guinea is that it is a very poor country. It is one of the poorest countries in west Africa. I could have gone to Ghana, but a lot of progress was happening there, and it was a great country. There was very little happening in Guinea and many areas I could start up and make an impact. As I got older, I knew that Guinea would not be the country in which I would retire. Even though the country is better now, there is still much lacking in infrastructure. There aren’t hospitals that offer a reasonable level of heath care at my age and that was a consideration. I was going to stay there if not for the medical aspects. I did leave behind a good team in Guinea to continue with the projects they were taught to conduct. They love me in Guinea and want me to come back. Guinea is a lovely country. It’s one of the most beautiful countries I have been to. When travelling through Guinea, there are the waterfalls, and it is beautiful. But at my age I didn’t feel I would be comfortable. When I was getting ready to leave, I started looking at where I wanted to go. I looked at Botswana, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia and South Africa. All those countries had good medical services and were attractive for other reasons as they had features I liked. Zambia is a sleeping giant. Botswana has good four-hundred-meter runners. Kenya – we can’t say anything with all those great distance runners. Tanzania and South Africa are also very good countries. I looked at Zambia, and its beauty, and followed their Olympic Committee online. I have a friend from outside Zambia that is being recruited to come here to help work with youth and the sport of break dancing for the Olympic Games. Then I was talking to Edwin Moses and mentioned I was thinking about going to Zambia. He said, ‘You know who is in Zambia? Samuel Matete. He is the man and the goat there. He is the G-O-A-T.’ If you ask any Olympian around the world about Zambia, they know and respect Samuel Matete.

|

|

| GCR: |

My most recent interview was with Derrick Adkins, and we talked a lot about Samuel Matete because the two of them were intertwined throughout their collegiate and professional careers. Derrick and I had a lot of conversations about Samuel because they were fierce competitors and great friends.

|

| RF |

Derrick Adkins was a great competitor with Samuel. So then, what I did was to decide that it was a done deal to go to Zambia since Samuel was such a nice guy. In Zambia, they are making some wonderful progress in sports. I think that by the Los Angeles Olympics there are going to be multiple sports teams coming from Zambia that are going to have a chance to get on the medal stand. There is focus on judo, athletics, football and women’s football. These teams will challenge for medals. I see the way they are being trained and their meetings are held. The sports federations are working hard, and the Olympic Committee is outstanding. What I hope to do is to get more U.S. Olympians and outstanding sports coaches involved in this country to support the various federations. I hope to do this for as long as I’m here. I could be here for a while, though Nigeria is recruiting me to go there. Right now, I’m very excited about Zambia and working with the Samuel Matete Athletic Foundation, which is a growing foundation.

|

|

| GCR: |

What programs have you and your team started implementing in Zambia as you work with their youth and how excited are you to be there?

|

| RF |

We are providing some help to the tennis association to get them free tennis balls. I’m working with a young lady here in Zambia who is very interested in heading up my Double Dutch program. She is in the process of starting it up and has a list of schools that want the program. These schools aren’t in Lusaka but are in the copper belt. I have given her all my information; we talk frequently, and I would be very happy if she makes progress. She is excited about Double Dutch and possibly the five-on-five mixed football. I’m retired and this is what I’m doing in Zambia. It’s a very lovely country. There are so many places that are great to see. There are ten or fifteen animal preserves that are outstanding. There are lions, tigers, and giraffes. There are the best waterfalls in the world and several other waterfalls. So, it is a wonderful country, a country with history, a country with museums and a country that has the number one four-hundred-meter runner in the world, Muzala Samukonga. Zambia hardly runs in any major competitions, so this guy has a chance to break the World Record. This is a beautiful country; the Zambians are great people, and this is going to be an exciting country. It’s like being at home.

|

|

| GCR: |

FORMATIVE YEARS AND HIGH SCHOOL RUNNING It has been exciting hearing you speak about how you have helped youth in the U.S. and Africa. Let’s go way back to your childhood. Didn’t you have some health issues to overcome as a child before you were able to compete in strenuous sporting activities?

|

| RF |

I was born a couple of months prematurely and weighed less than four pounds. In fact, at birth I had to have a hernia operation. I was so small that my mother carried me around on a pillow. That’s how small I was. I started wearing glasses when I was five or six years old because, when I was in the incubator, some air got in and gave me astigmatism in my eyes.

|

|

| GCR: |

Can you describe your family, your upbringing and your mentors as a youth?

|

| RF |

I come from a poor family. My father worked for a mining company. My mother cleaned houses. I was very proud of my mom for cleaning houses but, in my senior year of high school, she got a nursing degree. My father worked for thirty years for a company called Alcan that is now called Rio Tinto. It is one of the largest mining companies in the world and my father moved up to hire people and work in management. I tell kids in Africa that, if they are cleaning houses, that is good as they are making some money. But they can also grow because that is what my mother did, and she became a nurse at the hospital where I was born. I share that story but the big story I tell them is that I didn’t come up with a silver spoon in my mouth. I had much support. One guy was Doctor Handling, who was a surgeon. I lived in the hood but, around the corner, where I used to go and play with my friends, there was a vacant piece of property. At some point, a group of very rich people – doctors, school principals, dentists, undertakers and lawyers – rich, black people – bought that property. On that property they built two clay tennis courts. If you can imagine, a few weeks later that property had turned into a tennis club. We saw black people all dressed in white. The girls were beautiful. I had five friends and we used to go to a stoop right across from the tennis court and sit and watch. The adults were playing and cooking hot dogs and hamburgers a couple times a month. We were very excited. After a few weeks, this doctor named Doctor handling reached out and asked us,’ Would you boys like to learn to play tennis?’ I don’t know if middle class folks or upper middle-class folks do that today – to reach down to poor kids to ask them if they would like to join in. But that’s what they did for us. Out of the five of us, three went to college. None of us were thinking about college because, even if we did, our parents didn’t have the money. Two became CIAA champions and one became the best in America along with Arthur Ashe. That is Art Carrington. He went to the U.S. Open and is today the primary source of African American tennis history. These are friends I still communicate with today. We were junior high school classmates and are in touch today.

|

|

| GCR: |

You spoke a bit about the tennis club and recreational club. In what sports did you take part as a youth?

|

| RF |

When I was growing up, I played baseball, basketball and tennis. The City of Elizabeth Recreation Department was active and so was the Union County Recreation Department. I was a poor child, but I used to walk twenty or thirty minutes from my house to downtown and go to a recreational center and play. I would also go in the wading pool. I would walk around the corner from my house to the city recreation center. There was also a field where we played baseball games at night. I played all kinds of games – tether ball, dodge ball, jacks and table tennis. But every sport had to do with me seeing a ball. So, I wasn’t the best I could be. I knew that my parents weren’t going to be able to pay for me to go to college. I knew I was being geared up to work in a mining company. It was Metals Disintegrating, but now is called Rio Tinto. That is where my father worked for many years. He would take me to visit, and I would wear a mask when we went into the smelting department. But I did have going to college in my mind. I took college prep courses. I was hopeful of getting an academic scholarship. That may have been possible at a black university, but at a white university it was shaky. I knew I wasn’t good at any type of team sport. The coaches would have to decide whether to even put me in. When I played with my guys and we got together to play sandlot football or sandlot baseball, I was usually the last to be picked.

|

|

| GCR: |

How did you decide to start organized running and were you successful right away?

|

| RF |

I decided my junior year and senior year to start running track. On the same stoop one day across from the tennis court, I was there with five or so of my neighborhood brothers. We were talking and everyone knew that I liked Coca-Cola. I said, ‘Guys, I bet you that I can run around this block.’ They all said that I couldn’t because it was a very, very long block. They challenged me and said everybody would buy me a Coke, if I could, from the Coke machine around the corner. I did it. We didn’t have watches to time me, but I did it in a reasonable amount of time. Everybody was just as surprised as me because I wasn’t tired. That was one of the reasons that caused me to start running and get on to cross country. Some of my friends that are still friends to this day always mention when I ran around that block. I did so-so in cross country my junior year but, my senior year, I started running well. I won a couple meets. In those days, we started cross country in October. We went to the doctor for a medical exam in November. When I got my exam, the doctor told me that I could not run cross country and could not run at all anymore. I couldn’t even go to gym class because I had a heart murmur. The only way I could be allowed to participate was if I had a cauterization. I asked when he could do the procedure. He said he couldn’t, but he could send me to a doctor who could, and it would cost three hundred dollars. Back in that time, three hundred dollars could have been a million dollars to my parents. My father said I shouldn’t worry because he had me set up to have an excellent job. Psychologically it hurt, but I dealt with it. I didn’t do any training. October was the last time I trained. In December I received a phone call, and somebody had paid the three hundred dollars for me. I never found out who paid for me to have the cauterization. I had it and was told I could run.

|

|

| GCR: |

Now that you were able to run again, how motivated were you to do very well?

|

| RF |

I started training again. I got up in the morning to run. I began doing speed workouts. Nobody told me what to do, but I started doing my thing. Some of my friends came back from a black college tour and told me they heard that somebody had run a 46.6. I didn’t know what a 400-meter time was. I didn’t know what a 200-meter time was. We didn’t know times. Track and field wasn’t on television much. They told me they saw that this college guy had run a 46.6 and his name was Nick Lee. One of the colleges they went to was Morgan State and that is where they met Nick Lee. When they told him they had a friend who was running four hundred meters, Nick Lee told them he had run 46.6. When they told me, I didn’t know Nick Lee, but I put ’46.6’ on my sweatshirt, the back of the door in my room, the back of the bathroom door and on the kitchen cabinets. Everywhere I looked, I saw ’46.6.’ I had no idea how much it would take to run that fast. As it turns out, when I started training three hours a day and when I went into indoor season, I was very aggressive in my track meets. I have to thank my coach, George Michaelides, because my school did not put money into track. Money was put into football and basketball, but nothing into track. That meant that we ran some indoor meets, but not the quality ones. My coach knew the coach of a private school, Pingry High School. I would go to big indoor meets with them and run unattached. That gave me more opportunities to race. By April I had run some quality races. In the first race outdoors, I broke the State Record with a forty-eight point at a dual meet. I ran forty-six point six on cinders that was hand timed. My first meet against Vince Matthews was a dual meet. I went to the Eastern Championships and ran forty-seven point in my second meet against Vince Matthews. At the State Championships I ran forty-six point.

|

|

| GCR: |

What were the primary principles that Coach George Michaelides used at Thomas Jefferson High School to guide you and what were the main tenets of your training?

|

| RF |

He was a motivator. He came out of Georgetown as an 800-meter runner. His main course of training was three hundred meters. He had me race those three hundred meters. He put people in front of me to catch. He would tell them, ‘Go stand a way down the track and when Ron gets to within five meters of you start running – Boom!’ The warmup was very heavy with him. He would also break the race down into one hundred meters at a time and have us focus on racing each one hundred meters.

|

|

| GCR: |

You won the 1965 New Jersey Group 4 in 46.9 after your 46.7 in qualifying broke the meet record of 48.1 set by Harley Morris of Haddon Heights in 1963. Did the four guys behind you in the final, Duval Moore of Asbury Park, Hardge Davis of Montclair, Bob Dickson of Scotch Plains and Davis Morton of Ridgewood push you at all or were you off the front racing the clock?

|

| RF |

Back in the day I was very concerned with Duval Moore and Hardge Davis. We all became very close friends. I was ahead of them off the turn. Even though I was a 400-meter guy, I was undefeated in the one hundred meters and two hundred meters in dual meets.

|

|

| GCR: |

At the 1965 Golden West Invitational, your winning time of 46.8 broke that meet record of 47.0 set by Fred Banks in 1964, but you had three strong opponents in Ken Head of New Albany, Indiana in 47.3, Conley Brown of Houston, Texas in 47.7. and L.J. Cohen of Corpus Christi, Texas also in 47.7 seconds. Were you out fast and what were the key points in that race that led to your victory?

|

| RF |

Coach Michaelides set that up and the school did pay for me to go out to the race. I was ranked number one in the country and Lee Evans was ranked number two in the country. My race plan was just to run. With the stagger starts, I just took it out and ran. When Lee Evans didn’t show up, my main concern was Kenny Head. I know that, if Lee were there, he would have been my main challenger. He was the one I kept my eyes on and my mind geared up to beat. I had to beat him. I don’t think I noticed who was ahead because I hadn’t run that many stagger start races in my life. That’s why my coach said, ‘Go from the gun.’

|

|

| GCR: |

In high school, did you race against your future Olympic teammate Larry James of White Plains High School in Westchester, New York?

|

| RF |

No, I didn’t run against Larry until my junior year in college.

|

|

| GCR: |

What other races stand out from your high school competitions at the Armory, Randall’s Island, or other venues?

|

| RF |

There were races indoors in New Jersey and I would catch people from the back. But I was just getting in shape and the races weren’t anything big.

|

|

| GCR: |

COLLEGIATE COMPETITION What colleges recruited you, did you narrow your choice to a few and why did you decide to attend Arizona State University?

|

| RF |

I had at least two hundred scholarship offers. With a 46.6 time for 440 yards, everyone wanted me. Air Force, Army, New Mexico, UCLA, USC – they all came after me. I wanted to go to San Jose State. I didn’t know anything about going to college because I was the first in my family to go. So, I didn’t get any support. The coach mentioned a couple of colleges. Somehow my uncle mentioned San Jose State and that stuck with me when I was planning to go to college. I called San Jose State and got the assistant coach. I said, ‘Coach, it’s Ron Freeman, 46.6 for 440 yards, how are you doing? I’d like to go to your university.’ He said, ‘Okay, but you’re going to have to pay.’ I told him I didn’t have any money and asked him why. ‘Because you’re out of state.’ I couldn’t pay. This was before Lee Evans, John Carlos and Tommie Smith went there. A guy named Ron Davis was there. If they had given me a scholarship, I would have been at San Jose State. When I visited Arizona State, it seemed like a good fit. The coach had sent me a picture of Ulis Williams and Henry Carr. It was a good fit academically for me in political science and psychology. I looked at UCLA and USC, but they were too big, and the campuses were too spread out. Villanova was an all-boys college, and I came from an all-boys high school. They had a good coach and program, but I didn’t want that. I also wanted to go to warm weather, and, in my mind, I wanted to go out west. When I ran 48 seconds, I was contacted right away and got a scholarship offer from an HBCU, Virginia State University. That was my first scholarship offer and I considered going there. When I ran the 46.6, everything went to another level. I am kind of sorry I didn’t go to Virginia State. But I wanted to go west at that time.

|

|

| GCR: |

I can probably relate to your transition to college as I came out of high school in Miami and went to Appalachian State in the North Carolina mountains, was a long way from home, and didn’t even go home until Christmas. How was it for you transitioning to college at Arizona State athletically, academically and being away from your home across the country?

|

| RF |

It bothered me that first year. I was homesick, but after that year everything was okay.

|

|

| GCR: |

How did Coach Baldy Castillo and his assistant coaches help you grow as a runner and person and what were the main points of their training system regarding endurance and speed compared to what Coach Michaelides had you doing in high school?

|

| RF |

It was a good program, but I was on my own to develop my workouts. I was in a phase where I worked out alone a lot. I was designing my own workout program and it may not have been the best. There were people I should have gone to, but I didn’t. The key person was Tom Hester who would have been my workout partner who would have changed my whole life at Arizona State. But, as soon as I got to school in August for my freshman year, he died in a car accident. That made it hard as he would have been like training with Lee Evans. What Baldy Castillo did when he was coaching is he would put us in the top competitions that we could race in so we would have to race ourselves into shape and I do appreciate that. He put us in the big time. Our conference was big time, and he gave us exposure.

|

|

| GCR: |

You won individual Western Athletic Conference Championships at 440 yards three straight years from 1966 to 1968. Were any of these races memorable for tight competition or coming from behind?

|

| RF |

We had New Mexico, Utah, Arizona, Wyoming and Brigham Young and other good teams, so I was always pushed.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned that Coach Castillo took your team to big competitions. What other meets, such as the California Relays, Mt. SAC Relays and Modesto Relays did you race while at Arizona State and are there some individual races or relays that are in the forefront of your mind from those years?

|

| RF |

We went to Mt. SAC, and I hooked up on the anchor leg of the relay with Lee Evans and Larry James and we took third place. That was a memorable race.

|

|

| GCR: |

How much fun was it competing at the WAC Championships, cheering your teammates, and helping your team to two third place and one second place finishes?

|

| RF |

It was a rewarding time. It was an exciting time.

|

|

| GCR: |

At the 1968 NCAA Championships, the 440-yard dash was a prelude to the Olympic Trials as Lee Evans won in 45.0, and Larry James nipped you for second place as you both were timed in 45.4 seconds. What were the crunch points in that race as the three of you raced for the win?

|

| RF |

It was close and I couldn’t do anything about that as I knew it was going to be challenging. It came out like it came out. For that race, I had just turned twenty-one years old, and that race was held on my birthday.

|

|

| GCR: |

WRAPUP AND FINAL THOUGHTS After your NCAA eligibility was finished, the 1968 Olympics were in your rear-view mirror, and there wasn’t today’s option of running professionally, what was your thought process regarding continuing to focus on competing versus moving toward further education, working and the next phase of your life?

|

| RF |

At that time, I had a child and moved back to New Jersey. I tried to train, but I just couldn’t train. I couldn’t find a good indoor facility and I didn’t like running in the cold. I tried to but just couldn’t. That ended my future competition dreams. Lee Evans talked to me a couple times, but I couldn’t. I also had to get a job.

|

|

| GCR: |

You have worked quite a bit with young people in the States and overseas and sometimes the success of those we coach is more rewarding than our own success. How exciting has it been to watch the success of those you have coached and what are primary similarities and differences in motivating yourself versus others?

|

| RF |

Whether I coach or work as a humanitarian, I’m always excited to see people I’ve touched, talked with and given information to and how they grow. I’ve been doing this ever since I was running track by coaching and working with youth in the U.S. and in Guinea and in Zambia. It is based on my experience and my exposure and my growth. I show people diverse ways to look at how they can improve or better themselves. I am always happy to see when people take a piece of information I give them to better themselves. I feel very upset if I give people information that I think is good and they don’t strive to better themselves. It makes me feel like maybe I didn’t give it to them the right way or maybe they didn’t want it. I’ve done this with my children by giving them advice when they were growing up. They’ve taken it, run with it and they’ve grown. That is why I try to give others useful information about Africa. They may have received valuable information, but not from the same experience that I have. People also may not talk to a poor youngster. In Africa, there are children growing up who are much better off than I was as a child and there are others who don’t have that situation. I will give my information to all kids. It is very rewarding to give a poor youngster or middle-class youngster some things to think about so they can grow. They may be a track athlete or students in school.

|

|

| GCR: |

In line with that thought, what advice do you give to youth and teenagers so that they can be their best and reach their potential as human beings with the gifts they have been given that all comes together in the ‘Ron Freeman philosophy?’

|

| RF |

The one thing I saw out of the years I was in track and field and the years of just playing sports is that sports are a microcosm of life. You learn how to win. You learn how to lose. You learn how to be at work on time. You learn teamwork. You learn so much by playing sports and being involved in recreational activities. I take all those instances and I talk about those experiences with youth in my lectures. What is a winner? What is being successful? How do you dream about being a winner? How do you think about being the best you can be? I take all those models that I used growing up and I give that information to youth. I also give that knowledge to adults. I do this because, over the years, I’ve had people help me. Ron Freeman didn’t make it by himself. Ron Freeman was a part of a team of people that came to him. They made suggestions to me on what I could do and how I could do things better. I’m just passing that information along to young folks. In many countries people don’t talk about how they can be better and so I discuss this knowledge. How can you get a job? What is the best way to put a resume together? How can you be a team player? Those are some of the skills I learned through the years to make me as successful as I am as a humanitarian.

|

|

| GCR: |

In August 2017, you received the Athletes in Excellence Award from The Foundation for Global Sports Development in recognition of your community service efforts and work with youth. Was this both humbling and rewarding to receive this award and others for the decades you have served others?

|

| RF |

In particular, since it came from The Foundation for Global Sports Development, it was humbling to be appreciated and to have them recognize me. It is a great organization. I felt good then and still feel good about that recognition. It motivated me to continue doing what I had been doing. Another award I received in 2015 was the JOPPO Humanitarian Award. That is an international non-government organization that provides Olympic coaches and Olympic groups. Their conference is very large with as many as three thousand attendees. I received the award for the programs I was doing in Africa. When you are recognized, it makes you feel that you are meaningful. But I did programs to do them and not for recognition. One group that has given me much support is the U.S. Olympians Association with Cindy Stenner. She would always give us T-shirts or caps or whatever we needed. They helped for many years that IMA was in operation, whether it was an after-school program in the U.S. or a project in Africa or somewhere around the world. That is what the Olympic family does. Also, the International Olympic Committee funded our programs through UNESCO. So, this Olympic family is a very good family. They support many Olympians, and I am proud I am one of those they have reached out and touched.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned that one reason you live in Zambia is their health care system, especially since you are now seventy-five years old. How is your current health and what do you do for fitness?

|

| RF |

I eat certain foods and try to watch what I eat. There is a small fitness center where I live so I get on the treadmill and the bike. I lift light weights – nothing heavy. And I walk a lot.

|

|

| GCR: |

What are some of your goals for the future in terms of personal development, continuing to help others, travel and do you see yourself slowing down or doing as much as you can?

|

| RF |

I’ve done a lot of traveling in my life. However, I do want to take a lot of trips here in Zambia because it is such a beautiful country with so much to offer. I just can’t say enough about Zambia. Tourists should flock here. Many of my friends have told me they are coming to visit. The untold story of Africa is Zambia. There has never been a conflict. The people are nice. The food is great. There is so much to see. So, I plan to take some time to see Zambia. At the same time, Tanzania is also an outstanding country. If you go through Zambia, Tanzania, Kenya and Botswana – there is so much to see in this region. I have always liked Paris. My favorite country where I have spent a lot of time is Greece. I was a consultant to Greece during the time they were bidding on the Olympic Games and still have some good friends in Greece. I plan to hit some of those countries but right now I want to get to know Zambia. I am also working with a program that frequently takes me to Nigeria. That is another home for me. Why Nigeria? A group of us have gotten together and we plan to host the Lee Evans Memorial Track and Field Meet in November, from the 21st to the 26th. That has been rewarding putting that together. The key attribute about the competition is we are bringing a group of kids from the United States and a group from Trinidad and Tobago. We will try to get some kids from Zambia there. We are hopeful these kids will get exposed to Nigeria and to Africa and it will be more than a simple track and field meet. There will be history involved. There will be a tour and the kids will intermingle with kids from Nigeria. It will be an annual event. That will be a big undertaking for me to promote that initiative in Africa. There is another initiative I am working on in Nigeria and that is Festac. The first Festac program was held in Nigeria in 1976. That is going to be a major Pan-African event that we hope to conduct within the next few years. It is in the discussion stages now and we have had three or four meetings about it in Nigeria. That will keep me motivated. Other than those activities, I want to spend more time with my grandkids, and I will this year. There is Tyler, who is a young man, and Ann-Marie and Noah that are two years old and several months old. I also want to spend my time doing work here in Zambia, doing work in Nigeria and supporting the Olympic movement any time I can.

|

|

| GCR: |

When people think of Ron Freeman now, and after you are gone when people think of Ron Freeman, what do you want them to think of in terms of your legacy or what you have done for humanity?

|

| RF |

I want people to think that I was a good guy, that I reached out to and touched thousands of youths and adults. I hope I have left some people behind to continue what I have done and that is the main thing. I want what I have done to be continued on. I am trying to leave a team that will follow in my footsteps to do what I have done. I have a group doing that in Guinea. I have a group doing that in Mali and I hope to do that here in Zambia.

|

|

| |

Inside Stuff |

| Hobbies/Interests |

During my time in Africa, I have enjoyed fishing, though I don’t fish much anymore. One of my interests for many years was going on vacations and travelling

|

| Nicknames |

The only nickname would be ‘Ronnie.’ That is what I was called when I was growing up. When I went to Arizona State, they chopped it down to ‘Ron’

|

| Favorite movies |

A movie that I watch a lot is ‘Chariots of Fire.’ I like ‘Django Unchained’

|

| Favorite TV shows |

I watch a lot of mystery shows, but don’t have any special series

|

| Favorite music |

I like Zambian music. I like African music. I’m old school. I always go back to ‘The Temptations’ and ‘Smokey Robinson.’ Though my favorite genre of music is jazz, I go back to my old school rock and roll because it brings back memories. I do listen to a wide variety of music. I don’t understand this rap music, though it is cool, as I’m old school. When I’m walking on the treadmill, I turn on my stereo and keep moving for fifteen minutes

|

| Favorite books |

I love reading books about Olympians that I know. I like reading books by Mel Pender, John Carlos, Wyomia Tyus, Lee Evans and Vince Matthews. I read them over and over. They are people I know and that were exciting in my life. Mel Pender is the ‘Audie Murphy’ of our time, and most people don’t know that. I’m amazed by Mel because he jumped out of planes in the service and made it to two Olympic Games in between. If you came out of war and went to a training camp, you would be shell-shocked every time you heard a siren. But Mel came out of serving and did it at his age. There are also some books on African history I like to read. There is one book I love to read that one of my college roommates, one of my oldest friends I’ve known since I was seventeen, and I talk about. If anyone wants to get an informative book, it’s called ‘The Mind Factory.’ It’s so heavy that there is another book called, ‘I Am A Key’ that explains how to read ‘The Mind Factory.’ These two books I read often, and they aren’t simple reading. ‘The Mind Factory’ is about cyphering information and it is amazing to be a cypher. One of my friends, Larry Odell Johnson, is the author and one of the top cyphers in the world. Both books are available on Amazon

|

| First car |

It was a Pontiac

|

| Current car |

I have no car. I have a driver

|

| First Jobs |

My father was good at giving me the will to work and teaching me how important it was to work. When I was about seven years old, I used to walk about a half an hour from uptown to downtown. I would sell shopping bags. I learned how to buy three for a dime and sell them for more. By the end of the day, I could have about three dollars and use it for a movie and to buy hotdogs. Then I went down to the same markets and helped with killing chickens at the chicken market. Next I started selling eggs. I would also collect newspapers, bring them home and store them. My dad would pack them into the car, and I would take them to sell for money. At one time I was washing cars for a friend of my dad’s at a car wash. As I grew up, my dad turned me on to some people that needed their yards cut and I started cutting grass. I also shoveled snow, which kids don’t do today. I made a lot of money shoveling snow. Nowadays, kids want a hundred dollars to shovel snow. My father and mother were very important role models on the way we should work, and I am very fond of that

|

| Parents |