|

|

|

garycohenrunning.com

garycohenrunning.com

be healthy • get more fit • race faster

| |

|

"All in a Day’s Run" is for competitive runners,

fitness enthusiasts and anyone who needs a "spark" to get healthier by increasing exercise and eating more nutritionally.

Click here for more info or to order

This is what the running elite has to say about "All in a Day's Run":

"Gary's experiences and thoughts are very entertaining, all levels of

runners can relate to them."

Brian Sell — 2008 U.S. Olympic Marathoner

"Each of Gary's essays is a short read with great information on training,

racing and nutrition."

Dave McGillivray — Boston Marathon Race Director

|

|

|

|

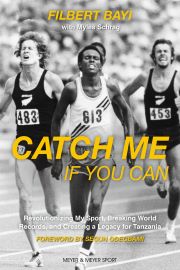

Filbert Bayi is considered the most legendary athlete from Tanzania of all time. He is the 1974 Commonwealth Games Gold Medalist in the 1,500 meters in a World Record of 3:32.16 as the top five finishers were amongst the seven fastest in history to that date. Filbert also won the mile in a World Record of 3:51.0 at the 1975 Martin Luther King, Jr. Games. Both World Records were previously held by Jim Ryun. He also earned a 1980 Olympic Silver Medal in the 3,000-meter steeplechase in 8:12.48. At the 1973 All-Africa Games, Bayi raced to the Gold Medal as he beat Kipchoge Keino. He defended his Gold Medal at the 1978 All-Africa Games. The two-time Olympian carried the Tanzanian flag at the 1980 Moscow Olympics Opening Ceremonies. Filbert’s road-racing wins include 1984 Peachtree 10k, 1984 Cleveland Revco 10k and 1984 Grand Prix of Bern, Switzerland 10-mile. His limited marathon racing includes the 1986 Honolulu Marathon where he finished fourth in 2:16:16. Filbert’s front-running racing style is noted in the title of his 2022 autobiography, ‘Catch Me if You Can.’ Personal best times are: 800 meters – 1:45.32; 1,000m – 2:18.1; 1,500m – 3:32.2; Mile = 3:51.0; 2,000m – 4:59.21; 3,000m – 7:39.27; 3,000m steeplechase – 8:12.48; 2-mile – 8:19.45; 5,000m – 13:18.2; 10-miles – 47:14 and marathon – 2:16:16. Bayi and his late wife, Anna, formed the Filbert Bayi Foundation, Schools, Health Center and Sports Center in Tanzania to give back to the community. He is Secretary-General of the Tanzanian Olympic Committee. Filbert was very generous to spend an hour and twenty minutes on the telephone from Tanzania for this interview.

|

|

| GCR: |

THE BIG PICTURE It’s been fifty years since you won the Gold Medal in the 1,500 meters at the 1974 Commonwealth Games and nearly as long since you won the 1975 ‘Dream Mile’ at the Martin Luther King, Jr. International Games, both breaking Jim Ryun’s World Records. What did it mean in the moment on those days to beat strong fields and to become the fastest man in history and how did those moments have a lasting impact on your life?

|

| FB |

Like you said, it is fifty years to this Golden Anniversary of the 1974 Commonwealth Games. That race in 1974 is one that I still watch on video on YouTube and it takes me back. I look young as I was in those days. I love to watch it every time and it is hard to believe what happened. I wasn’t rated to be a winner in that race. John Walker was the native there in New Zealand and all the credit went to his name. Everybody knew he was going to win the race because it was on his soil. The belief was that we athletes from other countries were there to escort him to break the record and win the Gold Medal. That race is still in my mind. John Walker and I still meet each other but, unfortunately, the other medalist, Ben Jipcho from Kenya, died a few years ago. Mike Boit and Rod Dixon were great that day and every time any of us meet we are like family because that day made us all.

|

|

| GCR: |

The 1974 Commonwealth Games 1,500 meters resulted in five of the top seven times in history at that point and had a stellar field as strong as any Olympic final with Ben Jipcho, John Walker, Mike Boit, Rod Dixon, Suleiman Nyambui, Graham Crouch, and Brendan Foster. How confident were you heading into that race, what was your strategy as you were on the starting line and can you take us through key points as you raced to victory and a World Record?

|

| FB |

The New Zealand team was very strong and both John Walker and Rod Dixon were good sprinters at the end of a race. Usually, I am also very good at the end. My strategy was to go out fast and then, if they were close to me at the end, I could decide what I wanted to do since I would be leading. So, my strategy was to run like that and whatever happens would happen. I could win or I could lose, but I didn’t care. Maybe on that day it would turn out good and it did as I won the race. Nobody thought I would run like that, and they probably thought I would die with two laps to go or one lap to go. If you watch the video, with one lap to go I had a good lead. At two hundred meters to go, I looked back and they were killing themselves to catch me. I could see the distance from me to the chasing team had decreased from a lap to go until two hundred meters to go. I knew they were pushing themselves and I relaxed. I was imagining that at fifty meters I would kick with all I had and, if anybody was close to me, nobody could catch me. That is what happened to John Walker. When he was close to me, I accelerated and put more stress on myself. I thought, ‘Let it be, ‘and then the race was over.

|

|

| GCR: |

Can you describe your feelings and emotions as you, John Walker and Ben Jipcho received your medals and stood on the podium just like at the Olympics as the Tanzanian National Anthem was played and your flag was raised?

|

| FB |

When I heard my National Anthem and saw my flag raised on top of the other flags, I thought of the years of training, and this is what was happening, and it was the payoff.

|

|

| GCR: |

Now everyone knew who you were and how you could run strong from the front. Fifteen months later you toed the line at the 1975 Martin Luther King, Jr. International Games with Ireland’s Eamonn Coghlan and four strong Americans – Marty Liquori, Tony Waldrop, Reggie McAfee, and Rick Wohlhuter. How did that competition compare to the previous year’s Commonwealth Games since your foes knew of your propensity to lead? And can you take us through that race as it unfolded, and you were able to emerge victorious?

|

| FB |

Rick Wohlhuter and Eamonn Coghlan were sharing their pace behind me. They were working together to try to beat me. When I discovered this was their strategy, I had to save some of my strength. Eamonn Coghlan was close to me at the straightaway and then he faded. The American, Marty Liquori, came from behind him and chased me. He tried to chase me, and I knew it was time to go. I accelerated and he didn’t follow, and I finished first. Those guys were the ones who made my day. If they didn’t chase me, I wouldn’t have broken the World Record.

|

|

| GCR: |

That is true as you only broke Jim Ryun’s World Record Mile of 3:51.1 by one tenth of a second with your 3:51.0 clocking. That is as close as it could be.

|

| FB |

I appreciate them. Even when I meet them now, I tell them that they made my day. I met with Jim Ryun and Eamonn Coghlan in 2019 at a reunion in Monaco and it was very good to meet with middle distance alumni.

|

|

| GCR: |

Just as you have inspired others by your performances, who are the athletes who inspired you when you were starting out running and becoming interested racing in track and field competitions?

|

| FB |

Definitely the man I call my father, Kipchoge Keino. From Kenya. He was the one. When I went to the Olympic Games for the first time in 1972, it was his third Olympics and very normal for him. But I was very young at that time. I ran with him in the heats of the 1,500 meters and in the steeplechase. I admire him because, when I was running outside of lane one because I was afraid of being hit or being spiked, he would shout at me, ‘Go inside in the first lane! Go inside.’ He was helping me. I think he knew that I was a young man and maybe one day I could take these lessons from him.

|

|

| GCR: |

How was it racing in the 1973 African Games 1,500 meters in Lagos, Nigeria with Kip Keino as you were able to win the 1,500 meters?

|

| FB |

In Lagos, Nigeria, my teacher, Kipchoge Keino, lost to me. He was second to me and that was the last time he raced with me because he turned professional with the International Track Association.

|

|

| GCR: |

There wasn’t an opportunity for you to compete in the 1976 Olympics as over two dozen African countries boycotted due to a rugby team from New Zealand playing in South Africa, a country which practiced apartheid. How disappointing was it not to compete in Montreal, did the boycott achieve its goal, was it necessary in your opinion, and what are similarities and differences to the USA-led boycott four years later of the Moscow Olympics?

|

| FB |

I was disappointed in a way since I had trained for four years since the Munich Olympics to try and get an Olympic Medal. I knew two months before the Montreal Olympics that I was ready because I won a 1,500-meter race in Zanzibar in 3:34 and that was the fastest time for anyone going into the Olympic Games. I knew that, if I went to the Olympics Games, I could win the first Gold Medal for my country and maybe set the record. The announcement came from the head of state in Mauritius that African countries should boycott and not participate in the Olympic Games because of the New Zealand rugby team going to South Africa, a country that was not a member of the International Olympic Committee because of the practice of apartheid in their country. It was very disappointing, but we had to think of the human beings in South Africa. There were the killings in Soweto, and they happened when the Montreal Games were approaching. African countries wanted New Zealand to not participate in the Olympic Games. The IOC allowed New Zealand to participate, and the African countries boycotted. We had to support our brothers in South Africa, especially those in Soweto. There was pain for us athletes but, we are all humans, and we have to support others.

|

|

| GCR: |

In the mile and 1,500 meters, Jim Ryun and Kip Keino were past their peak years as you burst into prominence in the mid-1970s along with competitors we have mentioned such as John Walker, Rick Wohlhuter, Ben Jipcho, Rod Dixon, and Suleiman Nyambui. Then runners like Steve Ovett, Steve Cram and Sebastian Coe arrived on the scene and surpassed you and your foes as they asserted themselves as the top racers at the middle distances. When you are racing with the best in the world, winning races and setting records it may seem like this can continue for a lengthy number of years. How difficult is it to stay on top for a long time when there are young, hungry competitors working to be their best and the best?

|

| FB |

In the 1960s, Jim Ryun and Kipchoge Keino were known for the 1,500 meters and mile. In the 1970s, it was John Walker. At the end of the 1970s and into the 1980s, the guys were David Moorcroft, Steve Ovett, and Sebastian Coe in Moscow. Afterwards, it was Dave Moorcroft, Sebastian Coe, and others. Then Algerians and Moroccans rose to the top. There were always some new guys coming along. In 1980, I was getting old while Steve Ovett and Sebastian Coe were young. It’s the same as in 1973 when Kipchoge Keino and Jim Ryun were old as I was young, and I was coming up. I was learning and taking from them. I’m sure it was the same as Ryun and Keino took from the Frenchman, Michel Jazy. And so, it is like a relay.

|

|

| GCR: |

At the 1980 Moscow Olympics, you switched gears like Kipchoge Keino did later in his running career and competed in the 3,000-meter steeplechase. Can you relate how your race results earlier that year influenced you to focus on the steeplechase, your strategy in the race, and key points as you led most of the way before Poland’s Bronislaw Malinowski passed you on the last lap and you earned the Silver Medal with a Tanzanian National Record?

|

| FB |

My coach, Ron Davis, and I were together at that time and Ron told me that, if I wanted to change to the steeplechase, I had to run 8:20 in one of the races. I ran races in Stockholm and other cities with Malinowski from Poland and Tura from Ethiopia. In one race I ran 8:18 and I beat Malinowski. So, I knew that I would now go to the Olympic Games in Moscow and do the steeplechase. If we go back and watch the Olympic race in Moscow, we can see that I could have won that race. But I think I miscalculated my strategy and I lost. At the last water jump, as we were headed toward the finish, Malinowski caught me there. When he caught me, I was unable to recover. When somebody comes from behind and catches you, all your strength disappears. Malinowski was coming very fast. The Ethiopian was trying to catch me, but I knew I could hold him off.

|

|

| GCR: |

You were primed for strong medal contention at the 1984 Olympics but were sidelined by shin splints and couldn’t compete. How tough was it to watch those Games as the medalists all ran times that were within your capabilities?

|

| FB |

I paid that year because I ran many road races. In 1984 I ran several road races – The Revco 10k in Cleveland, the Peachtree 10k in Atlanta and a 10-mile race in Switzerland. I think going from track to road racing, my muscles and my bones were overloaded. After being overloaded, I broke down because we are human beings. We are not machines. The load I put on myself was so extensive. I had shin splints, and I couldn’t sprint because it was so painful. I went to the Olympic Village and was training on the UCLA campus. I was monitored by my coach and doctors. One week before the steeplechase, I announced that I was pulling out while we were already in the village.

|

|

| GCR: |

The road races you ran included some tough and demanding courses. You had notable victories at the 1984 Revco 10k in Cleveland in 28:27 and Peachtree 10k in Atlanta in 28:35, seven seconds ahead of Ashley Johnson. What are your takeaways from winning these prestigious races, especially in Atlanta with the summer heat and the hills in the last three kilometers and then also racing the hilly Elby’s 20k in West Virginia?

|

| FB |

Peachtree was downhill in the beginning and the end. Elby’s was a very tough course.

|

|

| GCR: |

In both 1973 and 1978, you raced to Gold Medals at the All-Africa Games at 1,500 meters. How exciting was it to represent Tanzania at these Games and to bring home Gold Medals for your country?

|

| FB |

In 1973 we talked about how exciting it was to win and to be ahead of Kipchoge Keino. In 1978, after I won, it was disappointing to go the Commonwealth Games and be beaten by David Moorcroft. After we ran the All-African games, we went straight to the Commonwealth Games. So, I thought I would come home with two Gold Medals.

|

|

| GCR: |

The 1978 Commonwealth Games 1,500 meters was very close as David Moorcroft ran 3:35.48, just ahead of you at 3:35.59, followed a hundredth of a second later by John Robson at 3:35.60 with Francis Clement fourth at 3:35.66 Wasn’t that an extremely strong finish for the four of you within two meters at the end with you leading, Moorcroft and Robson on the outside and Clement on the inside?

|

| FB |

In Edmonton, I did all the work and David Moorcroft came on to catch me at the end. Unfortunately, David Moorcroft put a mark to beat me.

|

|

| GCR: |

In the 1970s and early 1980s, Tanzania had a group of World class athletes from the middle distances to the marathon including Gidamis Shahanga, Juma Ikangaa, Suleiman Nyambui, Zac Barie, and you. In the past few decades this hasn’t been sustained. What is the outlook for Tanzania producing more athletes who can compete on the world stage?

|

| FB |

I am surprised because in the 1970s and early 1980s there was no money when we were running. Now we do have a few top runners like Gabriel Geay, Alphonce Simbu, Magdalena Shauri, and Failuna Matanga. Since there is money in racing, I thought we would be more like Kenya and Ethiopia. But in Tanzania there are few top athletes. Maybe we lack coaches. I don’t see that we have coaching for kids because it is expensive to have a team of just five or ten kids. In Kenya, there are so many professional athletes that they help the young kids. Here we only have a few professional athletes.

|

|

| GCR: |

I met two of your Tanzanian countrymen when I was an invited runner at the 1982 Montreal Marathon. I met Leadgar Martin and Emmanuel Ndmanodo who came in fourth and seventh place. One of them pinned a Tanzanian Olympic pin on my shirt and made me an honorary Tanzanian. Were these great runners and nice young men friends of yours?

|

| FB |

Those guys were my work mates. Emmanuel was with me in the army. Leadgar Martin and I ran together, and we went to school together in America.

|

|

| GCR: |

An exciting portion of your ‘Catch Me If You Can’ biography is that after retiring from competitive running, you and your wife, Anna, slowly built the Filbert Bayi Schools which started with less than ten children and now educate over one thousand students. How important is it to utilize your visibility and credibility to help others and to be an ambassador for track and field and for education in your country?

|

| FB |

I went to America for schooling, graduated and felt that I needed to go back to Tanzania and invest in education and serve my fellow Tanzanians. My late wife was a national player in net ball. After we were married, our first kids were sent to Kenya for education. We asked ourselves why we and so many other Tanzanians were sending kids to Kenya to be educated. We decided that we could build a private school and use the English method of teaching. Some kids that had been going to Nairobi in Kenya came to our school. We started with very few kids – only seven or eight. The numbers increased and, in two years, we had one hundred plus. At that time, we had a teacher from Kenya. Parents brought their kids because Kenyan schools were taught in English and Tanzanian schools were taught in Swahili. If we had Kenyan teachers, the kids would come. We managed to have a school in Dar es Salaam and Kibaha. The school in Dar es Salaam was in a small area. The school was big, but we couldn’t build sports fields because the land was too small. That is why we started in Kibaha which is 35 to 40 kilometers away. We bought a big area and built a secondary school. At the secondary school we established a program in netball since my wife was the President of the Netball Federation of Tanzania. We gave scholarships to talented girls in the sport and had a very talented team in netball. We won the national championships twice. Then my wife retired. Our aim was to take the best athletes overseas to play professionally, but they kept them playing in the country. So, we dismantled the netball team at our school and started an athletics program. We gave scholarships to young people from our primary schools that we scouted and gave them a secondary education for free. The poor parents couldn’t afford school for their children, so we gave them a scholarship which was worth one thousand and five hundred dollars a year. We gave them uniforms, sports equipment, shoes, and everything they needed. Many were able to go to school at American universities and be taught by high performance coaches. We have one young woman, Regina Miyachi, who is running now at the University of Northern Colorado, and she is doing very well. She just ran a 2:05 and a 2:04 for 800 meters after leaving Tanzania with a best time of 2:08. She is getting her times down and is in her second year there.

|

|

| GCR: |

FORMATIVE YEARS. EARLY RUNNING AND COMPETITION Everyone starts somewhere and in what sports did you take part as a youth? Were you playing soccer or running or doing other activities that kept you fit as a youth and teenager?

|

| FB |

I started sports when I was very young. I was jumping, playing basketball, and playing volleyball. I even improvised the pole vault with a stick. When I was older, I was on the Army soccer team at the Armed Forces Air Transport as a goalkeeper. I was also playing as number eight. Finally, when I was playing number eight, a teammate would pass me the ball and I would advance down the field to score a goal. People wanted me to be a footballer but, prior to the 1972 Olympic Games, I realized that there were no rules to guide us. Sometimes when I was the goalkeeper and received a ball, I would have to raise my knees up to avoid being injured. I thought I would have to find another way. I wanted to do my own sport and thought that the better way was running so I started to be an athlete.

|

|

| GCR: |

Was anyone coaching you and what were you doing in training as you raced a 1:55.0 for second place at an Armed Forces meet in Zanzibar in 1970?

|

| FB |

It was just a love of sports. There was no real coach at that time. The coach in the army would take the stopwatch and time me for a distance ten times. He would plan for me to go to meets. The runners had to do it for themselves.

|

|

| GCR: |

Going back before your army days, how tough was it at the regional meets when you faced Alexander Stephen Akwhari, younger brother of Olympic marathoner John Stephen Akwhari, in the mile and half mile?

|

| FB |

That was in 1967 and 1968. He was in the top of 1,500 meter and 5,000-meter races.

|

|

| GCR: |

How much did Alexander’s older brother, Olympic marathoner John Stephen Akwhari, inspire you as a teenager?

|

| FB |

He was a nice man and helped us as young men. I was close to their family. When I went to Kumburu, I would always spend the night with their family including Alexander and his sister. We knew each other very well.

|

|

| GCR: |

After you joined the army at age seventeen, how did the discipline needed to succeed as an aircraft mechanic parallel the structure and consistency necessary to be a strong runner?

|

| FB |

I believe in having discipline. If we have self-discipline, nothing will fail. Athletes feel that our performances will be helped by the coach or someone else, but it is mostly on ourselves. I believe in that.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned earlier about running in the 1972 Munich Olympics, but how terrible was it when terrorists took hostages, eventually killing them? Did that ruin the excitement of being in the Olympics?

|

| FB |

The first experience I had was that morning as our quarters were close to the Israelis. There was almost no security in the Olympic Village. We could move around freely. That morning, I was going for my morning training, and I saw people with socks on their heads. I passed that way. When I came back from training, I saw helicopters going over the building and I didn’t know what was going on. I was a young man at that time. We could see people on the second floor or third floor going around with guns. I went to my room. After a few minutes as we watched the helicopters going around and around, people were saying that something was happening in that building. They told us to stay away from that building and to remain in our rooms. Then the news came out that they were terrorists who had kidnapped the Israelis. In the previous Olympics, there was nothing like this. We didn’t know what was going on, but the Games continued.

|

|

| GCR: |

Though you didn’t have much coaching until this point, after the Olympics, how helpful was it having Erasto Zambi and East Germany’s Werner Kramer help set up a workout schedule and coach you and what were some key training philosophies and workouts that aided you then and in future years?

|

| FB |

That was in 1973 and 1974. Werner Kramer helped me in 1973, but then he left. We were communicating but, since he was from East Germany, I don’t know what happened. Erasto Zambi was at the University of Dar-es-Salaam, and he was also assisting me. At the university track, he would give me advice though he wasn’t coaching me. He would give me times with the stopwatch but didn’t give me a training program like the German, Werner Kramer.

|

|

| GCR: |

OTHER IMPORTANT RACES Many people think you came out of nowhere when you set your World Records in 1974. But if we look at four of your 1,500-meter races in a three-week period in 1973 from mid-June to late-June, you won at Stockholm in 3:37.9, at Warsaw in 3:37.9 at Aarhus, Denmark in 3:35.6, and at the Helsinki World Games in 3:34.6, before Ben Jipcho outkicked you in the Stockholm mile 3:52.00 to 3:52.86. Did those three weeks tell you that you could run with anyone in the world?

|

| FB |

We trained hard. I tease my Tanzanian young athletes now when I have them watch videos of my races and I tell them how we used to train so we could race well. Kenyans and Ethiopians are training well now, but we don’t have the development and coaches in our country. We have a few elites, but not many young, good athletes. How did they become elites? There might be somebody who prepared them, but most of the top Tanzanian athletes are getting their advice from Kenyan coaches in their villages.

|

|

| GCR: |

A few months after your 1,500-meter World Record at the 1974 Commonwealth Games, in June at the Helsinki World Games you led in 52.9, 1:50.4, 2:50.4 before you faded as John Walker won in 3:33.89 with you timed in 3:37.2. Was that an off day, were you out too fast, or was that John Walker’s day?

|

| FB |

Every day is a different day. And anything can happen. Human beings sometimes get tired. We might have a slight weakness in our body. We are not machines and sometimes our bodies get tired or exhausted.

|

|

| GCR: |

You raced some great indoor miles including winning the Wanamaker mile in New York over Paul Cummings and Wilson Waigwa, the L.A. Times mile over John Walker, Rod Dixon, Byron Dyce and Steve Prefontaine and the San Diego ‘Jack in the Box’ mile over John Walker and Rick Wohlhuter. Did you enjoy the indoor racing with its tight turns and close fan experiences and why were you so successful in this new venture?

|

| FB |

In those days, indoor racing wasn’t like it is today. Now the tracks are 200 meters, while we raced back then on 160-yard tracks. We ran on boards, and I enjoyed that sound of bam, bam, bam, bam, bam, bam. It wasn’t easy. The mile was eleven laps then and it is eight laps now on a nice surface.

|

|

| GCR: |

In 1976 and 1977 you raced a variety of distances, including 800 meters, 1,500 meters, 3,000 meters and 5,000 meters. Did you like the challenge and different tactics and strategies used at these various distances while you also raced different competitors?

|

| FB |

I loved all distances, even the marathon. What I liked is all the distances helped each other. I ran the 800 meters as speed for the 1,500 meters. Then I ran 5,000 meters to get endurance and strength for 1,500 meters. My specialty was the 1,500 meters. I ran longer distances for a reason and shorter distances for a reason.

|

|

| GCR: |

In 1978 at Schaan, Liechtenstein you raced a distance that wasn’t raced often, 2,000 meters and won in 4:59.21. It was always exciting for fans for someone to break five minutes and to average under sixty seconds. Was that a neat distance to run because it took a different strategy to go an extra lap and to still try to average dunder sixty seconds?

|

| FB |

Everything is training. If we train hard, the adjustment is easy. I could adjust to any race distance. I trained so that any race distance in front of me didn’t matter. But, if your training isn’t one hundred percent, you start thinking of what you should do, but without confidence. When I was racing, I knew what I was doing. When I went to a race, I knew I was going to do it. I didn’t care about the time. I cared about winning. I would win a mile in 3:51, 3:52, 3:53 or 3:56, and that was normal. Sometimes I would win in over four minutes because of the weather or tactics of the race.

|

|

| GCR: |

After one of your bouts with malaria in 1979, Ron Davis coached you in 1980. What were key principles of his coaching and specific workouts that helped you to be so successful in your 1980 races up to and including the Olympics?

|

| FB |

Ron Davis was a coach. He was not a timekeeper. He was not the stopwatch guy. We worked together and he knew I was a hard-working guy. Whatever he told me, I did. He trusted me and we trusted each other. When we were in Tanzania and he wasn’t at a workout, he trusted me to do it. Sometimes he would come to a fartlek training, watch me, and supervise. I can say that he is my teacher, and he is everything.

|

|

| GCR: |

WRAPUP AND FINAL THOUGHTS You briefly mentioned that you raced marathons. When we review your marathon racing history, you ran the 1980 New York City Marathon in 2:20:34, 1985 Honolulu Marathon in 2:25:52 and 1987 Sydney Marathon in 2:22:07. There was one standout performance at the 1986 Honolulu Marathon where you finished in fourth place in 2:16:16 on a hot day. How did you find the marathon distance and was it exciting to race so strong that one time in Honolulu?

|

| FB |

In that 1986 race, I could have run even faster. I was running with Gidamis Shahanga. Ibraham Hussein and Zac Barie were very far in front of us as we were in third place. Shahanga was pulling me back and saying, ‘Don’t go like that. Don’t go faster. Let’s stay together.’ So, we slowed down. But he was planning to be number three because he had some techniques to beat me. We went down to Diamondhead and then to a park. Then he sprinted. I wasn’t experienced in the marathon and that was his technique to go and for me not to stay with him. After Diamondhead it was flat, but he was away.

|

|

| GCR: |

Track and Field has progressed in the past few decades with advanced coaching, shoes, nutrition, and pacemakers. Do you think that racing would have been much different, or that was just how the landscape was when you raced, you did all you could, and are you happy with your racing outcomes?

|

| FB |

There are so many reasons that we can’t compare those years with present days. In those times, we competed in athletics because of prestige. The good thing now is that there are incentives to race. So, it is quite different now. Sometimes I think that I was born in the wrong time. If I was born now, I may have been rich. But the time that I was born was okay because today, if I was rich, I may not have gone as far as I did. So, I am satisfied with what I have. I am satisfied with what happened to me. I have satisfaction in how I performed. Therefore, I was born in the right time. When I ran in those years, I was privileged to meet people who had self-discipline. I appreciate all of them. Since I was raised by my mother without a father, it was a good pleasure. The way I am today – I can’t blame anybody. I have done things in life for my people and for myself.

|

|

| GCR: |

It seems that all the fast, high-level distance races in recent memory have pacesetters. The only race I can think of that was raced like you raced is the 2012 London Olympics 800 meters when David Rudisha set the World Record of 1:40.91 and everyone was fast. Amos ran 1:41. Kitum, Solomon and Symmonds ran 1:42s. Aman, Kaki and Osagie ran 1:43. Rudisha ran a ‘Filbert Bayi race’ where he was out fast, broke the World Record and everyone ran great. Is that one of those races that you watched and thought, ‘That is a Filbert Bayi race?’

|

| FB |

I saw it in the videos and that is true.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned meeting with a special gathering of middle-distance running legends including World Record Holders in the mile in 1994 and there was also an expanded group of champions who gathered in 2019. How meaningful is it to meet with these groups of athletes and their families who have been the world’s best and can share their common thoughts on racing to the top in the good old days?

|

| FB |

That is great when they bring the mile and 1,500-meter World Record Holders together. In 2019 it was organized by the Monaco National Museum. Those three days staying in Monaco with our families was great. I went with my late wife. People appreciate each other. The different international federations were appreciative. Bringing us all to Monaco with dinners and other functions was very good.

|

|

| GCR: |

Your autobiography, with the appropriate title, ‘Catch Me if You Can,’ written with Myles Schrag, was published in 2022 and I truly enjoyed learning details of your running and your life. How can people order your book and are there autographed copies available?

|

| FB |

If someone wants an autographed book, they aren’t available. The book is sold in major bookstores in the world and online through Amazon and other websites. People can just go on their computer on Google and find the links.

|

|

| GCR: |

One of my favorite items in ‘Catch Me if You Can’ are photos of your late wife, Anna, and you. Several aren’t facing the camera but are of the two of you facing each other with warm smiles and love in your eyes. How important was Anna, who passed away a bit over three years ago, in your life’s journey?

|

| FB |

That is very difficult for me because my wife was a hard worker and was my mentor. All the years when I was running abroad, she was the one taking care of the kids. Even when I went to America to school for six years, she came to America for some visits, but she was the one taking care of the kids and taking care of our small businesses. We had poultry and saloons. When I was running, I didn’t make much money because of amateurism, so she was taking care of many finances. The kids were usually born when I was away running, so she was taking care by herself. To be honest, her death really put me off. It was difficult for me to believe it. She was the Director of the schools. I am glad that now my youngest daughter, Elizabeth, is the Director. Elizabeth and my daughter, Harriet, are taking care of the school since I spend most of my time with the National Olympic Committee. I have no time to rest since I do my work with the Olympic Committee and then have to visit my two schools, one in Kabaha and one in Dar-es Salaam. Sometimes I stay in the office working until seven o’clock in the evening.

|

|

| GCR: |

You served as Secretary General of Tanzania’s National Olympic Committee from 2002 to 2012 and again beginning in 2016 and you will serve through the 2024 Paris Olympic Games. What have been your goals and objectives in your leadership role and what is different the second time you have served?

|

| FB |

Right now, I am more experienced but, when you get more experience, it is time to retire. We can only stay so long. I will retire later this year in December, and I will be seventy-one years old. I will still spend time with my schools. They need me to assist them.

|

|

| GCR: |

We talked about the Filbert Bayi Schools earlier. What can you tell us about other work you do with your health care and sports facilities?

|

| FB |

The health center is doing very well. We started with a dispensary and now the health center is helping the community around us plus is helping the students. Within the school, there is the Filbert Bayi Foundation. It is running the health center and sports center. We have hostels and a place to hold conferences. We have many clubs who hold their competitions at the sports center. My school is also the Olympic Center. There are many activities for young children to play games and sports. There are activities for the children like singing, carpentry, and gardening. Most of the activities are funded by the Olympic Foundation, through the IOC, or Olympic Solidarity. The Kibaha Center is very busy with many sports for the children.

|

|

| GCR: |

As busy as you are with the Olympic Committee, your schools and health care and sports facilities, it doesn’t leave much time for healthy habits. What are you doing now for health and fitness?

|

| FB |

I have been broken to pieces. I have had two knee replacements. At the moment, I am having hip joint problems and need an operation. I am dieting with no red meat, no rice, and no starch. I eat fish, chicken, vegetables, and salad. I walk three or four times a week for five kilometers and that’s it.

|

|

| GCR: |

I’m sure you are called upon to give speeches or advice. In your ‘Catch Me if You Can’ book, there were several times when you spoke of three keys to living a legacy – Confidence, Commitment and Sacrifice. Is that what you truly emphasize to kids?

|

| FB |

I always tell kids that, if they don’t commit themselves, they will never pass their exams. I say that they have to work hard. If you don’t work hard, nothing comes free, and you can’t gain anything. You must sacrifice your time. There is leisure time and business time. If you are far behind, your time that was leisure time must be used for business. Leisure time doesn’t pay but, if you work hard and sacrifice your leisure time, you will gain more. But, two plus two cannot be five. It must equal four. What ever you think you can do; you must do it then which is the right time.

|

|

| |

Inside Stuff |

| Hobbies/Interests |

I usually read sports magazines and listen to music on the radio

|

| Nicknames |

My nickname that my mother gave me was ‘Habi.’ Habi is actually ‘Habiyet’ and it means hyena. My mother gave me this name because, when she was carrying me, my father died in a place called Mbulu. This place was 48 miles from where I was later born, so my mother walked during her pregnancy to Mbulu where my father died. At that time, there was no transport. They walked from Karatu to Mbulu. She was accompanied by my uncle. They slept in people’s houses on the way. There were so many hyenas in those days that she could hear outside while she was staying in these houses. When I was born, the first name she gave me was ‘Habiyet.’ It is from one of the tribes in Tanzania called Barabaig. My mother was Barabaig and gave me the nickname which meant hyena

|

| Favorite movies |

Action movies, especially from America

|

| Favorite music |

I like pop music, reggae, and rhumba

|

| Favorite books |

Sometimes I read novels or sports books. I read one about Michael Johnson and like books written by the athletes, even football and basketball

|

| First car |

In America, I had the old model Toyota Celica. I left it to some friends and gave it free

|

| More cars |

When I came back to Tanzania, I bought a Volkswagen Variant. Then a Peugeot 404, Peugeot 504, Peugeot 505, a Landcruiser Prado. Then I had a Mercedes Benz while I had the Landcruiser. I sold the Landcruiser and bought a Toyota Amazon. I still had the Mercedes Benz

|

| Current car |

I sold the Toyota Amazon and bought a Toyota V-8 which I have now

|

| First Job |

When I was in primary school in Karatu, I was selling bananas. One of my friend’s parents had a banana market. After school, I would sell bananas. I got a little money. The currency was very strong back then. They would give me one shilling or two shillings which was a lot of money

|

| Family |

My mother was Magdalena Qwaray, and my father was Bayi Sanka Irafay. As we talked about, my father passed away before I was born, and my mother raised me. My late wife is Anna. I have four kids – two girls and two boys. I have eleven grandchildren. I also have a few great-grandchildren. I like my family to be together and to help each other. We must be respected and respect each other

|

| Pets |

I had a dog called ‘Simba’ which is the one I used to hunt with when I was herding cows in Karatu. That was in the 1960s. I have dogs now in Dar es-salaam. They aren’t hunting dogs but are security dogs

|

| Favorite breakfast |

In the mornings, I have brown bread. Sometimes I have French toast. I eat yogurt, a banana or apple, and a cup of tea

|

| Favorite meal |

I don’t eat dinner but eat a late lunch. I don’t eat dinner because in the evening we don’t go anywhere and the food stays in my stomach. The food eaten in the evening finds a way to form fat because I am inactive. I eat between three o’clock and four o’clock. In the evening, I might have a piece of carrot or cucumber or salad

|

| Favorite beverages |

Water and tea

|

| First running memory |

There was a game at school. Every evening, we would march into the field in our school uniforms and divide into groups. There were those who were playing football, basketball, running or volleyball. We would go to the field. I would go from football to basketball. I would move from place to place because I loved to play each game

|

| Running heroes |

Kipchoge Keino and John Akwhari

|

| Greatest running moments |

Number one definitely would be the 1974 Gold Medal and World Record at the Commonwealth Games in Christchurch. The second is the 1980 Silver Medal in the Moscow Olympics. The third one is the World Record mile in Kingston. The fourth one is in 1973 when I won the African Games 1,500 meters ahead of Kipchoge Keino

|

| MOst disappointing moment |

In 1977 in Oslo at the Bislett Games when I was spiked. That was the first time that I ran in the group of runners, and I was spiked by the Kenyan, Mike Boit. It was only my second race that year in Europe. When I was spiked in my knee, I was told not to race any more for the whole year of 1977. So, I missed the rest of the competitions

|

| Childhood dreams |

I don’t know what I wanted to be because I was doing everything at that time. I didn’t think about being the President of the country. What I wanted to be was the champion of something, though I didn’t know what. I wanted to be like someone like Kipchoge Keino. I could see the planes in the sky and the smoke following behind them because of the cold. I thought it was a snake. People told me it was a plane. I wanted to be on a plane. I said, ‘One day I might board a plane and travel a far distance

|

| Funny memories |

I don’t drink alcohol, so I don’t get that much company. I don’t go out and drink a beer. I’m just a home boy. I’m just a house boy. I stay at home

|

|

|

|

|

|

|