|

|

|

garycohenrunning.com

garycohenrunning.com

be healthy • get more fit • race faster

| |

|

"All in a Day’s Run" is for competitive runners,

fitness enthusiasts and anyone who needs a "spark" to get healthier by increasing exercise and eating more nutritionally.

Click here for more info or to order

This is what the running elite has to say about "All in a Day's Run":

"Gary's experiences and thoughts are very entertaining, all levels of

runners can relate to them."

Brian Sell — 2008 U.S. Olympic Marathoner

"Each of Gary's essays is a short read with great information on training,

racing and nutrition."

Dave McGillivray — Boston Marathon Race Director

|

|

|

|

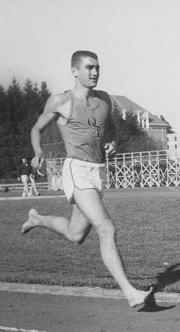

Dale Story led Oregon State to the 1961 NCAA Cross Country team title while also winning the individual NCAA Championship running in his trademark barefoot style. He was the 1962 NCAA 3-Mile Bronze Medalist. Dale’s victories include the 3-Mile at the Far West Relays and 5,000 meters at the Mt. Sac Relays and West Coast Relays. At Santa Ana (CA) Junior College, he won the State Cross Country Championship and State Two-Mile Championship before setting a World Junior Two-Mile Record. He graduated from Orange (CA) High School where he won the California State Mile title in 1959 and broke Dyrol Burleson’s National High School Mile Record by over two seconds in 4:11.0 to earn CIF Athlete of the Year. He won the Mt. Sac Invitational Cross Country Prep Division, triumphing over one thousand runners while breaking the course record by twenty-one seconds, one of thirteen course records he set in high school and college. He earned both his undergraduate and master’s degrees from Oregon State University. Dale’s twenty-nine-year high school coaching career at Wallowa (OR) High School includes coaching thirty-two individual State Champions with seven team State Championships in track and field and two in cross country. His cross-country teams finished top five in the state eight other times. Personal best times include: mile – 4:03.8; 2-mile – 8:46.9 and 5,000 meters – 13:50.2. Dale has been inducted into the Oregon State Hall of Fame and Santa Ana Junior College HOF. He is a lifelong avid outdoorsman with a passion for hiking, fishing, hunting, and kayaking. His competitor, Leroy Neal, compiled Dale’s stories into ‘Dale Story: NCAA Cross Country Champion, Educator and Mountain Man,’ which was published in 2017. Dale’s life accomplishments were achieved after contracting polio at age eleven, being paralyzed from the neck down and bedridden for seven months. He resides in John Day, Oregon and was most gracious to spend over two hours on the telephone for this interview.

|

|

| GCR: |

THE BIG PICTURE As you look back on your running career and the solid years of strong training and racing, how exciting was it to be putting in the hard training and racing and pushing yourself to try to reach your ultimate best in terms of times and competition?

|

| DS |

It was a struggle because I always had a little doubt in the back of my mind as to how well I would do. I wasn’t terribly oozing over with cocky confidence. It was a way of my trying to come out of a ‘little man complex’ because I was a little guy. Also, since I had polio when I was eleven years old, it was a bit of a struggle to get notoriety as a human being, as a young buck. But I loved to run. Running across the earth wearing just a pair of running shorts made me ecstatic. It was like I was an antelope, and nothing could stop me.

|

|

| GCR: |

In distance running, when we look at our running careers or others review our accomplishments, we are usually measured by championships, honors won, and fast times. Back when you were running, careers were usually shorter since it was before professionalism extended running careers. What does it say about your success when, in the five-year period from 1959 to 1963, you broke the U.S. High School Mile Record, were CIF Athlete of the Year, broke the World Junior 2-Mile Record, led Oregon State to the NCAA Cross Country team title while winning individually, and were the NCAA 3-Mile Bronze Medalist?

|

| DS |

I didn’t appreciate that until I was quite a bit older in my forties. I struggled with the idea of never getting to the Olympics and never even trying for it. I would look back at my defeats and they would bother me. But, later as I matured and had more experience with other people’s lives and from reading books like Kenny Moore’s book on ‘Bowerman and the Men of Oregon,’ I began to realize that all those great athletes didn’t have perfect days all the time. There were times when they didn’t make it. Bill Bowerman, himself, said there were days when everything clicks. I didn’t realize that until I was older, and I began to appreciate what I did. I thought, ‘You didn’t do too badly.’ I have a friend who says we have to get rid of our ego. But, if we do, what gets us up in the morning? We have to have something to look forward to.

|

|

| GCR: |

Most of us have mentors that help mold us along the way. Through your career, what were the primary elements of training, racing tactics, and mental toughness you learned from each of your coaches, Orv Nellestein, Big John Ward and Sam Bell, that developed you into a top competitor?

|

| DS |

I don’t want to take anything away from my coaches, but I was self-motivated. I read everything I could get my hands on about running – Emil Zatopek, Herb Elliott, Percy Cerutty and Arthur Lydiard. So, I was already destined to do something, whether it was the right way or the wrong way. Orville Nellestein was a great guy from the standpoint that he recognized I was well-read. He gave me a tremendous amount of freedom to train as a high school athlete. What he did for me was to protect me from the news media. They were voracious. They wanted predictions of the National Record in the mile, and I didn’t like that. I didn’t care for that very much. It was added pressure and I was already putting enough pressure on myself. He was very good about that. Big John Ward was like my father, because my father had left when I was five years old. When I was going to go to junior college, all these other coaches were trying to recruit me to break this record and that record. Big John said to me, ‘Hey, do you want to go fishing?’ He must have got an ‘A’ in psychology. He knew me well and we went fishing two to three times a week. He was out for me. He wasn’t out to put a feather in his cap and I appreciated that. He was a great guy. At the NCAA meet, I remember putting him in my mind and thinking, ‘Big John, this one’s for you.’ Sam Bell was a very, very nice guy. He was kind of young when he coached us and wasn’t totally realistic in his training. He would start us out way, way too fast. The team had injuries, but I didn’t because I kept in shape all year around with my outdoor activities. Sam was a heck of a man and he would do anything for us. He was quite religious. I had the utmost respect for him. I do remember when I set that World Junior Record two-mile record of 8:46 that the next Monday Sam called me into his office. He said, ‘Dale, you know you can break Albie Thomas’ World Record in the two-mile?’ At that time, his record was eight minutes and thirty-two seconds. I walked out of there as a young nineteen-year-old buck thinking, ‘You’re not realistic. That is a lot to knock off.’ But, as a coach, you must set high sights. The question is, ‘how high do you go?’ Different athletes have different potential, and you may not know what that could be. Steve Prefontaine would have probably looked at him and said, ‘Okay, I can do that.’

|

|

| GCR: |

Competing is often a roller coaster of great results, mediocre races, and poor efforts due to overtraining, undertraining, and trying to find the perfect place that has us treading the fine line between improvement and injury. How tough was it for you to find that balance that led to peaking at the right times for your most important competitions?

|

| DS |

That is a tough question to answer. I don’t think I did that good of a job at that. My problem was more mental, and I don’t mean weak on the track. But to do the training for the long distances as opposed to going on trips to Canada and getting in my kayak and going two and three hundred miles on a trip took time away from training. That is why I didn’t get to the Olympics. I was torn between two major loves – running and the outdoor wilderness travel. So, which one do I do? Right or wrong, I made the best decisions I could. That was a tough one. I loved to be in shape. I was always concerned about not overdoing it physically. It was kind of like Bill Bowerman’s philosophy that you remain sharp by not overdoing your training. Ron Larrieu was overtraining. He was an incredible runner, but he was beat up physically. And there were several other guys who did that. I was worried about that when I was young. I thought that I shouldn’t overtrain. I wanted to make training fun and mentally exciting, so I put in fartlek and beach running and river running and mountain running and intervals. When I coached, I took the kids up in the mountains and the hills. Sam Bell didn’t do that. And we did repeats on the coastal plains on the steep hillsides. I mixed it up all the time.

|

|

| GCR: |

Just this morning I was listening to an old interview from 1974 that sports broadcaster, Howard Cosell, conducted with former Beatle, John Lennon, that has an interesting concept. John Lennon said that as a solo artist he got to the point where he was writing and was overthinking what he was trying to say. So, he had to quit overthinking and let it flow. This reminded me that often we are overthinking our running training and racing and don’t just let it flow. Could this prevent us from being our best and possibly limit our outcomes?

|

| DS |

I think there is a lot to this. For example, when Tracy Smith came to Oregon State and I was finishing up, I tried to take him duck hunting and he didn’t want to go. I tried to get him interested in girls and he didn’t show any interest, though he was a handsome guy. All he wanted to do was run. I worked with him in a couple of classes because he was a Fish and Game major, and he was not that interested in academics. I said one day, ‘Tracy, you’ve got to have some other outlets because if, for some reason, you get hurt or have an injury or a down season, what do you have to fall back on?’ Shortly after that he got injured and left. Fortunately, he gathered himself up, went to Southern California and ran very, very well. That was an example of someone who was a hundred and ten percent running.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned your outdoor activities and, from reading your biography, you are an outdoorsman who, during your life, has enjoyed hiking, camping, hunting, fishing, kayaking, and running in undeveloped forests and country. How did your love for a variety of outdoor activities help you to love running but also to hurt your ability to give necessary focus to running for as many years as other top-notch runners often do? But was that okay because, if all you did was running, maybe you wouldn’t have been as good because your life would have been unbalanced?

|

| DS |

You are absolutely right. And how can we second guess what we did twenty, thirty or forty years ago? At the time we make our best judgement, whether it was you or me or anybody else. With all the information we have at our fingertips, we make the best decision. We wouldn’t purposely make a bad decision. Then thirty years later we look back and things have changed so we might beat ourselves up somewhat. I did that when I was in my thirties and then I came back and said, ‘Dale, at the time you did the best you could.’ You never know.

|

|

| GCR: |

You talked about your barefoot running and you are one of very few elite runners who competed primarily barefoot. What did you gain from the strengthening of your feet, being in touch with the earth, which Lorraine Moller from New Zealand spoke about with me, and possible psyching out your opponents?

|

| DS |

It could be all three of those. I was raised in southern California, through no choice of mine, but the weather was conducive to being barefoot. The only negative was the goat heads I would run through occasionally. Those are big stickers and are voracious and tough. I could just jump up in the air and knock them off my feet because my feet were very calloused. Now, at seventy-nine years old, if you ask me if I have arthritis, the answer is yes. Is it just in my feet? No. I don’t know whether the arthritis is due to old age, how I treated my body or a combination. There is no way of knowing. When I was running, I felt free. I didn’t like cumbersome clothes. I didn’t even wear a singlet when I was running in competition in high school cross country. We could get away with it. I wore a pair of running togs and that was it. Being free with the earth is definitely a good argument for running barefoot. And after a while, it might have been subconscious that I was looking for attention. It was something that was unique. I don’t know the answer to that, but I will say that I probably got fifty percent of my accolades from running barefoot.

|

|

| GCR: |

Since you had success racing the mile and breaking the high school record, in the 2-mile breaking the World Junior Record, in the 3-mile with a Bronze Medal at NCAAs and 4-miles cross country where you won NCAAs, what is your favorite racing distance and why is that so?

|

| DS |

In the early days in high school in California, the mile was the longest distance we raced. I had to get special permission to race the two-mile in a Claremont College track meet. I won the race, and my time was only half a second or three-quarters of a second off the National Record. I loved the two-mile but wasn’t able to run it again in high school. When I went to Junior College and won the State two-mile and went to Oregon State, we probably liked the race where we did the best. I always loved the 880. I ran a 1:52.6 on a relay, a four-man two-mile relay at Mt. Sac when I was in high school. I wanted to run it more, but everybody had me labeled as a miler and two-miler, so I stuck with that. I always wanted to drop down and see how fast I could go. I loved just grinding it out on a track. I never tried the 10,000 meters and I wished I had done that. I loved the continual pace. And varying the pace was critical. That’s where Gerry Lindgren could do so well.

|

|

| GCR: |

From your years of racing and training, who were some of your favorite competitors in high school and college due to their ability to give you a strong race and bring out your best?

|

| DS |

Leroy Neal was a tough cookie in California high school track. He beat me for the first three years and then I beat him the next few years. He’s the one who wrote my biography and is a great guy. He pushed me a lot. Jack Hudson, who got second to me in the mile was a tough cookie. He was tough. I was always ready for Jack. He frightened me because he had been running very fast. He could run a 1:53.8. The other one was Keith Forman at the University of Oregon. He was a very nice guy. I’m not attracted to cocky, arrogant runners, even though they may be good. Keith Forman was a real gentle man on the track and a tough competitor.

|

|

| GCR: |

When you look back on your years of racing, you won numerous times on the track and in cross country. No matter how big or small the field, or strong the competition, was it always exciting and satisfying to be first across the finish line, to break the tape, and to set over a dozen cross country course records?

|

| DS |

I kind of forgot about that, but somebody who was doing the research told me I set thirteen cross country course records. I said, ‘thank you, that’s a nice feather in the cap.’ I absolutely loved to win. There is no way around it. Winning strongly motivated me. In fact, just a short while ago I was listening to music I listened to before a race, Maurice Ravel’s ‘Bolero.’ That was also used as the background music in the Bo Derek movie, ’10.’ I would stand in front of the mirror in my running gear and visualize the race. I would run in place and listen to the music. I’d pick up the tempo and visualize myself winning that race and being so strong and powerful that nobody could beat me. That didn’t always work but it worked a few times. It was a big thrill to win. I didn’t brag about it, but deep down inside it meant a lot. I was a little guy trying to prove myself. We don’t always have success, but if we hit a few high points it is great. I was thinking about this recently and the biggest thing is what we pass along to the young bucks, the guys who are reading about us. It’s like I learned from Emil Zatopek and Herb Elliott and Peter Snell. They were my heroes and I found out as a little kid that I would like to do that. Then what I did was to break the ice for the young bucks and that’s the part I liked. I appreciate that now just as I do you taking an interest in me at seventy-nine years old. It should be the undertaker calling me!

|

|

| GCR: |

When your competitive days wound down, you graduated from college and earned your teaching certificate, and transitioned to coaching others on the high school level. What were the most important factors you learned from your own training and racing to help them to move to a higher level of maximizing their improvement and minimizing their injuries?

|

| DS |

Over the years I heard many times from my athletes that we always peaked at the right time. Keep in mind that I coached at a small school with a very short cross-country season. We were only able to train two-and-a-half months. Many of the other kids played football. I told the kids I didn’t care about the early meets as long as we learned something every time we ran. We wanted to be hitting our best at the end and we did frequently. I told them we want to progress at a normal rate and not get carried away. Other people thought we had to win this relay meet or that meet. We didn’t do that and that is why we were able to be successful. My kids told me that one thing they liked about me is that I was an inspirer. I could inspire them. It may not have been my training techniques, though I had read quite a bit and done well. I emphasized the mental aspect of the race and the mental aspect of training and they told me that was one of my strong points – the ability to inspire people. That may have been by chance, but what I did have was enthusiasm. I was never sitting up in the stands. I would be out on the track moving around with the athletes and I could yell loudly. That might have been terrible coaching. I don’t know. But it worked.

|

|

| GCR: |

We briefly spoke about your book, which was written by your friend and your competitor, Leroy Neal. He collected many of your stories which were published in 2017 as ‘Dale Story: NCAA Cross Country Champion, Educator and Mountain Man,’ Did the book effectively capture these three aspects and facets of your spirit and are you pleased with Leroy Neal’s effort?

|

| DS |

Yes, and I was reluctant to do this. Jan Underwood, who is a buddy of both Leroy and me and who was a fantastic 800-meter runner in high school in college was with Leroy and me and they were talking about a book about me. I told them I didn’t want to do it. But they told me I could influence a bunch of young kids if we wrote the book. So, I went back and thought about it and that maybe they were right. That was my decisioning factor. I told them whatever was done that the book has to have no crap in it. Just expound on anything, just tell the truth. That’s what I tried to do because that has been a mantra of mine. Let the chips fall where they may. Leroy might have got a little wild when he called me ‘The Mountain Man.’ To me, the mountain men were Jim Bridger and Jedediah Smith and Hugh Glass and Lewis and Clark. I never stood up to those boys. But in the 2000s, you might call me a creature like that.

|

|

| GCR: |

COLLEGIATE RACING You began your collegiate running at Santa Ana (Calif.) Junior College, where you won the State Cross Country Championship. What do recall from that race as to your competition, the terrain and when you made your move to secure the victory?

|

| DS |

Our team was extremely dedicated to our coach, Big John Ward. He was a father to me and many of the kids, but especially to me because of our connection with hunting and fishing. We wanted to win that baby for him, and we worked together. I thought, ‘I’m doing this for Big John and my teammates,’ We ran at Glendale Community College. I always went over the courses beforehand and memorized them very well. There were a couple spots where we had to make a sharp left-hand turn, almost ninety degrees. That is a spot where you can get out of sight. When I was leading, I knew the next runner knew I was ten yards ahead of him. I’d go around the turn and sprint like a madman, like Lindgren. I would try to do it relaxed, but while moving solidly. Then when he comes around the corner, I’m twenty yards ahead. I had been only ten yards ahead, so now I’m starting to work on his brain. And he’s starting to think, ‘Well, maybe I’ll settle for second place.’ At least that was my theory. Anytime I ran and there was a blind spot, I would crank it up. Whether it was going up a hill or around a blind corner, that was the strategy I was using then. I used that a little also in high school.

|

|

| GCR: |

That spring you set a World Junior Record in the two-mile and won the State two-mile title. What were highlights of those races and how did you find the step up in distance from racing primarily the mile in high school and your unfulfilled desire to race the half mile more frequently?

|

| DS |

I wouldn’t have been that good of an 880 runner. I would have been decent, but not great. I was sticking with a distance where I could do well. That’s probably why I was more successful in the two-mile than the mile. I remember one time when I was training for the two-mile and three-mile, the coach put me in the mile down at Occidental and came by the three-quarter mark at 2:59 and was in the lead. I was flying high and thought, ‘I can go under four minutes! This is it!’ The last lap was consistently my strongest and I made a huge mistake. I made my move right then with 400 meters to go. Not a good idea. I should have floated like a butterfly, like Muhammad Ali, and maintained my pace. But in the last seventy or eighty meters the old grizzly bear jumped on my back. I was very dejected. I never did run the mile anymore after that. It was always the two-mile, three-mile and 5,000 meters. Later, I got to thinking, ‘Could I have done it?’ Deep down inside, I think I could have. But, anyway, I didn’t do it.

|

|

| GCR: |

You had the opportunity to finish your collegiate education and running at Oregon under Coach Bill Bowerman or Oregon State under Sam Bell. What were the factors that led to you choosing Oregon State and do you ever wonder what may have turned out differently if you went to Oregon and the guys you raced against were your teammates?

|

| DS |

I was limited in my choices because I was a Fish and Game major and very few colleges had that major. I passed up the University of Utah where I could have had a full ride. But no good runners were coming out of Utah. I don’t know if it was coaching or altitude or some other factor. Sam Bell was recruiting me when I was in my last year of junior college and was sending me workouts which I thought was kind of inappropriate because I was training under Big John Ward. I wanted to run for Bill Bowerman at Oregon, but they didn’t have a Fish and Game major. It was a no brainer. I had to go to Oregon State. And to speculate how I would have done at Oregon – I don’t know. There would have been more competition on the team. But I created my own competition when I went to big meets. You don’t have to wear the yellow and green. You can go to Modesto and other meets and run against some good runners. I do remember respecting Coach Bowerman and I wrote him a letter after he retired. He was very thankful. Some friends of mine told me that Bowerman was tickled to receive my letter. I was not a Duck. I was a Beaver, but I appreciated what he did.

|

|

| GCR: |

Your break-out race nationally was when you finished seventh at the 1961 NCAA Track and Field Championships in Philadelphia in the 3-mile in 14:38.6, a few seconds behind Steve Tekesky from Miami of Ohio and John Macy of Houston. How did that race go strategically, and did it leave you hungry to do better the next year?

|

| DS |

I’ve got a huge explanation for that race. It is embarrassing and almost criminal. This was the race where the NCAA top six qualified to go to New York to run in the AAU meet where the top six would qualify to run internationally. The first two there would run in the US-Russia meet and the next four would do the European tour. I believe I had one of the fastest times at three miles and 5,000 meters. I was already all set to go to Canada for kayaking with my buddies for hunting and fishing and exploring some wilderness. I didn’t want to go to Russia. I didn’t want to go to Europe, and I threw that race. I tried to make it look like I started my kick too late, which I never did before in any races. I was always up in the pack and was awake and cognizant of what was happening. Coach Sam Bell never said a word to me. He gave me my plane ticket back to Oregon and I don’t remember if he even said goodbye. I thought that I wasn’t a slave and didn’t have to run for anybody and I wanted to go and do my thing. I guess I could have run my best and backed out of running in New York. That was terrible. It was like throwing a football game. It was absolutely criminal, but I don’t mind telling you because it is the truth. It tells you how strong the strength of that magnet was pulling me toward the wilderness.

|

|

| GCR: |

After your summer of a combination of training and outdoorsmanship, you came into the 1961 cross country season where Oregon State, amazingly, only raced four meets. What do you recall from your second place run at the 1961 Pacific Northwest AAU Cross Country Championship in Seattle?

|

| DS |

I think that is the one when Dyrol Burleson beat me. I didn’t like the result, but it was my fault. I don’t remember any details of that race. It was on a golf course park and the grass was wet. In Oregon, it’s always wet. We were together and he outkicked me.

|

|

| GCR: |

Let’s discuss the 1961 NCAA Cross Country Championships in some detail. First, since there were no qualifying events, were Coach Sam Bell and your team fortunate that Athletic Director Spec Keene sent you to the race at all?

|

| DS |

I was surprised we went to the race, but I thought, ‘This is good competition.’ I never did analyze that much, but when I stop and think about it, that was quite unique. Spec was a very nice guy and Sam got along good with all the administrators as far as I knew. But that was out of my realm. I just thought this was the way it was done, and it was fine. I was elated that we had a chance to run and am sure glad. The rest of the team pulled great with their contributions. We scored sixty-eight points.

|

|

| GCR: |

During the first half of the four-mile race, you bided your time behind leader, Don Metcalf of Oklahoma State. Were you feeling strong and in control in the cold weather and running barefoot on a surface that had some twigs and acorns?

|

| DS |

I felt very strong. The only thing that bothered me was we had a hundred and thirty-four runners and, after the first ninety meters, we had to go through two gates. The gates were eighteen feet apart, or something like that. We had to funnel all of those humans through those gates, and I thought, ‘There is no way I can be back. I’ve got to be in the top five coming through that gate.’ I was in the top two or three. That first quarter mile was quick. It was under sixty seconds. And I didn’t like that. I hated that. But that was what we had to do. Then when we got around that gate things started to smooth out and I felt very good there. I stayed up in the lead group because I didn’t like to be in the back. If you get in the back, there is too much work to pass all those guys and you have a greater chance of getting spiked, your hip kicked, slowed down or whatever.

|

|

| GCR: |

How did it transpire that Finland’s Matti Raty, running for Brigham Young, and you took off about halfway through the race and separated from the remainder of the field? Did you work together and figure you’d settle the Gold and Silver Medal later in the race?

|

| DS |

He was a nice guy and a nice-looking kid. He pulled up on me about halfway and we looked at each other. He said something to me. He started it and I said, ‘We’ll work together.’ And we did. He was strong, and I started thinking, ‘This is not going to work because I want to win this race.’ I couldn’t be friends with him forever. I didn’t know at the time he was from Finland, so I could help with international relations. He didn’t talk about settling the medals, but I was thinking it big time. Running with him helped. He would look back and say, ‘They are thirty or forty meters behind.’ I never had a race where I worked together as a team with a competitor.

|

|

| GCR: |

What were the moves you made that allowed you to open a gap on Raty that grew to your eleven second winning margin?

|

| DS |

I knew that hills were my absolute strength. When we got to this hill, I just burned. I think I might have dropped hm back a little bit before the hill, but the hill was a determining factor.

|

|

| GCR: |

What was the feeling when you crossed the finish line ahead of a stellar field that, when we look back years later, ended up including over a half dozen future Olympians?

|

| DS |

I didn’t know about how these runners were as far as the Olympics at the time. I knew there were some tough runners. I didn’t know about Al Lawrence and Pat Clohessy that much. I was very elated for my coach, Big John Ward, even though he wasn’t there.

|

|

| GCR: |

Moving ahead a few months to the 1962 Outdoor Track season, I was fortunate to review a scrapbook that Oregon State has in their digital archives. First, when Oregon State met Occidental you had a close battle in the mile against Leroy Neal of Occidental, nipping him 4:09.3 to 4:10.9, before you won the two-mile by twenty-six seconds in 8:46.9. What do you recall of that close mile battle and then of focusing on maintaining your pace in the two-mile when no one was close to you?

|

| DS |

I remember racing against Leroy Neal big time. Back in high school we were on a tough course with a narrow trail along a steep hillside where we had to run single file. Somehow, Leroy got ahead of me and a branch came back into my face. To this day, I don’t know if he purposely knocked the branch back into my face with his hands as he went through or if it was purely accidental. I’m leaning now to believing it was accidental but, at the time, I thought it was on purpose. When we got down to the track toward the finish there was this girl that I thought was his girlfriend cheering him on with a hundred meters to go. I didn’t have a girlfriend and she was cute. So, I waited and turned and looked at her and winked. Then I sprinted past him in front of his girlfriend for humiliation. Now, that’s terrible sportsmanship (laughing). Years later, I told him about that, and he said it wasn’t his girlfriend. But I don’t remember detail about the meet you mentioned.

|

|

| GCR: |

In a Tri-meet with Arizona and Arizona State in Tempe, Arizona, you won the mile in 4:08.3, eight seconds ahead of Jack Hudson, who finished second to you at the 1959 California State High School Championships. Did the two of you have any friendly conversations or jog a bit together in the warmup or warm down?

|

| DS |

Jack and I weren’t close friends and I was, for the most part, a loner. I didn’t socialize like many other athletes. With the runners I liked, I did socialize. But Jack was not my kind. I remember that meet and I was surprised to beat him by that much.

|

|

| GCR: |

As the season progressed, you won the Far West Relays 3-mile in 13:50.2 with a last lap kick to pull away from Oregon’s Mike Hehner and Keith Forman and followed that race the next two weeks with two-mile victories against Washington and in a triangular meet at Berkeley. Did any of these races stand out or were you just building for the important season-ending meets?

|

| DS |

I remember the races, but not in depth. We ran so many races so, if they weren’t spectacular, I didn’t spend much time thinking about them other than what I learned during the race. I’ll tell you one thing – Keith Foreman always kept me on my toes. He was not only a nice guy, but he was tough. One time we ran in a race at Oregon State and we traded the lead I think four times on the last lap of a two or three-mile. I’d go by him and he’d go by me and I didn’t let up. He just had so much energy. I ended up winning the race, but I thought, ‘Man, oh man. I’ve never been challenged by anybody like that.’ It was technically a lot of fun, only because I ended up being victorious. Had I not, it probably wouldn’t have been that much fun to have a challenge.

|

|

| GCR: |

In late April of 1962 you moved up to 5,000 meters and won the Mt. SAC Relays in 14:06 over Charlie Clark, Julio Marin and your teammate, Bill Boyd. You followed up two weeks later by winning the West Coast Relays in 14:06. Do you recall much from those two efforts?

|

| DS |

Oh, yes. Now you’re getting into more prestigious performances. For the race at Mt Sac, I had trained very, very good and had one series of repeat three-quarter miles that I ran with a quarter mile shag in between. I started out with a 3:21 and ended with 3:09. I got done with that and thought, ‘Hey, I’m ready. I’m pretty strong.’ Mt. Sac was always a fun meet to run in. When I was in that race, with about three laps to go, I cut loose with about a sixty-two second quarter which was quite a bit faster than what we were running. And nobody went with me. Nobody. I trained trying to do that. Now, I knew I had to maintain my relaxation and composure and make sure they didn’t draw back into me. They all were wondering what I was doing, but I ended up winning. I didn’t tell them afterward that I wanted to break their spirit, but it did work. Then at the West Coast Relays, I was running barefoot on the track with Julio Marin. He was from Puerto Rico and running for USC. It was probably about two miles into the race and, I’ll be damned, if he didn’t spike me. I went down on the track and I thought, ‘He and I are in the lead. There is nobody with us and we have a sixty, seventy or eighty-yard lead. There is no reason for this. When I went down, I rolled and got back up. And I was angry. I ended up beating him. I had to get stitches because it was a puncture wound. They had to drain it and put in a couple stitches because it ripped a little bit. I was mad. I didn’t even know the guy and I told him, ‘Julio, if you ever do that to me again, I will kill you.’ I looked him right in the face and said, ‘I will kill you.’ I believe that he remembered that because he never did get to close to me ever again.

|

|

| GCR: |

You finished in Bronze Medal position at the NCAA 3-mile, seven seconds behind Pat Clohessy, four seconds behind Brian Turner and four seconds ahead of Pat Traynor. Can you describe how the race progressed, crunch point moves that were made and if you felt you ran as strong as you were capable?

|

| DS |

If I could have won the race, I would have done it. I do remember feeling terribly strong with maybe one lap to go. I was in the lead and feeling strong and knew I had a good kick. By God, here Clohessy comes by me and I never let anybody go by me with the idea that I’d catch him tomorrow. When somebody goes by me that close to the finish line, I’ve got to be with them. Contact is absolutely essential. In the future when I was coaching, I always told all my runners to stay eighteen inches off their body unless you want to do something very strategic. But he went by me and then coming off the turn, here came Turner. I tried to hold him off and just couldn’t. That was very embarrassing. It was a hot day and very salty, but I’m not blaming the weather, though that is the only mitigating factor I can surmise. I remember after the race walking right into the metal timers and judges stand. It was a vertical stand about three tiers high for all the judges and timers to stand on. I walked right into that and hit my head. I thought, ‘What the hell?’ It didn’t knock me out or anything, but it was a good little whap. I think that was one of those days when my physiology didn’t all fit. That was one of the deepest wounds I carried, and I still do. To get third in the NCAAs when you have the fastest time. Come on. That’s a breakdown. It just didn’t work that day. I can accept that now. Who cares at this point?

|

|

| GCR: |

Many of the track and field stories I reviewed in the digital scrapbook I mentioned were in ‘Rick’s Ramblings’ by Jack Rickard, the Gazette-Times Sports Editor. How great was it to have so many great teammates like the mile relay quartet of Lynn Eaves, Gary Comer, Bob Johnson and Norm Monroe, pole vaulter Jerry Betz, multi-event jumper Jim Roehm, middle distance runners Norm Hoffman and Morgan Groth, javelin thrower Gary Stenlund and such a strong interest in the Oregon State track and field program by the local newspaper and Mr. Rickard?

|

| DS |

That was great. Back in those days in many dual meets we could even beat the University of Oregon. But it would almost always come down to the mile relay. Unfortunately, as a distance runner I couldn’t contribute. But guys like Bob Johnson and Lynn Eaves could run two or three events. It seemed like it would come down to that mile relay and we would be behind, maybe by twenty-five meters. My buddy, Jan Underwood, who is still one of my best friends, grabbed the baton in one meet and took off. He caught them at the top of the curve, and we won the meet. I just talked to Bob Johnson yesterday. Lynn Eaves, the Canadian sprinter, is down in Arizona right now. We had a nice conversation recently and are going to get together soon. Jerry Betz, unfortunately, died a short while ago. But it was neat to have the coverage in the paper. The big meet was at Modesto Relays and Oregon State was on fire in 1962.

|

|

| GCR: |

One thing I find to be interesting was how important the dual meets were back then. One that was amazing to me was, that in 1962, Oregon State dominated against Washington and won 104 2/3 to 39 1/3. It was a big beating and the story noted it ‘avenged the 1938 beating when Washington won 99 to 31.’ So, the sportswriter went back to note the win was payback for twenty-four years earlier. Isn’t this a great example of the importance placed on these dual meets?

|

| DS |

They were very important. I didn’t pay a whole lot of attention to that though, unless the team was fired up. I was mainly concerned with my race and what I could do to help the team win. The meets were big and sometimes when I was really turned on, I asked the coach if I could run the mile and two-mile to score more team points. I didn’t double as much as some athletes who doubled much more frequently.

|

|

| GCR: |

EARLY DAYS IN RUNNING AND TRAINING Before you started organized running, did you compete in a variety of sports as a youth and how did you get started running cross country and track and field?

|

| DS |

That’s an interesting question and I have an easy answer. I was the fastest kid in elementary school in fourth and fifth grade. Then I contracted polio at eleven years old and I couldn’t run, couldn’t walk, and couldn’t move my body from the neck down. That was about seven or eight months until I started a long recovery process. I couldn’t even take P.E. class. A couple years later I came into my freshman year of high school in 1955 and the cross-country coach, who was also the music teacher, said we were going to have a race to see what the school had in terms of runners. I asked if I could run and he said, ‘No, you’re too little.’ I asked a second time if I could run, and again he told me I was too little. I was five foot, two inches and eighty-nine pounds. I had some muscle atrophy because I couldn’t develop when I had polio and then the recovery period. I begged him the third time and, finally, he let me run. In a school of almost two thousand kids, I beat every runner except one senior. Then the coach sang a different tune. But I never respected that guy from then on and did not like him. I saw him later and he never apologized. He was eighty-something years old and he never said anything. I thought, ‘Okay, that’s your problem.’ But that was a good lesson for my because, when I started coaching, no matter what a kid was like or if a kid didn’t seem to have much physical promise, I never discouraged them. I remembered what was done to me and knew it wasn’t a good idea. You can’t break the human spirit because it is strong.

|

|

| GCR: |

You were fast early on and ran a 4:32 mile as a sophomore. What were some of the highlights of your training and racing during your first three years of high school?

|

| DS |

There were so many other good runners ahead of me. All I could do was to just climb up the ladder. Each time I kept copious records in my scrap book, and I kept reading everything I could about running. I wasn’t in a big hurry, though my junior year I had the fastest time in California in the mile. I ran a 4:21.6. There were quite a few qualifying meets to get to the State meet, the CIF Finals. For some reason – I don’t know if I was overconfident as I was always awake in the race and knew what’s going on everywhere – I started my kick a little bit late and I got fourth place by one inch. I didn’t get to State though I had the fastest time in the State of California. I walked off that field and, I’ll tell you, if you saw what I did you probably would have called 911. I was bawling like a little baby. I went over into a field totally by myself, cried my heart out and made a vow to myself this was never going to happen to me again. I was going to come back so strong that I was going to kill everybody. I don’t mean that violently. I was going to win the races. The next year after every workout, no matter what it was, I would run ten one hundreds with a thirty-meter jog rest in between. They were full bore, as hard as I could. My legs were tired and full of lactic acid. I was in oxygen debt, but I wanted to do everything I could to build my kick and make sure I was terribly strong. My senior year the opening race in our first meet was an 880 and I ran a 1:58.1. Before that, I had only run a 2:05 so I knew something was working. My senior year we had twenty-three track meets. We started in February and finished up May 30th. I told coach that I didn’t want to run the mile every time. I only wanted to run the mile in the big meets with good competition where my chance of success was great. And he said that was fine. So, I would branch off and do 440s, 880s, 1320s and always run the sprint relay. When I did run the mile, the 880-yard relay was right afterward with no races in between. I would run the second or third leg on that breathing hard after my race with lactic acid in my legs and little rest. I knew it would help my kick and it worked. I only ran eleven mile races that year. I ran other distances in the twelve remaining meets. Some of the guys smoked me in the shorter races, but I was working hard. In February I ran a mile in 4:19 anchoring a distance medley relay and it was easy. I went home that night, put my running gear on and ran out in the orange groves and hills and said to myself, ‘I know I can beat the National Record.’ When I was a sophomore, I saw Dyrol Burleson’s picture in Sports Illustrated when he broke the National Record and I thought to myself, ‘That is inhuman and impossible.’ And it was as long as I thought that way.

|

|

| GCR: |

Let’s talk about three of those mile races. First, Dyrol Burleson’s national high school record was 4:13.2 and you came close at Compton in 4:13.4. What can you tell me about that race in terms of leading, following and how cognizant you were to the near-record pace?

|

| DS |

That was at the Compton Cup meet which was a prestigious meet on a clay track. Everybody they invited for the mile race were the best in California. I knew that at a night meet the speed was there because of the darkness, cool air, and different environment. I had my buddy over there at the 220-yard mark giving me splits and he read the split wrong. I was in last place with seven guys ahead of me. I thought I was doing fine, but I came by the first quarter mile in sixty-seven seconds. Good Lord – that was atrocious. My coach yelled, ‘Move!’ And I passed all seven of them. I went out to lane four or five on the curve and passed all of them. I ran the next three laps in sixty-three, sixty-two and sixty-one. That is why I missed the National Record by two tenths of a second. I wasn’t trying for the National Record. I wanted to win the race. I knew that sixty-seven was atrociously slow, but after that race I knew I had a chance for the record.

|

|

| GCR: |

At the 1959 Southern Sectional Meet you set a meet record of 4:16.9 in the mile with Jack Hudson of El Cajon and Jim Pederson of Arcadia in second and third place. Did your previously run 4:13.4 give you the confidence that you were the one to beat and how competitive was your duel with Jack Hudson?

|

| DS |

The local newspapers thought I could break the National Record and they kept putting tremendous pressure on me to get it. I didn’t fall for that. My own idea was that I would do it in due time and, if I did I did, and if I don’t it wasn’t a major thing for me. But I wasn’t one of these guys that would just win in mediocrity. I wanted to win, but I wanted to win fast. Breaking the National Record was an added pressure. I remember one race my junior year with Jack Hudson because he had beaten me badly before. It was a big relay meet in Huntington Beach, California. I saw him in the rest room before the race and he said, ‘I’m going to come by the three quarters in 3:10.’ I said, ‘Good, Jack. I’ll be right behind you.’ That was the first time I got cocky. I found out later that he was throwing up in the locker room. Whether that was coincidental or nerves, I don’t know. But we were in the race and he was in the lead. With three quarters of a lap to go I pulled up on him to pass him and he starts to speed up, not too much, but just enough. I immediately let out a grunt like I was out of wind and I dropped back behind him. He thought he had broken me, but he hadn’t. I slipped in behind him as quietly as I could be, tiptoeing along. Then with two hundred meters to go, whoosh, I went past him and broke his back and he never beat me after that. It was a psychological deal with him. It was like Muhammad Ali would do, and I’m not trying to get in his category. A little fake – I like playing that way. I raced fair, but it was always fun to work on somebody’s brain.

|

|

| GCR: |

At the California State Championships you raced 4:11.0 to win and break Dyrol Burleson’s National Record of 4:13.2. Can you take us through the race where Jack Hudson set the pace and you went through laps of 62.6, 62.6 and 66.1 before a monster 59.7 last lap led to a five-second victory over Hudson?

|

| DS |

At the meet I knew it was my last chance for the National Record and that was added pressure. We were having dinner with my mother and my brother and I couldn’t even hang around and had to leave. There was a little mental pressure. I went out on the field and was a little nervous. I remember stepping out on the field with these ugly, faded, red sweatpants I always wore. They were so faded that you couldn’t even tell they were red. They were so old. I never liked to be identified as a fancy athlete. Then as soon as I stripped off my gear, boom, suddenly, I have a seventeen-year-old, tanned body that is ready for warfare. As soon as I got out there and as soon as I peeled my gear off, I was so relaxed. It was close to ten o’clock at night and I thought, Okay, this is it. Let’s do it.’ I was pretty dang confident. Of course, with Jack you had to be concerned because he was tough. Since I knew he liked to take the lead, that was okay because I liked to follow. I’m talking about eighteen inches behind, right off the left shoulder so he knows I’m there. But I’m poised to attack, even if I have to run a couple inches longer out in lane one-and-a-half. That’s still okay. I remember always trying to take that last lap. I started cranking it up with 500 meters to go. I usually did with a quarter mile to go. I always tried to do that in training very quickly, but with a minimal amount of effort. Leroy Neal got a copy of that State meet film that someone put on a DVD, though there is no sound. I was looking at it with my granddaughters and said, ‘Here’s your grandpa. He could run a little bit.’ I was amazed at how quickly I accelerated. I kept looking at my arm drive and my legs and I thought, ‘How did I increase my velocity that much?’ It was just in a matter of four, five or six yards and I was ahead of him by three-and-a-half yards. To this day that is an enigma that I’ll never figure out. It was almost as if I had a tail wind. You can imagine how you feel coming by in a decent time. I never did look at the clock. I knew we were running okay. They had a clock that started with the National Record and went backwards deducting seconds. If there was any time left on the clock, it would tell the audience it was a National Record. I never did look at it until the end.

|

|

| GCR: |

I saw a quote from your coach and Orville said, ‘If Jack hadn’t set that pace, Dale may not have got the record.’ What it reminded me of was when I interviewed Dyrol Burleson and the first time that he broke four minutes in the mile, Ernie Cunliffe of Stanford set a fast pace. Dyrol said, ‘If Ernie hadn’t done that, I don’t think I would have broken four minutes.’ Is there truth to that? Dyrol thought Ernie deserved an assist. Did Jack deserve an assist for setting that fast pace?

|

| DS |

Yes and no. I will say ‘yes’ because, historically, that is how he ran. Historically, I had to work my butt off to even stay close to him. But, when I got better, I could do that. I knew I had a good kick and wondered why his kick wasn’t better. In a flat-out half mile his time was better than mine. He hadn’t beaten me in an 880-yard race, but this guy was quick. Dyrol Burleson liked to outkick people. I, on the other hand, if there wasn’t anybody pushing me and I wanted to get a good time, I would push myself. If Jack wouldn’t have run those quarters, I would have. I knew where we were at with those first two quarters in 62.6. I knew we were in good shape. What I didn’t realize was how much we slacked off in that third quarter. That was a surprise. There is a history to that as, for a lot of runners, you’re race cannot be methodically consistent. There are high points and weak points. Unfortunately, that third lap was a weak point. Since I finished with a fifty-nine, I probably could have come through the third lap in a sixty-four and still had a decent last quarter. I’ll give Jack some credit, but in all those cross country meets I won, I didn’t have anybody set the pace. I did it myself. I was capable of going out and pushing the pace.

|

|

| GCR: |

Speaking of cross country, we haven’t talked about your cross-country racing in high school. Could you provide a few highlights of your high school cross country seasons and championship races?

|

| DS |

I was a mediocre runner and was climbing up the ladder. The Mt. Sac Invitational was huge. My junior year I won my division. My senior year they had one hundred runners in each race, and they had ten races per day. So, there were a thousand racers. That course had run thirteen thousand runners over it. I ran barefoot and it was a hilly course of dirt and gravel. There wasn’t much gravel and was mostly dirt. There was enough gravel that it would deter barefoot running as long as you could tie your shoes. No one ever asked me that question. I didn’t wear shoes because, as I told people, I couldn’t tie them. They thought I was really dumb (laughing). I took control of the race after having a wonderful love affair with the music of Bolero the night before. I set the course record of 8:45. The record had been 9:06 and thirteen thousand runners had been on the course. That was a highlight. When I hit the hills, I powered through them. That was a very momentous experience that builds one’s confidence. And two years after that they moved the course. There were no other spectacular meets. I won a lot of small meets. In the big meets there was more glory and when I stepped out it was subconscious, the more people in the stands, the faster I was going to run.

|

|

| GCR: |

FINAL COMPETITIVE DAYS If we move forward after your amazing 1961-62 year in cross country and track, you never achieved similar results again. Despite the great success, were you yearning even more for well roundedness with your other outdoor activities? Do you look back and wish you had focused for another year more on running and racing, or was the success you had enough, and you were ready for more outdoor activities?

|

| DS |

I was terribly embarrassed by what I was doing at the time. It was a natural progression, like you mentioned. I was also doing more academic work, but that wasn’t a conflict. The running desire wasn’t there as much, and neither was the killer instinct. I was so divided. I was looking forward to going down the river with my shotgun or going duck hunting or just going exploring. I’m embarrassed by that today to a point. But we make the best decisions we can make. When I was reading the book about Bill Bowerman, not all the great athletes came out of their careers at the top, at the zenith performances. Some continued to run, and they didn’t do quite as well. But you have to take the bitter with the sweet.

|

|

| GCR: |

You mentioned earlier how you came close to running a sub-four-minute mile with that best time of 4:03.4 where you were out in 2:59 at the three-quarter mile and made the mistake of starting your kick too early. Is breaking four minutes something that you wish you had on your running resume?

|

| DS |

Absolutely. Absolutely. People will ask me, ‘How fast did you run the mile? What was your best mile time?’ And I would like to say, ‘Three something and not 4:03.’ It’s humiliating. Anyway, that’s okay. I ran a 1:52.6 in high school for 880 yards and ran a 1:52 point something in college one time and I ran forty-nine something for the 440 my first year in junior college. And then I had the strength of a two and three-miler. If you put those two factors together, it was doable though it would have taken more training. I know I could have done it. I was preparing for the two and three-mile, which is a little different than training for the mile. Not a lot, but a little bit.

|

|

| GCR: |

After you finished up your degree and got your teaching certificate, how serious was your effort to train for the 1968 Olympic Trials and do you wish, in retrospect, that you had given it more effort for twelve to eighteen months or was it just too much as you transitioned to teaching and family life?

|

| DS |

I was training with Tracy Smith. I had a family and was thinking about the steeplechase as a good possibility. I was having some good workouts and ran the steeplechase one time. I can’t remember what I ran, but it was decent. But, when I was coming home to my wife, I told her, ‘My heart’s not in this.’ Whether that was a false observation or real, I must believe it was real because I never went back on it. I just hung it up and decided I was not capable of doing that. It’s a bit humiliating. But there were great runners like Steve Prefontaine, who died young, or others who didn’t make it and I thought, ‘I didn’t achieve the accolades some runners had, but I’m still alive and had a good career in academia in high school.’ I’m sort of blessed, though I won’t get religious as I’m not too religious. I do feel like there was somebody watching over me and helping. It would be abrasive to take all the credit myself.

|

|

| GCR: |

COACHING After completing your coursework in Wildlife Management in 1965 and obtaining your teaching certificate, in 1967 you were hired by Wallowa High School, located in remote northeast Oregon, to teach biology and coach track and field. Over a twenty-nine-year high school coaching career, your teams won seven state championships in track and field and two in cross country, and your cross-country teams finished among the top five in the state eight other times. How do you sum up your mentoring hundreds of athletes in the discipline it took to run and compete, add structure to their lives, and overcome adversity and did this have a greater impact on humanity than the great things you did yourself?

|

| DS |

You’re probably right, though they are often not measurable. Periodically, I receive feedback from some of my students. I’ve heard some say that I taught them certain things and that it was a pivotal moment in their life. I thought, ‘Really? Really?’ It was so nice of them to come back and give me that praise or thanks. But that is a slow process that isn’t in front of people. I always did want to produce State champions. I didn’t care about team championships as much when I was coaching in high school. My whole goal was to build individual State champions. And if we had enough champions, then our team would win the State meet. I coached thirty-two State champions. That was one of my goals and the kids were able to achieve that. Hopefully, that carried them forward with a lot of confidence in life. So, I must agree with you that it was a bigger contribution and wasn’t so personal. If I’m out running on a track, I’m not running for anybody but myself, my team, and my school. When you’re coaching kids, it is totally independent, and you are trying to affect their lives in a positive way.

|

|

| GCR: |

Since you had thirty-two State champions and untold other great athletes, it could be difficult to single out a few. But, if you were to name a half dozen of your top athletes from your coaching career for their state championships, times or distances, and leadership, who comes to mind and what can you say about each of them that makes them so memorable?

|

| DS |

That is kind of an easy question to answer. I’m seventy-nine years old now and have been retired for twenty-three years, which is a long time out of the circuit. I am close with nine of my former students. All of them were athletes. And I’m living now in the house of Hans Magnen, who was in high school when I was teaching, and he had both of his parents. He and his wife invited me here to live with them. I’m mobile, so that isn’t an issue. I asked why they were asking me to live with them and Christie, his wife, says, ‘Because we were taught to take care of our mothers and fathers. But they’re dead now and we want to take care of you. I thought, ‘You’re not even blood and you want to take care of me. I don’t need any help now. But I’m going to reach for a Kleenex. I’m going to cry.’ This was unbelievable. When I asked why, she said, ‘Hans said when you were coaching him, you were like a father and you have continued to be so.’ That is what it is all about. Hans has Parkinson’s disease now and is sixty-nine years old, but he is functional. Jeff and Greg Overson are two athletes that stand out. Jeff was the Pac-10 400-meter intermediate hurdles champion around 1974. He was a good runner who was a State Champion in high school in the hurdles, 440-yard dash and short relay. Greg Overson, his brother, was a great javelin thrower who threw around 240 feet. A lot of my students who were very good and came in second or third in the State meet became great professionals in the military. Reed Wynents is a lieutenant colonel and head of the Air Force ROTC at USC. He flew those big C-17 cargo jet planes all over the world. Another one of my athletes, Rory Johnson, was a two-time State 800-meter champion and he is an FBI agent and head of the SWAT team up in Anchorage, Alaska. Mike Kenfield is with OSI, which is the Office of Special Investigation in the Air Force. It is the equivalent to the FBI in the Air Force, and he served in Washington, D.C. I got a chance to give a speech at Andrews Air Force base when he retired after twenty-three years. One athlete is a helicopter pilot. Another, Steve Goss, State 800-meter champion, is Executor of my will. I have four of my students as my beneficiaries. That is how close we are. They are like my kids. Big John Ward taught me this. When I asked him how I could pay him back for all he did for me, he said, ‘You don’t have to do anything, but find some young bucks and help them out.’ It’s a good philosophy and that’s what I tried to do.

|

|

| GCR: |

When you look back at the individuals and teams you coached in cross country or track and field, are there some that overachieved and totally exceeded their expectations or how you thought they could do?

|

| DS |

Reed Wynants was one of them. His dad had been drinking at one of the meets in Corvallis and brushed right across my legs and passed out from drinking vodka all morning. He had a grand mal seizure. I reached down and stuck my finger and pulled his tongue out. He died of alcoholism a short time later. There was alcoholism in his family tree. Reed is forty-seven now and I saw him around last Christmas. I fish with some of the kids in Alaska. They see me as a stable figure. I’m always there for them. It’s like a relay. If you get the baton as the anchor leg and you are in second or third place, you don’t want to let the other three guys down. I’ve always felt that way and they are now raising good kids. I’ve even started some of their kids in an investment program. One of them is only nine years old. I can help. I’m not rich, but I’m doing okay.

|

|

| GCR: |

With your distance runners, did they run year around, every day of the week and what volume of mileage were they running? What type of speed training did you advocate?

|

| DS |

They didn’t train year around for the most part. I rarely had an individual do that – maybe two or three of them. We were a small school with only a hundred and eighty kids at most and some years under a hundred. We had competition for athletes from basketball in the spring. Athletes couldn’t run cross-country in the fall if they were in the football program. Sometimes we competed with baseball. Our training season was relatively short, but many of the athletes came out of basketball or wrestling season and were already in decent shape. All we had to do was fine tune. I didn’t overdo the training. We did a variety of workouts and did repeats on the track. We had a grass track which is very gentle to the legs, though sometimes we had snow on the track. We would run in the hills. On repeats, I believed in quality more than quantity. We would do no more than twelve quarters. There was always a short shag in between. I never let them take more than a two-hundred-meter shag and they had to jog. Sometimes we would cut that down. We would do repeats on the track where the slower kids got a handicap. I’d start them maybe four meters ahead and tell the guy behind that he had three hundred meters or four hundred meters to catch up and get him. I would have kids doing maybe six-hundred-meter repeats and I’d tell one to explode somewhere in the middle. I wouldn’t tell him when to do so, but I told the other athletes that when he moved, they all had to move with him. That way, in a race if a guy tries to move away from the pack, they are already trained for that situation. I tried to take any scenario that might occur in a race and recreate it in training. We did a fair amount of fartlek on the golf course and in the hills, and hill repeats. As we got closer to the season, in order to avoid injuries, I kept them on the grass track or dirt and off the roads. We tried to have a hard day, light day, hard day, light day. We took it medium two days before a race and light the day before a race.

|

|

| GCR: |

What were some of the key factors in your coaching that allowed your athletes to reach their potential and to peak for the big meets, and did you get better at this as the years went by?

|

| DS |

I think a lot of it had to do with the mental aspect of training. I didn’t put a lot of pressure on them. I asked them, ‘What did you learn today that could be useful tomorrow in your race strategy or training?’ They knew we were always pointing to the State meet. We had to qualify to get to State so, technically, we had to be ready for the District meet. The chips were down for the State meet. The lack of pressure from me was good because the kids could create their own desire. And these kids wanted it. They were hungry. If you take any fifteen-or-sixteen-year-old talented and motivated kid, they want to stand on that medal stand and get a medal for winning the State meet. They wanted it and had to have proper training and guidance. I don’t know if I gave them that much guidance except for the emotional and mental side. I did a decent job there. I was taking everything I had learned over the years, all that reading of Artur Lydiard, Percy Cerutty, Emil Zatopek, Bill Bowerman and all the great coaches.

|

|

| GCR: |

WRAP UP You were inducted into the Oregon State Hall of Fame and Santa Ana Junior College HOF. Is it both exciting and humbling to be so honored?

|

| DS |

It is absolutely an ego trip. As I tell my buddies, we can’t get totally away from our ego. At Oregon State there is a big picture of me running that I’ve only seen one or two times. They introduced us at a football game with 35,000 people in the stands at a night game. They called us down on the field and I was wearing a nice, black blazer, and slacks. I thought, ‘Okay, I know how to do this.’ So, I took my shoes off and my socks off and ran down there barefoot. When they introduced me, there were all these athletes on the basketball team who had just been introduced and here I come with bare feet. That got a lot of people laughing. When I was nominated for the Santa Ana Junior College Hall of Fame, I didn’t attend the function, so I sent letter to them that they read during the ceremony and Big John Ward’s granddaughter was in the audience. As an aside, I had been kind of in love with their mother when I was seventeen years old. I went up to Big John’s house for dinner and here was his nineteen-year-old daughter and I thought, ‘Wow! What a dandy!’ She’s the mother of this granddaughter and still alive and beautiful. The granddaughter, Amy, was enamored that I mentioned Big John and invited me to spend some time with her and her husband. What a nice lady. She is a schoolteacher. And this is an extension of what I was talking about earlier and how we can influence other people in life. I had no idea I was ever going to meet his granddaughter.

|

|

| GCR: |

In the fall of 2021 on November 27th, it will be exactly sixty years since your Oregon State teammates and you won the NCAA Cross Country title. Are all five of you still alive and well and is there any thought of a reunion of the team?

|

| DS |

I haven’t heard anything from most of the guys. We don’t know anything about two of the runners, Jerry Brady, and Cliff Thompson. Our third man, Bill Boyd, and I talk every month and I go up to visit him. He is a retired lawyer up in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. Rich Cuddihy, was from Ireland and a bit older than us. We called him the old coot. I have no idea where he is. I have connected with more people in the past few years than all the time before. As a matter of fact, I called up Kenny Moore and just talked to him a week ago and he appreciated the call. He’s out in Hawaii and his voice is difficult to understand as he has a neurological disorder. I’ll try to visit him in Eugene when he is back in Oregon.

|

|

| GCR: |

What is your current health and fitness regimen?

|

| DS |

I can’t run anymore. I had a hip replaced because I had bone on bone. Frankly, everyone asks if I’m still running and I’ll say, ‘How many years do I have to run to satisfy you?’ (laughing). I ran for over fifty years. I get out walking and do some gardening. I had a huge garden when I lived at my previous home. Here I have taken over part of their garden. I do quite a bit of shooting. I’m a gun advocate, not one of these crazy guys. I’m a legal rifle and pistol shooter. I keep up for self defense and am a huge proponent of the Second Amendment. Guns have been my tool all these years. I have a conceal permit and don’t take any chances when I go anywhere. I go for short hikes. I go down to my buddy’s house in Arizona and he goes elk hunting. All I do is help find them and gut them and clean them. Then we hang them up and cut up our meat. Last year we got three elk. The year before we got three. His wife, daughter and he all have a tag so we can get three. They gave me a bunch of meat. I’ve got tons of meat here. I go fishing in Alaska for halibut and salmon up in Yakutat.

|

|

| GCR: |

As a very active man in your late seventies, what are your goals over the next decade and more in outdoorsmanship, activity, family life and other aspects of life?

|

| DS |

Decade? You think I’m going to live that long? (laughing). You are more optimistic than me. I go down to Arizona every November for that elk hunt and we’re going to go down to Lake Powell in September. I go around Sheridan, Montana, which is south of Bozeman. I’ve got a college buddy there and we do some shooting and some travelling around the hills. I love geology and I love ecology, so anywhere I’m out I’m always looking at mountains, rocks, trees, animals. I never get tired of that. I have a very strong appreciation for nature. That is a blessing on my part.

|

|

| GCR: |

When you are asked to sum up in a minute or two the major lessons you have learned during your life from the discipline of running, being a part of the running community, balancing parts of life, teaching and coaching others, and overcoming adversity, what you would like to share with my readers that will help them on the pathway to reaching their potential athletically and as a human being?

|

| DS |

Absolutely never give up. If you give up, success doesn’t happen. When you stay persistent, it happens. I remember when I was hunting with my bow, I would come back and beat myself up because I hadn’t got an elk. Then I would stop and think about how an African lion has huge teeth, big body weight, tremendous claws, is fast and strong and he only makes a kill twenty percent of the time, one out of five times. I’d think, ‘If that is his success rate, why should you expect higher?’ So, never give up. Persistence is key. I was not a very smart person and still am not, but you can still get through life by being persistent and not giving up. Recognize your shortcomings and faults and realize that everyone has shortfalls. But you have strengths and should capitalize on the strengths. Also, try to improve the shortfalls. And the big thing is to always be honest with yourself. There are a lot of people who can’t look themselves in the mirror and analyze why they are taking drugs or have an alcohol problem or something else.

|

|

| |

Inside Stuff |

| Hobbies/Interests |

I love to cook and love different exotic foods. I did some travelling in Europe and wrote down recipes. I liked to cook them. I have a list here I’m looking at of ‘food to make.’ Paella from Spain is one of my favorites. Indian basmati, Masala Murga which is spicy hot chicken, Swedish meatballs, Chinese meatballs, fish stew, barley stew, wontons, spring wrappers, Navaho fried bread and sushi. And I like to cook for other people. Friday I’m going to cook for a friend of mine that is like my daughter. I’m going to cook cheesy halibut that I caught up in Alaska. I cook for Hans here since his wife is down in Arizona visiting a friend. I’ll cook him elk steaks and salmon. The other thing I started doing is investing quite a few years ago and have been keying on helping my granddaughters. I started them out when they were seventeen years old. They are the ones that lost their dad. I had told my son not to worry and that I would take care of the girls. I’ve made a big effort to do so. They will be in good shape in my will. I’m not going to burn up my resources. They are twenty-three years old now. I am hopeful they will be financially secure and don’t have to work at Walmart when they are seventy-five years old

|

| Nicknames |

Occasionally, a handful of people at the University of Oregon called me ‘The Animal.’ I don’t know if it was because I ran barefoot and was strong on hills. If I was called any other names, they were probably socially inappropriate, and I didn’t know about it

|

| Favorite movies |

One that comes to mind is ‘Missouri Breaks’ that was filmed with Jack Nicholson and Marlon Brando. It’s an outdoor movie filmed up on the Big Sandy River in Montana. It is a fantastic movie. The scenery is gorgeous, and the acting is superb. ‘Cape Fear’ is another one I like. One that really got me is ‘Lonely are the Brave’ with Kirk Douglas and Walter Matthau. I don’t have a television here now but, in the past, I watched a lot of documentaries. When I’m watching a movie, I’m critical because I’ll see a telephone pole that shouldn’t be there or the wrong vegetation and know that’s not right and they are depicting the wrong thing. That’s terrible, so I have to keep my mouth shut when I’m watching movies

|

| Favorite TV shows |

I didn’t watch a lot of TV when I was young. I was usually out roaming around. As I got older, I watched documentaries and nature shows

|

| Favorite music |

Classical music by a longshot. Tchaikovsky, Wagner, Maurice Ravel’s ‘Bolero,’ Edward Greig, Bedrich Smetana. Tchaikovsky is probably my favorite

|

| Favorite books |

I do a lot of reading and am currently reading, for the third time, ‘James Cook,’ about Captain Cook who sailed around the world. My big favorite is ‘The Northwest Egg.’ I love the wilderness and, unfortunately, every time somebody pioneers into the wilderness, they break the ice and then my wilderness has a downhill go. Louis and Clark came through and started surveying and look what we’ve got today – cities and roads. I do take my hat off to Louis and Clark and I have read a lot about Alexander McKenzie who beat Lewis and Clark to the Pacific Ocean in 1793. But he came overland in Canada several hundred miles north. Thomas Jefferson had Alexander McKenzie’s journals in his library, and he gave a copy to Lewis and Clark. So, when they came across, they knew approximately their latitude the whole time. McKenzie was very good with his astrological calculations. I’ve read David Thompson, the great explorer who mapped the entire Columbia River. I try to camp where they did so I can get a feel for where they were living. This keeps my mind moving in the area of getting exercise. I had a hard time in English class because I didn’t like to read fiction books. If it didn’t happen, I didn’t want to read about it. That’s why I didn’t get very good grades in English. My teachers would tell me I had to read something, and I would say, ‘It didn’t happen. I don’t want to read it’

|

| First cars |

I had a Chevy pickup truck and, later, a Toyota pickup truck when they were more popular. I had a lot of firewood to haul

|

| Current car |

I’ve got a Toyota Camry now. It gets fantastic mileage, forty-eight miles a gallon at my zenith, at the maximum

|

| First Jobs |

I got a job working as a box boy in a store. I’d only been in the job for about a week or week-and-a-half and here comes two guys in a Cadillac. They get out and are union boys. I was wondering, ‘Why does it take two and not one?’ I didn’t trust these guys and was thinking, ‘What is a union going to do for me?’ I remember taking off my apron in the parking lot and walking off. I didn’t take a lot of crap. I was a little guy and was probably suffering from the ‘Little Man Complex.’ But I was smart enough to know that if I gave them eight or ten dollars a month, what was I going to get out of that? And I wasn’t exactly sure of that. Another time I had a job washing dishes in a snack shop and bussing tables. The boss would have me come out fifteen minutes before my starting time because they were busy, and I never got paid for that. Then it was thirty minutes early and next forty-five minutes early. Finally, one time I waited until they got in a full rush of customers, took my apron off, and walked out. I didn’t take a lot of crap. I wasn’t trying to be a bad guy. I was responding to people who were treating me unfairly

|

| Family |