|

|

|

garycohenrunning.com

garycohenrunning.com

be healthy • get more fit • race faster

| |

|

"All in a Day’s Run" is for competitive runners,

fitness enthusiasts and anyone who needs a "spark" to get healthier by increasing exercise and eating more nutritionally.

Click here for more info or to order

This is what the running elite has to say about "All in a Day's Run":

"Gary's experiences and thoughts are very entertaining, all levels of

runners can relate to them."

Brian Sell — 2008 U.S. Olympic Marathoner

"Each of Gary's essays is a short read with great information on training,

racing and nutrition."

Dave McGillivray — Boston Marathon Race Director

|

|

|

|

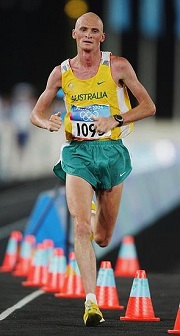

Lee Troop is a three-time Australian Olympian at the marathon distance, in 2000 in Sydney, Australia, in 2004 in Athens, Greece and in 2008 in Beijing, China. He was a member of four Australian World Cross Country Championship teams with a top place of 21st in 2004. Lee finished 18th in the 2001 World Championships Marathon in 2:11:46. He raced his personal best marathon time of 2:09:49 at the 2003 Biwa-ko Mainichi Marathon where he finished seventh. Troop won the 2014 Australian Marathon Championship at the Gold Coast Marathon in 2:14:13. His other top marathon finishes include his debut 11th place at the 1999 London Marathon in 2:11:21, sixth at the 2001 Rotterdam Marathon in 2:10:04, eighth at 2004 London Marathon in 2:09:58 and sixth at the 2007 Berlin Marathon in 2:10:31. At the 1999 Melbourne Track Classic, Lee raced 5,000 meters in 13:14:82 to break Ron Clarke’s Australian Record which had stood for 33 years. At the 2003 Taranaki Twilight 10,000 meters in Inglewood, New Zealand, he set his personal best of 27:51.27. Troop represented Australia at the 1998 Commonwealth Games in the 5,000 and 10,000 meters, finishing sixth and seventh, respectively. He is a seven-time Australian Champion, which are included in his over thirty total professional victories. In 2014 Lee won the New York City Marathon Masters title in 2:25:09. On the roads his top performances at shorter distances include winning the 1997 City to Surf 14k and second place at the 1999 Tokyo Half Marathon in 1:01:00. His personal best times include: 1,500m – 3:50.20; 3,000m – 7:41.78; 2-mile – 8:30.14; 5,000m – 13:14.82; 10,000m - 27:51.27; :15k – 45:21; 10-miles – 47:43; half marathon – 1:01:00 and marathon - 2:09:49. Troop began coaching in 2011 and his most notable accomplishment is Jake Riley’s second place at the 2020 U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials. Lee resides in Boulder, Colorado with his wife, Freyja, and their three children. He was very kind to spend two hours on the telephone in late 2020 for this interview.

|

|

| GCR: |

THE BIG PICTURE As you look back on your running career and a solid twenty plus years of strong training and racing, how exciting was it to be putting in the hard training and racing and pushing yourself to try to reach your ultimate best in terms of times and competition?

|

| LT |

When you are out there participating in sport and then it becomes a job, you are always shooting for the highest point that you can. For me, I got involved in running for my dad. He wanted to lose weight and it went from winning a few local school races to making some teams. Then as I got better and better, there were always goals that I was trying to achieve to keep myself motivated. My ultimate goal was to try to break Rob de Castella’s Australian marathon record which is 2:07:51. Throughout my career of twenty years, that was always the goal that I was focused on and which I wanted to achieve. Unfortunately, I didn’t but there was no better feeling than waking up every day with a pep in my step and a goal to chase that I had every one of those days throughout my career.

|

|

| GCR: |

Few athletes make it to one Olympic Games. When athletes do so, often they hope to make the top ten or a final or to medal. In retrospect, how much of an honor and career achievement was it to compete for Australia in three Olympic Games?

|

| LT |

There is a two -part answer to that question. First, there is no greater honor than representing your country. To have that bestowed upon me is something I will always cherish and never take for granted. On the flipside, the biggest blank I have on my career is my performance in my three Olympic Games. Unfortunately, it never went right. That is an area where I look back on my career with disappointment. People will say to me, ‘You made the Olympics. You should be proud of that.’ But, as elite athletes, we are always striving and are goal-oriented and that is what motivates us. When we earn sponsorships, they are not just because we are good people or nice people, but it’s because we’re great at what we do and companies back us to achieve certain goals. When I ran in the Sydney Olympics in 2000, it was a home Olympics, and I was motivated to run well and try to make the top ten. I was fourth at halfway and then at 23 kilometers I tore a stomach muscle. That was my rectus abdominus and at the time I didn’t know that. It felt like a stitch that was getting progressively worse and worse and worse. I ended up limping to the finish in 66th position. There was a lot of torture and torment and heartache. I struggled to accept that result. Moving forward with my next two Olympics in 2004 and 2008, I went into those Olympics with so much baggage because I wanted to make amends for what happened in Sydney. I was so determined to finish in the top ten and prove to myself that what happened in Sydney was a freakish occasion. Unfortunately, I cooked myself going into the Athens Olympics in 2004. I trained way too hard and, in the race, it was like a car with five gears and only four were working. When I got to Beijing in 2008, I was struck with the same curse of training way too hard. I was so goal oriented and so focused that it ended up being to the detriment of my performance. If you look at my career, I ran well at Rotterdam and Berlin and ran under 2:10 a couple times, at 2:10 a couple times and 2:11 a couple times and those races were great. But the thing to this day at forty-seven years of age that I struggle to come to terms and grips with is my Olympic performances.

|

|

| GCR: |

Sticking with the theme of competing for Australia, how much of a privilege was it to pull on your country’s singlet the more than a dozen times you did so at the World Cross Country Championships, Olympic Games, World Track and Field Championships and other competitions?

|

| LT |

Again, there is no greater honor than representing your country. We are a country of twenty-five million people and I got to be one of those people that was able to represent my family, my friends, my hometown, and my whole country of Australia. When you’re a kid and are running in local races, you have dreams and aspirations about being able to do that one day and I got to do that for twenty years. It is something that I was very privileged to be able to do and something that I loved to do. In Australia we have this tradition that when you go to a major championship, and particularly the Olympic Games, if you pull out or DNF, you must take your singlet off and leave it on the side of the road. As Australians, we have this brethren, this brotherhood of tradition that when you wear it you never take it for granted. You give the best account of yourself that you can and if that means that you limp across the finish line, as long as you finish what you started, you’ve done Australia proud. And if you can’t finish then, unfortunately, the singlet has to come off and it stays on the side of the road.

|

|

| GCR: |

Did you ever have that happen to you? I don’t think I recall where that did.

|

| AA |

No, I did not. I was always motivated by that and did not want to be the first Aussie ever after guys like de Castella and Moneghetti to be that guy. I remember in Beijing in my last Olympic marathon I certainly contemplated that. I hit the wall at seventeen kilometers, so it was a very long and lonely and heartbreaking run into the finish. I certainly considered that, but it didn’t happen.

|

|

| GCR: |

After racing cross country and both the 5,000 and 10,000-meter distances on the track in the late 1990s, you added the marathon to your competitive schedule and focus. What were the primary factors that led to this decision?

|

| LT |

I always wanted to be a marathoner. Unfortunately, I was held back. I would have liked to run the marathon earlier in my running career than I did. In 1999 I broke Ron Clarke’s Australian Record for 5,000 meters that had stood for thirty-three years. Everyone wanted me to stay on the track. The head coach of Athletics Australia wanted me to stay on the track. There was this excitement that we had finally been able to bridge the gap after such a long time. Unbeknownst to everyone, even though I ran track and cross country, I was always destined to be a marathoner. It was something I always wanted to do as I had grown up idolizing Rob de Castella.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned your Olympic results where you trained to hard and it was a detriment to you. From my ow n running, my teammates and friends, and those I have interviewed, competing is often a roller coaster of results due to the tough training that has us treading the fine line between improvement and injury. How tough was it for you to find that balance that led to peaking at the right times for your most important competitions?

|

| LT |

Ironically, in the early part of my career it wasn’t that hard. I hadn’t been injured and certainly hadn’t faced any adversity. I didn’t have any resentment toward anything. It was like Billy Mills and the concept of running free. I got out there and trained hard and raced hard and had camaraderie with all my friends. I got better and better and better and better every year to the point where I broke Clarke’s record in 1999. Then things started to change a bit. In 1999 I made the World Championships which was in Seville, Spain. I was the only athlete that qualified for and was selected in the 5,000 meters, 10,000 meters and the marathon. All I wanted to do was to run the marathon. But our officials and coach were saying that there hadn’t been anyone who had run that fast on the track in thirty-three years, so they basically vetoed my opportunity to run the marathon. That led to a lot of frustration and anger. I was thinking that if they were going to control my destiny, I was going to train harder than ever and prove them all wrong. Having that simple mindset meant that I was no longer training hard and doing it because I wanted to. I was doing so because I felt I had to. Suddenly, I had a little niggle here and injury there and was taking some time off. That frustration and anger magnified itself even more. I’ve been retired for a while now, and when I reflect on my career, I got to a point where I started to accumulate these bricks on my shoulders. It’s hard to run with a clean heart and a clean mind when you do start to accumulate these bricks. For me, that is where that fine line became very fine. There was not much wiggle room between training hard and overtraining. I was so mentally driven that I wasn’t listening to my body. My brain was controlling everything. When you run with a lot of anger and frustration it is amazing how you can push your body to the brink of breaking down which I started to do a fair bit particularly toward the end of my career.

|

|

| GCR: |

When your competitive days wound down, you transitioned to coaching others. With elite athletes you coached, what did you learn from your own training, racing, and running often with anger instead of joy do to help them to move to a higher level of maximizing their improvement and minimizing their injuries?

|

| LT |

The mental component compared to the physical component of running is three to one. My athletes aren’t going to do anything different than what I did. But it is how they implement or move forward that I try to change. People that know my training know it’s not rocket science. It’s basic training. What we’re trying to do is to get the cumulative effect of every day, of every week, of every month and build up over two or three years while staying healthy, staying injury-free and enjoying what they do. I feel that strength that I bring to the table is more the mental and the psychological point when athletes are feeling down, and things are going wrong. I’m picking them up and trying to tweak training around a bit to accommodate what they are going through. So many times during my career, training was etched in stone. It couldn’t change. If I was scheduled to do twelve by 400 meters at the track, I did twelve 400 meters, regardless of how I felt or what the weather was like. Coming into the coaching realm, I’ve certainly tried to be more flexible in that regard. When they are down, I’m building them up. And when they are going very well, I’m trying to hold them back, so they don’t end up going too hard, too fast, too far and then burning out. Particularly through this COVID-19 pandemic its required and I want more navigating from that psychological sense of just being there for athletes. Everyone is dealing with it in a completely different manner. So, I have added more flexibility into my coaching to be sure that mentally they are happy, on top of things and have the full support of their coach moving forward. Again, the greatest asset I bring is making sure the athletes train as hard as I did and are as motivated as I was, but don’t make the same mistakes that I made.

|

|

| GCR: |

Switching gears back to your own racing, you said you were destined to be a marathon runner, but with your great success at on the track at 5,000 meters and 10,000 meters, in cross country and on the roads in the marathon, and shorter distances, what is your favorite racing distance and venue?

|

| LT |

There’s no doubt – cross country. Cross country is the bread and butter of distance racing and I was very fortunate to be part of the very old school of cross country. There were three hundred runners turning out and only one distance of twelve kilometers. There were runners who were milers to marathoners and, when that gun went off, the goal was to be in the top one hundred. If you could finish in the top third of the World Cross Country race, you had done very well. I got to experience my first World Cross Country Championship in South Africa in 1996 and that is something I loved. It wasn’t about splits. It wasn’t so much about rhythm. It was that grind of making sure you could keep throwing everything you could at your competitors at every turn, at every hill and at random points in the middle of the race. Cross country was my major love.

|

|

| GCR: |

RACING Let’s chat first about cross country racing. You won the Australian Cross-Country Championships several times and had a few more times where you made the podium for being in the top three finishers. What are some highlights from these races in terms of beating tough foes to qualify for the World Championships?

|

| LT |

The greatest cross-country runner we had in Australia was Steve Moneghetti. I was very fortunate to train with Steve and to live in the same town he was from which is Balarat. I learned very early on how strong I had to be to race him. He was one of the toughest Australian athletes I ever raced against and he loved cross country. He could turn it on like there was no tomorrow. I had to rise to the occasion, and I took a lot of satisfaction when I beat Steve because I knew he was the one athlete that would always have me on the ropes. He would always be the guy that would make it extremely difficult for me. He had an impeccable international career and an impeccable cross-country career. He was fourth at World Cross Country. He was my greatest rival, but I say that in a friendly way. He always brought out the best in me.

|

|

| GCR: |

You raced multiple times in the World Cross Country Championships from 1996 to 2004 and improved your placings from 66th to 60th to 41st to 25th and 21st place whether you were focused on track racing or the marathon. What was it like to be racing against the best in the world from the mile to the marathon who all came together and what are some of your takeaways from your race plans, tactics and the competitions that stand out in your mind?

|

| LT |

The first one was in South Africa where I was 66th. To finish in the top one hundred when there were three hundred competitors for my debut was a great performance and I was very happy. The second one in 1998 was in Marrakesh and I struggled with the heat. It was an extremely hot day. I’m a red head and red heads aren’t known for running well in the heat. So, I sort of struggled. The third time was in Belfast and I was sick. That was another rough day for me. The next one was in Oostead in 2001 and I was having the race of my life. I was running with Bob Kennedy in the main pack. Around 4k I slipped. It was on a racetrack and was very muddy. I went down and, by the time I got up, I was back in about 35th position. World Cross Country is so competitive with the number of athletes that you can’t give up one or two seconds, let alone slipping. I worked myself up to about sixteenth or seventeenth place. Then in the last mile I ran out of gas and got run over the top. My last race in Brussels it was a tough one. It was a 2k loop and we ran six laps. Everyone obviously flew out at the start. Being a marathon runner, I was not that fast. I had to work hard in the middle stages of the race to get myself in and around and out into 21st place. I had a great battle with John Brown. The thing I found the hardest about World Cross Country is I always did that as my final race leading into a marathon. For example, the London Marathon would be three weeks afterward. Having to travel 24 hours from Australia to where we raced was tough. Particularly that year we were in Marrakesh as we flew from Australia to Hong Kong, from Hong Kong to England, then to somewhere in South Africa and then we flew to somewhere else where we were stuck in an airport hanger for about six hours. Then we finally flew out to Marrakesh. I always found those races served their purpose for me regarding the marathons that I had coming up three or four weeks later.

|

|

| GCR: |

Switching focus to the track, in 1998 at the Australian Commonwealth Selection Trials you won the 10,000 meters and were third in the 5,000 meters. How exciting was it to qualify to represent Australia in two events at the Commonwealth Games?

|

| LT |

I was extremely proud of my performance there. It was the first major Australian team for me.

|

|

| GCR: |

You finished in seventh place in the 10,000 meters and sixth place in the 5,000 meters at the 1998 Commonwealth Games. What were your race strategies, how did the races play out and was it all you could do to place as high as you did?

|

| LT |

In the 10,000 meters I ended up getting beaten by Steve Moneghetti. I’ve talked about how competitive we were. We trained hard for that and he ended up getting a Bronze Medal. I was the only athlete who came back and did both races. I did the 10k final, had a day’s rest and came back in the 5k heats. Then I did the 5k final and ended up third in my heat and sixth in the final. The fact that I got 20k of racing done in four days highlighted to me that I was going to be a marathoner.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned briefly running your personal best for 5,000 meters of 13:14:82 which broke Ron Clarke’s thirty-three-year-old record. This was done at the 1999 Melbourne Track Classic for 2nd place. Who were your primary opponents in that race and what were the key points that led you to racing so much faster than you did the previous year?

|

| LT |

Just to go back a little bit, we talked about my running in 1996 in South Africa, in 1997 great cross country running and then in 1998 World Cross Country and the Commonwealth Games. Everything was getting better and better. I was getting faster. I was getting stronger. I had a lot of joy. Running and training hard was such a blessing. The cumulative effect of every week, of every month, of every year was starting to pay huge dividends for me. So, in 1999 I was excited because I was going to be debuting at the London Marathon. I started out the year in Tokyo, Japan and I ran a half marathon in sixty-one flat and finished second. It was a very slow race in the beginning. The first 10k was 29:22. My next 10k was 28:34 and I finished off my last 5k in 14:09. I still got second. When I came back from there, I knew that I had the London Marathon approaching and I was going to do some track races as part of my training. I did 3,000 meters where I finished third in 7:41.7. I remember in the race there was a guy, Lucas Kipkosgei, who was number two in the world at the time and another runner, Ben Maiyo, who was number four in the world. We went through the first 1,500 meters in 3:50.3 and my PR was only 3:46. With 700 meters to go I went to the lead. Lucas and Ben came flying around me and, when I finished in 7:41.7, I remember Moneghetti and others running across the track saying I’d broken the Australian Record. I didn’t even know what the Australian Record was. I said, ‘No, no, you got to be kidding me.’ Anyway, I missed it by zero point one seconds. I was thinking that I had done 3:50.3 and 3:51.4 back-to-back and the 5k was in five days’ time. I was only doing these races as part of my training going into London. Everyone started talking about how I could break Ron Clarke’s 5k record. My goal was to run 13:20 to 13:30. I didn’t have the record as a major goal. Anyway, we jumped into the race and Graham Hood, the Canadian miler, was the one who did the pacing. We took off and went through 3k in 7:57. I had gone to the lead a couple times. Then I tried to do the same thing with 700 meters to go to see if I could squeeze a bit out of Lucas Kipkosgei. I couldn’t and he ended up running 13:11, I was 13:14 and Ben Maiyo was about 13:21. I crossed the line and broke Clarky’s record and I was stunned more than anyone. I was preparing for London. Ron Clarke was such a tremendous athlete. There had been thirty-three years of great Australian athletes that didn’t break it and here I am just as part of my preparation for London getting out there and breaking it. I think that also added to why I was so relaxed. I wasn’t thinking about the record. I just wanted to race Lucas as hard as I could, and I wanted to turn the tables on the 3k from five days earlier. I went in there just thinking, ‘I should run aggressively. It doesn’t matter. He’s number two in the world. This is Melbourne – in my home state.’ I went out there racing to win and ended up getting the record as a bonus for that.

|

|

| GCR: |

As you mentioned, shortly after you set your 5,000-meter personal best and raced strong at the World Cross Country Championships you ran the 1999 London Marathon in 2:11:21 which was good for 11th place. How was that race in terms of running so much slower than your track races, instead of 4:15 mile pace for 5k running five-minute mile pace for over two hours? And how was the change from thirteen minutes of intensity to two plus hours of keeping under control?

|

| LT |

It wasn’t that hard because, as I mentioned, I had run the Tokyo half marathon in January in sixty-one flat off a slow early pace. So, I had the strength from the half marathon, and I had the speed from the 5k. I did go to World Cross Country in Belfast and was sick, so I didn’t have a great World Cross Country race. But I had faith in the training I had done. London was my debut and I remember going with the lead pack. El Mouaziz took off at the start. I was in a pack with Antonio Pinto and Renaldo de Costa, the World Record Holder at the time. I was looking around and almost pinched myself. My dream had become a reality. I remember leading the pack over the tower bridge. It lived up to the hype of what I had spent my whole life dreaming about. We got to about 34 kilometers, so there was about five miles to go. Pinto through in a surge which I couldn’t respond to. John Brown was there who had been to two Olympics. I was trying to hold onto that group for as long as I could. I ended up running 2:11:21 on debut and, at that time, the only other Australian who had run faster on debut was Steve Moneghetti who had run 2:11:19. Mona and I are great friends, great training partners and have a lot of PRs that are very similar. That was another one that was extremely close. I crossed that line and all the hurt and the pain that I had started to experience over the last couple miles was worth it. It was awesome to finally be part of the marathon club.

|

|

| GCR: |

Then, as we mentioned, your marathon racing was like a roller coaster with a low in the 2000 Olympics before you rebounded the next year at the 2001 Rotterdam Marathon with a personal best of 2:10:04 for 6th place. Did you run even pace, who did you race with in the pack and what was it like as you approached the finish to try to dip under 2:10 and come so close?

|

| LT |

It was a strange race because I came off the disappointment of Sydney and tearing a stomach muscle, which we didn’t know at the time that I had torn my rectus abdominus. My thoughts were to get back on the horse again. I prepped for Rotterdam and went out with the second pack in the race. The second pack went through halfway in sixty-four minutes to sixty-four ten. The whole pack slowly whittled down, and I was sort of stuck in no man’s land for probably at least a good ten miles towards the end. I didn’t realize I was so close to breaking 2:10. But, when I ran 2:10:04 and finished sixth, it made amends for the disappointment of Sydney.

|

|

| GCR: |

After coming off such a great race at Rotterdam, what was your action plan for the remainder of 2001?

|

|

|

Unfortunately, I again got to the point where suddenly things changed, and my mental psyche was to start training harder. The 2001 World Championships were in Edmonton and I didn’t want to run that race at slight elevation and grind away when I knew there wouldn’t be a lot of top athletes going there. So, I was decided to run the Chicago Marathon. Three weeks before Chicago I tore my calf and, unfortunately, I had to withdraw.

|

|

| GCR: |

That elusive sub-2:10 came for you two years later in 2003 at the Biwa-ko Mainichi Marathon in Otsu, Japan when you improved your PR by fifteen seconds to 2:09:49 with a 7th place finish. What were highlights of that race, when did you know you were going to break 2:10 and how was it racing in Japan with their culture that looks so favorably on marathon runners?

|

| LT |

It’s amazing. Nothing compares. Japan is definitely the home for marathon running. When I went to Biwa, I had run 2:10 in 2001 and was injured for much of 2002 but things started to click for me, and I started to get some consistency in 2003. Two weeks before I ran Biwa, I ran 27:51 for 10k in Inglewood, New Zealand, so I knew I was in great shape. I had done a lot of the work in that 10k and I took the win. So, going into Biwa I knew I had a good shot at running 2:08 or 2:09 and that was certainly the goal. Steve Moneghetti was a pacemaker for us, and we went through the half marathon in sixty-three fifty and the first 30k at just over ninety minutes. I was feeling amazing. I was clicking the back of his heels. We were at 30k when Steve pulled off to the side of the road. He said, ‘Keep going. You’re running well.’ There was a pack of five or six of us. I turned around and said, ‘Deke’s record is going down.’ We got through about thirty-four or thirty-five kilometers and it felt like I got hit by a truck. I started getting tired and started going backwards and suddenly that sub-2:08 started to slowly disappear. Then that sub-2:09 slowly started to disappear. I came onto the track and my quads were screaming. I saw the clock and knew that I had to be under 2:10 and I ended up running that 2:09:49 and finally breaking 2:10. That was fantastic, but I left there wanting more. I knew I could run 2:08. It was right there in front of me. That certainly gave me confidence and much more desire to get back home, to get back into training and to keep chasing that elusive 2:07:51 that Deke had set as our National Record.

|

|

| GCR: |

You briefly mentioned setting your personal best 10,000 meters which was 27:51.27 at the 2003 Taranaki Twilight Meet in Inglewood, New Zealand. Did you train at all for 10k or did you race off the strength you had gained from three years of marathon training?

|

| LT |

I’m a strength runner. I’m not a speed or fluid track runner. I specifically picked that race as my lead into the marathon.

|

|

| GCR: |

Later that year at the 2003 World Championships Marathon in Paris, France you had possibly your best race at a global championship, finishing 18th in 2:11:46. After the top six finished in 2:08 and 2:09, you were part of a group of a dozen runners who ran 2:10 or 2:11. Could you take us through the race, how you felt and important points that made the difference between top ten and a top twenty finish when there were so many great runners bunched so close together?

|

| LT |

That race in Paris is a funny story. I flew over to our team camp in Rome. I got off the plane and stubbed my toe. I ran into a steel suitcase or briefcase. My toe blew up. I got to the team camp and our physical therapist was my roommate back in Australia. He looked at it and they bandaged it up. I was able to run on it, as it was a little painful, but it wasn’t sore. Each day it started to get worse and the swelling was worse. They decided I should fly into Paris early to get an x-ray and to see what was wrong with my foot. I flew with the team doctor and my therapist into Paris, went in there and they did the x-rays. The team doctor came out and the therapist came out and they said that basically I had bruised the toe and there was nothing to worry about. They said if they taped it adequately, I would be fine. So, I didn’t think any more about it. I ran on it and when I jumped in the race it hurt a lot when I ran up the Champs-Elysees and down the Champs-Elysees because the road is a cobblestone road. Every time I hit an awkward part of a rock; it was like a shooting pain into my toe. I kept trying to shake it off and was thinking, ‘It’s just a bruise.’ The race played out fairly well. I remember the Moroccans knocking drinks off some of the elite athletes’ tables. I had words with one of the athletes about that. I was there until about thirty or thirty-five kilometers. Julio Rey threw in a surge and that broke up the group. I was running very well up until about thirty-six or thirty-seven kilometers. I started to get tired and fell from about twelfth to eighteenth place. When they took off, and I remember it vividly, there was a slight incline, and I tried to go. I thought it was too much of an aggressive move and I would hold back a bit. But, in that split second where I thought I would hold back, everyone went and, suddenly, the whole pack started to break up. There were just pieces and guys were falling off right and left. I was grinding to try to get past as many people as I could. Unfortunately, I got to that last three or four kilometers and had a few guys come over the top of me. I was happy. It was a top twenty finish, though I would have liked to finish much higher and felt like I could have finished much higher. Of all the World Championship marathons, that was by far the most competitive and the deepest field that had been assembled.

|

|

| GCR: |

How badly do you think your toe injury affected your performance?

|

| LT |

When I finished the race, the guy I roomed with came out on the track yelling, ‘You’re a freak! You’re a freak!’ I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ He responded, ‘You’ve got a broken toe.’ ‘What?’ ‘You’ve got a broken toe.’ In a split second I was super angry because he hadn’t told me. ‘What do you mean I’ve got a broken toe?’ He said, ‘Whether it was a bruise or break was not relevant. If we taped it up, you could still run. We just figured that you being you, if we told you it was a bruise you would be thinking you could push through it. If we told you it was a broken toe, you would contemplate not running and, if it was very sore, just taking the option of pulling out because you had a broken toe.’ That became one of the folklore stories on the Australian team that I was able to run a 2:11 marathon with a broken toe. I thought that was very cool and it reiterated to me how much of our mental capacity we needed to discover. Now, when I coach my athletes, if I can take away one of those fears and thoughts and ideas and just get them to run, then the athlete is going to run a lot freer and a lot cleaner and purer. If an athlete gets more information than is needed to know and starts to get these seeds of doubt, then sometimes that feeds into the mental psyche that can affect overall performance. That race certainly proved that thought. Had I known I had a broken toe I probably wouldn’t have run as well. The fact that I didn’t know had me thinking, ‘Come on Lee. It's just a bruise. Harden up. Just finish off the race.’ It reiterated that from a mental capacity sometimes the less we know the better we will perform.

|

|

| GCR: |

After the 2004 Olympics, what happened that pushed you into your familiar pattern that resulted in injuries which affected 2005 and the early part of 2006?

|

| LT |

Before the Athens Olympics I had pictures on my wall with the Pathenades stadium and had a countdown the entire year before with 365, 364 days to go and so on. Unfortunately, I got to Athens and bonked out again. There were no excuses. I just ran poorly. After Athens I was thinking about how I had two Olympics with bad performances. I came back from that and I was doing a hundred and fifty miles a week. My easiest day was ten miles in the morning and ten miles at night. I was so determined to run well and trained harder than ever. I was training way too hard. I ran for over a thousand days without a day off. I think it was a thousand and eighteen days. Then I happened to be out doing an easy run and I rolled my ankle. I didn’t think anything about it until a couple days later when I was going to do a workout and I tore my calf muscle because of my ankle. The cumulative effect of doing all those 150-mile weeks was starting to show. There were some cracks that were starting to happen. 2005 was a rough year for me. The Commonwealth Games in 2006 were going to be in Melbourne and I really wanted to run. It’s in my home state and I had been our number one marathoner for several years. But I couldn’t get healthy. I went to Fukuoka and had a stress fracture in my back. I ran two and a half hours. I shouldn’t have gone but I decided to not leave any stone unturned. I didn’t want to miss making the Commonwealth Games team by not being good enough on time as opposed to conceding and not going because I was injured. So, I stupidly ran there in two and a half hours and missed the Commonwealth Games. I had to rest. I ended up finding a good practitioner and stated to develop a good support crew around me. My wife and I were expecting our first child. So, a lot of things were coming into play that were a calming influence for me. The best thing to describe me is being a sprinter in a distance guy’s body. Sprinters are all bouncy and edgy while distance guys are more mellow and placid, but I certainly wasn’t like that. I started to get my body healthy and identify several old injuries that were creeping in to change my biomechanics. I started doing Pilates and other strengthening exercises.

|

|

| GCR: |

What was your action plan that resulted in you winning the 2006 Gold Coast Marathon in 2:14:13 by over three minutes, running splits of 1:05:08 and 1:09:03? How cool was it to win the Australian Marathon Championship after coming back from injury and did you savor the crowds in the final few miles when victory was at hand?

|

| LT |

I decided in 2006 that I would go back to basics and spend the first half of the year getting fit and getting healthy. I aimed for the Australian Marathon Championships in July, the Australian Cross-Country Championships and then I would finish off the year with the Australian 10,000-meter Championships. I also figured it would be humbling for me to get back to running National races. If I couldn’t do well at National races, how could I have the grandioso dreams of being an international athlete? I went to Gold Coast and set up pacemakers to run 2:10. The first pacemaker dropped out at 10k and I was left just Mona and me. We had taken off from the start. Mona got me to halfway in just under 65 minutes and, basically, I was on my own from there. I ran 2:14 on a relatively warm day pretty much on my own. I remember basking in the glory of that last half mile and high fiving the crowd. When I got to cross the finish line, my wife and my four-month-old baby were there. It was a cool situation to be in. It gave me the motivation and satisfaction inn knowing I made the right choice. I got myself healthy and this was all about the bigger picture of trying to make my third Olympic team in 2008. A couple months later I ran the Australian Cross-Country Championships, which I won. Then I ran the Zatopek 10,000-meter Championships, which I won. To win three Australian titles in a span of five months certainly got me back on track and excited about moving forward.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned that you trained too hard for both the 2004 Athens Olympics and 2008 Beijing Olympics. Do you think that race temperatures, which were in the mid-eighties both times, also contributed to your results? If it was a cool day in the fifties, could the overtraining have affected you less or were you just too beat up no matter the weather?

|

| LT |

I can say with all honesty that, even if the weather had changed, I might have moved up a few places, but I suffered from the Olympic curse. I didn’t look at it as another race. For me, it was much more, and it all goes back to what happened at the Sydney Olympics. I was so close in Sydney. I was fourth at hallway and believed I could be in the top ten. To be that close and then to miss it, I went into the next two Olympics with too much passion and vigor and determination. I wasn’t listening to my body. I probably should have been getting more rest. There were times where I should have tweaked a few workouts because I was so flat and tired. It would have been good to have an easy week to get me to physically bounce back. But mentally I was so driven that I wasn’t reading any of the signs of my body. I would wake up tired and go to bed super tired. I did that every day and that was the life of a distance runner. Again, hindsight is great twenty-twenty. When I look back, I didn’t have what I needed and that was someone to pull the reigns and tell me what to do. To be fair, the reason I didn’t have that is I probably wouldn’t have listened anyway because I coached myself. Stubbornness and immaturity on my behalf led to overtraining. Everything else I got right. I got my cross-country races right and my track races right and city races right. I could control the environment and they were just races leading toward something bigger. But that bigger thing was the Olympics and that was only thing where I wanted redemption. I can tell you here and now, if I had just got one top ten, the contentment would be there and the beating myself up would be nonexistent. That is the price that comes with being an elite athlete. We are so driven that we end up turning ourselves inside out with what we put ourselves through. It’s taken a fair bit of time to be able to look at things in a holistic sense and an analytical sense and to say this this is what I did wrong. Now that I am a coach, I can’t allow these things to creep in with my athletes.

|

|

| GCR: |

Shortly after the 2008 Beijing Olympics, you moved to the United States with your growing family as you were in your mid-thirties and in the latter part of your running career. The next spring you raced the 2009 Boston Marathon in a respectable 2:16:21 for 13th place. What are highlights from racing in this iconic race on such a historic course?

|

| LT |

The Boston Marathon changed everything for me. For Beijing I had qualified with a 2:10 at the Berlin Marathon where I finished in eighth place and qualified for my third Olympics. Then, unbeknownst to me at the time, I fell back into the same terrible path and didn’t run well at Beijing. The tough thing about being in a small country like Australia with twenty-five million people is that you are accessible. The tall poppy syndrome exists. I regretted getting off the plane in Australia after Beijing because I had to deal with the critics and the world can be cruel. I said to my wife, ‘Why don’t we go to America for a year? I’ve never done the Boston marathon. I’ve never done the New York City Marathon.’ I always had this thing in my head that New York would be my final marathon. I figured we would come for a year and I’d get Steve Jones to coach me. I didn’t do much after Beijing. I was in a slump and feeling miserable because I had conceded that this would be my last year. I got over here to the States and got into some training and got myself into half decent shape. I certainly didn’t train with vigor that this was going to be an amazing marathon. I just wanted to see this out. But I got to Boston and it rekindled my love. So many years earlier my dad got in shape by running and we followed Rob de Castella and we know the role that winning Boston played for Deke. We know the hundreds of thousands of people who have run the course. Here I am in Hopkinton and running to Boylston Street in Boston, following the footsteps of thousands of runners prior to me. I experienced the crowd and the history. A lot of races have changed because of urban growth and they must change courses and they must fit in with numbers. But Boston has stayed true. It goes from Hopkinton to Boston and hasn’t changed. It’s an iconic event. I remember finishing in thirteenth after a big battle with Brian Sell. It rekindled what marathon running was for me. I stupidly said to my wife, ‘Why don’t I try and make a fourth Olympics.’ I was on a euphoric buzz and it shouldn’t have happened, but that’s what I decided. I was going to try and make the 2012 Olympic Games. I couldn’t let it go. I was held back by this redemption. That’s what my goal was but, unfortunately, I ended up having a couple blood clots on my lung and we then had twin boys and then life got in the way for me. I unexpectedly started coaching and I didn’t make the 2012 Olympic Games. Then I decided I would be a master’s runner. I went to Boston in 2013 and won the master’s race. I was thirteenth and thought, ‘Great! I can do master’s running for a few years.!’ But that was the year of the Boston bombing and that derailed everything for me again and I found it hard to get back on top of things. I figured in 2013 I was going to retire, but it wasn’t until the end of 2014 that actually happened. I wanted to run the New York City Marathon to get it over and done with because that was a marathon that I wanted for my last marathon. I e-mailed Dave Monti, but Hurricane Sandy had come through and they weren’t having any international elite athletes, just a handful of American athletes. So, I conceded that the opportunity to run the New York City Marathon was not going to happen. By that time, I was washed up. But a few months later I was at the U.S. Indoor Track and Field Championships in Albuquerque and had a tap on my shoulder. It was Dave Monti and he asked if I was still keen to do my last marathon in New York. I ended up getting that opportunity and closing the chapter at the New York City Marathon in 2014.

|

|

| GCR: |

Speaking of that, you capped off your marathon racing at the 2014 New York City Marathon, winning the master’s title in 2:25:09. Was it fulfilling to still be racing strong past age forty and to be Masters champion and how were the crowds as you raced through the five boroughs of New York City with the crowds, many ethnic groups, signs, and cheering?

|

| LT |

Honestly, I have another funny story. I decided when I was going to run in New York that I was going to train as if I was an elite athlete. I was not going to rest on my laurels and go through the motions. I wanted to make a good account of myself. And I got myself into unbelievable shape. I did the Rock ’n Roll Denver 10k and didn’t realize how hilly it was. One of the things I had to deal with in the latter part of my career was my SIJ, and anyone who has had sacroiliac joint issues knows the nerves and the hips and the hamstrings can be quite troublesome. Anyway, I did the 10k and ran unbelievably well. But, a couple days later I started getting SIJ issues. It got sore and I couldn’t do much training that last two weeks leading into New York. We got to New York and a massive storm had ripped through. The entire start area had been wiped out. I went with the lead pack and we went over the bridge into a howling wind. It was like we were jogging. We were going hard, but the wind was so strong. I knew that I might be in a bit of trouble in that race, so I put a couple ibuprophen tablets in my pocket. After the bridge when we went down, suddenly, the race broke up. I found myself in the second pack. One minute we would run a 2:50 kilometer and then we would run a 3:10 kilometer. Then 2:55 and 3:08. It was based on the wind. At 15k my hip gave out and I was in a fair amount of pain. I said to myself at 15k, ‘Just finish the race. Don’t stop and give up. This is your last race. Finish it off.’ And so, I took the ibuprophen tablets and started going through the motions. I had a lot of people passing me. Friends who were tracking me saw that I was on 2:17 or 2:18 pace but had started blowing up to around three hours. I was getting slower and slower. When I went up First Avenue, the roar was electric. I was hearing, ‘Go Aussie! Go Aus!’ I thought there must be several Australians that had come out to wish me well. I stupidly started waving to them saying, ‘Thank you. Thank you.’ And it was cold and miserable. I thought this was amazing and would probably be the highlight of my run. I got halfway up First Avenue and looked to my left. A guy had no singlet on and on his chest he had painted ‘Aus.’ That’s who they were cheering on. Apparently, this guy was from New York and was well known. I looked across and thought, ‘Oh no. I’m not going out like this.’ I put in a surge. Then he caught and passed me. I thought, ‘No, no, no. Not today.’ I got back in front of him and then he caught me again. When we get to the top of First Avenue, we have to go over a little bridge. I saw a couple of guys at the top of the bridge and sprinted as hard as I could. I got up over the bridge I caught a couple guys and saw someone else out front. So, I took off and, honestly, I ran as hard as I could for the remainder of the race. What was cool, which I didn’t know at the time because I was running with such anger, is that I ended up passing every single person that had passed me. I even passed others and ended up running 2:25. I didn’t feel my hip at all. The ibuprophen must have kicked in and I was running on adrenaline. I didn’t want to get beat by this guy that had ‘Aus’ painted on his chest. I crossed the finish line and I saw the skyline of New York. I blew it a kiss. As I turned around to walk, I crumbled. My hip gave way on me and I and to get myself a wheelchair. If you had to paint a picture of me and everything I’ve gone through and everything I’ve given of myself, New York summed it up perfectly. The odds were against me. I was having a rough day. Somehow, I found grit and determination to think outside the pain I was in and run as hard as I could. I’m still impressed by that performance because I certainly didn’t deserve to run 2:25 and come home as well as what I did. I’ll be forever grateful to Dave Monti for giving me that opportunity to finish my career there.

|

|

| GCR: |

From your many years of racing and training in cross country, on the track and on the roads, who were some of your favorite competitors, in addition to the afore-mentioned Steve Moneghetti, due to their ability to give you a strong race and bring out your best?

|

| LT |

I loved racing Bob Kennedy. He was a great guy. He looked after me in 1999 when I was in Europe for the first time during the European Diamond League. I loved him and had much respect for him. Henrick Ramaala, the South African, is another athlete that always ran hard. I remember racing him at Swansea over in Wales and there was a car on the line for the winner. We were both going and hammering, and he ended up coming away with the new car. He had to sell it anyway because he couldn’t take it back to South Africa. Steve Moneghetti was obviously there. I raced a young Craig Montram, and he was unbelievably good. Mark Davis was another. There were a lot of guys. When you’re at that top level, everyone is out there giving the best account of themselves. The list is longer of the guys I loved racing against that brought out the best in me. There are too many to mention. The thing I also loved is that I would always be having a beer with them after the race. There was a camaraderie which spoke volumes and I don’t see a lot of that today. It’s a bit of a different beast.

|

|

| GCR: |

EARLY DAYS IN RUNNING AND TRAINING Everyone starts somewhere on their running journey. Could you tell us about your beginnings as a runner with your father and then your early days with the Chilwell Athletic Club and how you transitioned from starting out running for fun to noticing you had some talent, and it was time to start competing?

|

| LT |

The short story of a long story is my dad wanted to lose weight, so I ran with him. I played other sports. I did Australian rules football and cricket and karate and basketball. I was multi-dimensional in other sports but running was the sport I loved the most. My dad was an Army man so he would never let me go and do any fun runs unless I adequately trained for them. I started off running with him around the local neighborhoods. We had a thing in Australia called the ‘Life Be In It’ Program and it was all about getting people up off the couch and getting them active. So, in elementary school we would have this competition where for every kilometer you ran you would get a certificate. It was something to color in. I would run before school and I had people counting my laps at lunchtime and I would run after school. I ran through elementary school just for fun. I started off high school and was the fastest guy in my year level but wasn’t the fastest in my hometown. The following year I was the fastest runner in my school, then I was the fastest in my hometown. Then we had to go to the next round, and I wasn’t successful. But fast forward to the end of year twelve and I had won every division. I won my school, local meets, our state meet and the Australian schoolboy championship.

|

|

| GCR: |

Didn’t you make quite an unforeseen turn at that time which landed you in the United States?

|

| LT |

Shortly after that I got an opportunity to go to a junior college in Levelland, Texas – South Plains College. I knew nothing about it. I figured it was like Beverly Hills 90210. I took my surfboard with me because I lived on the beach in Australia. Little did I know that the closest ocean was eight hours away. There was this whole naivete and I didn’t realize I could be a good runner until I ended up at this junior college. I had a great coach and he instilled in me this belief that I could be good. The NAIA and National Junior College levels had the most competitive African athletes because they were in the United States to get good grades and SAT scores to hopefully get into a Division I college. Every week we raced some of the best Kenyan athletes – guys like James Mungali and Julius Rotich. Philemon Hennigan had gone to South Plains just prior to me. Joseph Kengali was there. These were all great runners back in the early 1990s. I had to improve, or I was going to be getting smashed every week. As I said, my coach brought out this belief in me that I could be good. I was there a year and a half, and I went from being okay to being super competitive. I honorably got the nickname, ‘The White Kenyan.’ Then I went back to Australia for Christmas of 1995 with hopes of racing our domestic season to maybe make the Atlanta Olympics. On Christmas Eve I unfortunately was assaulted. I woke up the next morning with a broken jaw and a shattered cheekbone and a blood clot on the brain. So that derailed any chance of at least trying to make the Olympics in 1996. It certainly created a catalyst for everything which happened beyond that and led to the events and races we have talked about from Commonwealth Games to Clarky’s record to the marathon and the career that I had.

|

|

| GCR: |

I’d like to expand on a few of your thoughts. In high school, when you won your state championship and went on to the Australian Championships, what distances were you racing, was it both cross country and on the track and what times were you running?

|

| LT |

I wouldn’t be able to tell you, but I think it was 5k or 6k cross country. Back then, I can’t remember. We have an old saying in Australia that we’re not running for sheep stations and I wasn’t. I just ran because I loved it. There was the thrill of getting out and running and trying to beat whoever showed up. I think it was 5k, not any less and I doubt it was any more. In track I went into the under-20 Australian Championships with a time of 14:18 for 5k. I think I was a minute faster than anyone else. The guy that won is a guy named Andrew Weatherbee that also lives here in Colorado. He reminds me all the time. He is the one who checked the start list and saw that I was a minute faster than everyone else. He wasn’t expecting to do well, but he came away with the win.

|

|

| GCR: |

When you came to the United States and ran for South Plains College, who was your coach and what did he do to change and step up your training from what may have been more loose in Australia?

|

| LT |

The biggest thing is that we were isolated in the panhandle of Texas. We were isolated from bars and clubs. It was a very small town in Levelland. It was tough for a guy like me coming from Australia where I lived on the beach and could drink at age eighteen. Suddenly, I was in a town where there was nothing. I had to make new friends. I had to earn my stripes on the team. The training that we did was different. We would get up at six in the morning and hammer out five miles and then do our workout in the afternoon. It wasn’t necessarily the training. It was the belief of Coach James Morris and his quiet confidence in me. Coach Morris is the one who told me that mental is to physical three to one. He instilled something in me while I was here in this foreign country. Even that was weird because when I had the opportunity to go it was my mom that said I should go. She knew there was no guarantee I was going to be a good runner but if I went for a year or two it would be an unbelievable experience to have with me for the rest of my life. No one gets those opportunities. I didn’t want to go. I had broken up with a girlfriend. My mom told me they would give me a one-way ticket and when it was time for me to come home, they would just pay for me to come home. I figured I had nothing to lose and flew over. It was a long flight from Melbourne to Sydney, Los Angeles, Denver, Dallas and Lubbock and I got in about two o’clock in the morning. I had my surfboard, it was dark, and I couldn’t see anything. I got up at six o’clock and all I could see were cotton fields and oil pump jacks as far as the eye could see. There was a terrible odor I could smell from the oil. Two days in I was thinking there was no way I could handle this. I called my mom and said, ‘This is not for me. I want to come home.’ My mom turned around and said, ‘We knew you’d say that. You’re there for six months.’ And she hung up. I was in a spot where I had to make this work. I was fortunate to have a coach that instilled in me the mental side that I could be a good runner.

|

|

| GCR: |

I wasn’t aware of the assault you sustained at the end of 1995 and am glad you were able to recover. When you could resume training and were able to move to the next level of performances that took you to the Commonwealth Games in 1998, was someone coaching you and what were you doing in training based on your experiences in Australia and Texas? Were there refinements in your training?

|

| LT |

When I came home, I knew that I wanted to be a runner. I lived in a town called Geelong and Steve Moneghetti, who at that time had been to two Olympic Games, lived in a town called Balarat, which was an hour away. So, I surprised my parents when I came home. In half an hour I was in a car and I drove to Balarat and knocked on the door of Steve Moneghetti’s house and said, ‘Hey, I want to train with you, and I want to make the Olympics like you.’ Steve said, ‘If you’d like to train with me, I train at eight in the morning and I train at five at night. I have a three strikes policy. If you want to train with me, this is where I’m going to be.’ So, I just tagged along with him. Whatever training he was doing, I did. I did that for six years. He was coached by two-time Olympian, Chris Wardlow. I went along with the belief that if it was good enough for Mona, it was good enough for me. A lot of the belief in myself came from me. I didn’t have a coach, per se, and the guy I would often seek advice from was also my fiercest competitor. That was the way I would rationalize things and see things and do things. When you’re out there seven days a week, twice a day, every day with a guy who has run 2:08, you just get in, sit down, shut up and hold on. That’s what it was like until I earned my stripes. Then I started beating him and from that things started to snowball.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned running high weekly mileage that reached 150 miles per week. How long were your long runs, how often and at what pace? And what was your weekly training like?

|

| LT |

When I was doing all that training with Mona it was very simple. It was just running two and a half hours on a Sunday. Our training then was ten miles on Monday, Moneghetti fartlek on Tuesday, an hour and forty-five minutes on Wednesday, Deke’s quarters on Thursday, ten miles on Friday and then an eight-mile hill course on Saturday. Additionally, we would run thirty-five to forty-five minutes every evening. That was it. I did that for six years – week in and week out.

|

|

| GCR: |

COACHING What are your key overarching principles that guide your coaching of all athletes, regardless of whether they are elite athletes, 5k and 10k runners stepping up to the marathon, or novices, to help them achieve their goals and potential?

|

| LT |

Everyone is different in what they are trying to achieve. Some people are trying to lose weight. Some are trying to complete their first marathon. Some are trying to make the U.S. Olympic Trials, and some have already made the Olympic team and are getting ready for the Olympic Games. So, it’s important to realize every single person has a goal and we must define what that goal is. That goal then defines what the purpose is. It also defines whether someone is serious or not. By having that defined, it also creates the accountability component of what I need as a coach. If you are accountable to the goal you set, it makes my job easier because all I’m doing then is mapping out the training that is required. As I said before, as a coach these days we play more psychologist. Also, I help with navigating the mental component and minimizing the stresses. The best analogy I can give is it is like a professional rally racing car team. The person driving the car is the athlete. The person sitting in the passenger seat reading the map is the coach. Simply all the person in that seat is doing is telling the driver when to go quick, when there is an upcoming corner and when they need to brake. The rally car driver must have faith in the person who is navigating and giving him that information because, if they don’t, they are going to smash into a tree or go off the road. I take that analogy to the people I work with in that we must have faith in each other. The athlete must have faith in the information I’m giving because I have studied, I’ve researched, and I’ve done it. At the same time, I must have faith in the athlete that he or she will do it. When you create that symbiotic relationship, great things happen. It has been good to see athletes I work with and athletes I no longer work with do well. When there is that poetry in motion, whether it is an athlete completing their first marathon or Jake Riley, who is going to be an Olympian, the euphoria, satisfaction, and sense of success is the same for everyone. We are just at different levels on the pecking order. For each individual, the endorphin release and the emotion we are going to show is the same.

|

|

| GCR: |

How is the marathon training of your top athletes similar and different to your training?

|

| LT |

My training is a bit different here. I have the guys I coach do two hard workouts a week because we are at altitude. They’ll do twenty to thirty minutes on Tuesday and twenty to thirty minutes on Friday. That could be Moneghetti fartlek, Deke’s quarters, or a hill course we have. It could be tight reps. On Sunday they’ll run two to two and a half hours and on Wednesday they’ll run anywhere from eighty minutes to an hour and forty-five minutes. It’s basic. The only time I’ll change their long run segment is when they are leading into a marathon. What I would do, for example with Jake Riley during his buildup, is he will have two long runs of only eighteen miles where the last six-mile segment is at marathon pace. Working back from that, the run gets progressively faster. The first three miles may start at six-minute mile pace and he’ll do that for three miles, then 5:45 pace, then 5:30 and he will slowly kick it down to where his last six miles is done at marathon pace. It sounds easy on paper, but when you’re at 5,400 feet of altitude and you’re doing that off running a hundred twenty or a hundred thirty miles a week, it is an extremely tough workout to do. That is the only time I’ll throw something challenging into the long run. The Sunday long run is about getting out there and getting time on legs. And you’ve got to do that every week for two or three years. That is certainly the staple of the running diet. It is also something that shouldn’t be overcomplicated.

|

|

| GCR: |

I’ve coached individual athletes on the high school level and as adults, both men and women. Could you touch a bit on the coaching you have done of two top women, first Laura Thweatt, in the marathon?

|

| LT |

Coaching Laura was easy. She was from Durango, came to the University of Colorado and didn’t achieve quite what she thought she could achieve. I started working with her and she was a very raw, but very precocious, talent. If I asked her to do something, she did it a hundred times. She always gives the best account of herself. Seeing her progression was amazing. In 2013 she ran the USA 12k championships and she finished third behind Molly Huddle and Shalane Flanagan. That was amazing to her. I remember about two weeks prior to that race we were doing a five-mile tempo run out in the grange. Randomly, without any conversation with her I would take off and surge. Then I would slow down, and she would slowly get up on me. Just when she did, I would take off and surge again. She was getting very frustrated by this. When we finished the workout, she yelled at me, ‘what are you doing? Why can’t you just stick to the pace? Why are you surging?’ I told her, ‘This is racing. Who knows what is going to happen in upcoming races? If someone surges and you aren’t ready for it, you’re going to have to work out how you are going to react to those moves.’ Unbelievably, two weeks later, Molly Huddle takes off and Shalane Flanagan takes off and Laura was having a battle with Kim Conley, who had been an Olympian. Kim threw in this surge and, as Laura was starting to drop off, she remembered what had happened two weeks earlier. She told me she thought, ‘No, no, no. This is what Lee said. I’m going to counteract this.’ She did counteract the move, ended up opening a gap and she finished third. It changed everything moving forward for Laura. She won the U.S. Cross Country Championship here in Boulder. She won three club cross-country championships. She debuted at the New York City marathon and ran 2:28. She went to the London Marathon and did 2:25. She was extremely easy to coach. She embodied the true warrior mentality of training hard and racing hard. Again, using the race car analogy, she obviously did it perfectly well.

|

|

| GCR: |

How different was it coaching Sara Vaughn in the middle distances?

|

| LT |

Sara was a bit of a different scenario because she has just had her third child and she was looking for guidance. She was a 1,500-meter runner and I was fully aware of her pedigree. Working with Sara was different because there was balancing out her family life as well as her running life. The sole goal was to get her to the Olympic Trials in 2016. It was a completely different challenge with her, but it was one that I absolutely loved because she went from having a baby to getting fit to then qualifying for the Olympic Trials. In each round she had a different strategy that she had to implement. She implemented the first strategy fantastically well in her qualifying heat. There was a different strategy in the semifinal race that she implemented, and she made the final. She finished seventh and I was extremely proud of that performance, particularly form where she had come from and what she was aiming to achieve. I don’t think coaching is a case of whether someone is male or female. I think it has to do with where they are mentally. A runner’s mentality derives what a coach will be able to get out of the athlete. They are two good examples of athletes I thoroughly enjoyed working with and I was able to have success with them.

|

|

| GCR: |

Speaking of challenges, we should discuss what turned out to be a pivotal year in 2018. You faced a tragic year with the death of one of your elite athletes, the closure of the franchise running specialty store you operated and then you left your coaching position with the Boulder Track Club. How tough was that period, and what have you learned about yourself that has made you a better coach and person in the past two years?

|

| LT |

They are all different things. The death of Jon Grey is still hard to put into words today. It certainly has changed me because when you are close to someone and you work with someone every day you know the highs and you know the lows. You try to do everything to help. When you don’t expect something like that to happen, it just blows your doors off. Going into coaching today, I have a fear with the athletes I coach. Am I pushing them too hard? Am I not pushing them hard enough? Am I doing enough? How do they feel internally? With the COVID-19 situation, how are they dealing with that? I’m never going to know what was going through Jon’s mind at the time he took his life. It is a frustrating piece because, as a coach, you want to know. It certainly made me more aware. My coaching has always been big groups and ‘rah-rah-rah.’ We’re going to do this or that. This is what I said we’re going to do. Now there is more flexibility to my coaching. There is more understanding. There is more listening. I think that’s a good thing. It’s certainly different. With the Boulder Track Club, that is certainly disheartening because I set the club up in 2010 and we grew and grew and grew. What happens when you grow and have success is that it brings in all different personalities and some of those personalities aren’t in line with what the club’s Mission Statement is or the direction that the club is going. Egos and agendas can be a terrible thing. And I got sick of fighting. I tried to stay on this path and had people who were in the club for the wrong reasons and I had to have a clean break. With the running store, that is a different story in and of itself. It was tough because we were a store in Boulder, and I wanted to go down the path of having my own local, independently owned running store. Unfortunately, I got shafted when it came to that. I didn’t want to be part of a franchise anymore. We had to support the staff and keep the community programs going. And here we are working endless hours. The more money we made, the more money the owners made. I was working eighty hours a week and making no money. I kept seeing other people benefit off my work, so it was time to move on. I didn’t get a say in it. I was forced to close my store. I took some time out to evaluate life, to evaluate me. I was becoming very cynical and was moving into a dark place. I needed to reboot and try to get myself back to a point of loving my own life again before I could even get back into coaching or doing the things I’ve been able to do over the last couple of years.

|

|

| GCR: |

How did the coach-athlete relationship you built with Jake Riley help you both as he rebuilt his training after major Achilles tendon surgery, and you rebounded from the events of 2018? Was it symbiotic as you both rebuilt in different ways together?

|

| LT |

Yes, pretty much. When I had to take my time out, my athletes needed coaching and support crews. A lot of them moved in different directions, which they had to do. There were still a handful of athletes that were sort of hanging around, and one of them was Jake. What I mean by hanging around is that in 2018 we realized that he needed Achilles surgery. Jake had a lot of struggles. He was troubled by the Achilles issue since 2014. He was no longer with the Hanson’s’ team. He was going through some personal things in his situation and he decided he was going to move to Boulder. He had that ‘grass is greener on the other side’ feeling and he moved here. We tried to get him healthy, couldn’t get him healthy and decided he should have surgery. That was in May of 2018 and he was out of commission for several months. Then I’m all over the place and don’t know what I’m doing. By the time he got to where he could start running and make that transition, that was toward the end of 2018 and I decided that I might want to get back into coaching. I talked to Jake and told him, ‘I’m here.’ There were a couple of other athletes too. I was coaching a woman named Carrie Virdon who had graduated from Colorado and taken a year off. I had just started coaching her when all the issues started. I was going through the motions of coaching her. I remember we were out on Marshall Road and it was snowing. It was six o’clock in the morning because she is a teacher. I’ve got my headlights on high beam and I’m following her. Suddenly, I had this epiphany, this moment, when I thought, ‘What am I doing? Here’s this kid who wants you to coach her and she’s giving you what you want. It’s six o’clock in the morning, it’s snowing, she’s out here doing it. Why do I not want this?’ That moment and coaching Jake were the two moments for me when I thought this was what I wanted to do. But I didn’t want to have a group. I didn’t want to be associated with a club. I didn’t want to take any new athletes. I still wasn’t in a healthy head space to do that. I wanted to work with this handful of athletes. Things started to happen. Jake got in more running. He ran a local race the next year. I threw him in the professional race at Bolder Boulder. Then we decided to do the Chicago Marathon in October. Without talking about it, we both knew this is what we needed. We both needed to lean on each other and be with each other because we both had hit rock bottom. We both had been in a situation where we didn’t like where we were, and we wanted to be better versions of ourselves. It was one of those things that got better. The group I had was committed and it was quite therapeutic for me. The success we had grew. Jake ran great to finish ninth at Chicago and was first American. Carrie Virdon got third at the U.S. Cross Country Championships and then went to Canada for the NACAC Championships where she finished second. Then the momentum I built with Jake in Chicago continued right to the Olympic Trials.

|

|

| GCR: |

Can you relate the highlights of Jake’s training that led to his personal best of 2:10:36 at the 2019 Chicago Marathon and then his Olympic Trials marathon buildup, race plan and race execution that put him on the U.S. Olympic Medal podium and a qualifier for the Tokyo Olympics?

|

| LT |

Honestly, we did nothing different after Chicago. The training was basically the same. It takes a lot for someone who has been in a different training environment to change and then to change again. The great thing about Jake is that he doesn’t second guess. He says, ‘I came here and you’re the coach. You tell me what to do and I’ll do it.’ When we went to Chicago, I did what I do, and I like to give motivational talks. I pulled Jake aside the day before and told him, ‘I’d normally do this the morning of the race, but I’m going to do it now. When you’re out there running tomorrow you don’t have to second guess the training which has been great. When you get to 25k, I want you to look around. And I want you to look at who is with you at 25k. There are three questions I want you to ask yourself and the questions are: Can anyone in this group go through what you have gone through? Is anyone in this group as good as you? And does anyone in this group want success more than you do right now? I want you to run with that anger and I want you to realize that no one in that group is going to care about you. Everyone is out there for themselves. Everyone is trying to get a qualifying time. Everyone wants success. You can be friends after the race and friends at the start, but when you get out there and you walk into that amphitheater where the warriors go head-to-head, you must believe in yourself. Once you get to 30k I want you to start to open up and take every step working and forcing yourself on whoever is with you to prove a point – that you are better.’ He went with that. He looked around and went a bit later but that’s what he did like this was his moment and he went with it. When we went to Atlanta, it was a different approach. Chicago was the reintroduction of Jake Riley. He had been injured since 2014 and he had taken five years to get himself back. He had this frustration and anger when he moved to Boulder. He was like me – he had all these bricks on his shoulders. My job was to slowly get these bricks off his shoulders, one by one. He ran with that fire in his belly because his running career had been taken away from him. His thoughts were that it wasn’t going to happen again. When we went to Atlanta, it was like he had achieved, he had answered his critics and the biggest critic he had answered was himself. He was back in good shape. Here was that kid who went to Stanford, that kid who won club cross-country, that kid that went to the Hanson’s’ team, that kid that had the dream of going to the Olympic Games. I said, ‘You’ve got yourself right here. When you get out there to run, it is no longer running with anger. It’s no longer who wants it more. All I want you to do tomorrow when you are in the race and in the closing stages is, I want you to run to it. This is your Olympic dream. You’ve had it for such a long time. You worked so hard and now the hard work is done. I want you to run to it. Run for it. Embrace it. You have a shot at being an Olympic athlete. If you can run freely and with purpose and desire, then you have every shot. Some of the athletes have put so much pressure on themselves that they have already done their racing in their training. Minimize that crowd and you have to do what you can control.’ I gave him the plan of what I wanted him to do and he executed it perfectly. We knew that the weather and the hills were going to take a toll on people and particularly in the last third of the race. I wanted him to be patient. He is an unbelievable racer. He has much more patience and a better temperament than I do. I would always go hard with the pace. He did everything right and you couldn’t write a book about what he has been able to achieve and how he was able to do it. This has been extremely exciting to be that guy who has been in the passenger seat to give him the instructions on what he needed to do and to see him execute.

|

|

| GCR: |

WRAP UP What is your current situation as far as your own running, health, and fitness regimen?

|

| LT |