|

|

|

garycohenrunning.com

garycohenrunning.com

be healthy • get more fit • race faster

| |

|

"All in a Day’s Run" is for competitive runners,

fitness enthusiasts and anyone who needs a "spark" to get healthier by increasing exercise and eating more nutritionally.

Click here for more info or to order

This is what the running elite has to say about "All in a Day's Run":

"Gary's experiences and thoughts are very entertaining, all levels of

runners can relate to them."

Brian Sell — 2008 U.S. Olympic Marathoner

"Each of Gary's essays is a short read with great information on training,

racing and nutrition."

Dave McGillivray — Boston Marathon Race Director

|

|

|

|

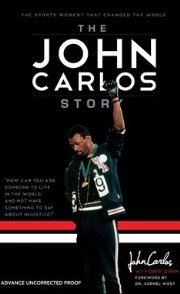

Dr. John W. Carlos is the 1968 Olympic Bronze Medalist at 200 meters, but is remembered more for the human rights statement made with his fellow Olympic medalists during the subsequent medal ceremony. John was influenced by social injustices in his youth and conversations with both Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. which forged his life as one that stands for human rights and seeks to curb social injustices. Carlos was a founding member of the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR). He set a World Record of 19.92 seconds for 200 meters at the 1968 Olympic Trials. In 1967 John ran for East Texas State and was a four-time Lone Star Conference champion, helping the Lions to the 1967 LSC title. He was Gold Medalist at 200 meters at the 1967 Pan American Games in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada and set indoor world bests in the 60-yard dash (5.9) and the indoor 220-yard dash (21.2). At the 1969 NCAA Track and Field Championships John won the 100 and 220 yard dashes, anchored San Jose State to the 4 x 110 yard relay title and led Spartans to the NCAA team championship. That same year Carlos won all 14 of his 200m/220y races and 17 of 18 100m/100y races. In 1970 John won 11 of 11 100m/100y races and 10 of 10 200m/220y races until injured at AAUs. He then tried football to support his family before injuring a knee. John represented Puma at the 1972 Olympics and was involved with the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics Organizing Committee. For much of his adult life he has been a guidance counselor and track coach. He is the co-author of ‘The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World.’ John was inducted into the USA Track and Field Hall of Fame (2003), National Consortium for Academics and Sports HOF (2010), Texas A and M-Commerce (East Texas State) HOF (2012) and San Jose Sports HOF (2015). His personal best times are: 60 yards – 5.9; 100 yards – 9.1; 100 meters – 10.0; 200 meters – 19.92 and 440 yards – 47.0. John graduated from San Jose State and was awarded honorary doctorates from California State (2008), Texas A and M University-Commerce (formerly East Texas State) (2012) and San Jose State (2012). He was gracious to spend over two hours on the phone on February 1, 2018 for this interview.

|

|

| GCR: |

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the 1968 Olympics and that wonderful statement Tommie Smith and you made for human rights during the medal ceremony for the 200 meters. Here is a big question – how were these few minutes the culmination of your life to that point and how did that gesture change and define your life afterward for the next fifty years?

|

| AA |

That wasn’t the defining point in my life as far my whole life, but it was one step in my life that took place in Mexico City. But I think it did detail the rest of my life from that point on in terms of it being such a public spectacle. Any time I got involved in situations such as that they were always on a more personal and private level in my community. But this was so public that it just changed my life. People had an opportunity to have a thought about what they observed and it took people fifty years to reason and to have some understanding and clarification as to what they viewed fifty years ago.

|

|

| GCR: |

I was ten or maybe just eleven years old at the time, but now when I read and watch programs about 1968, just as that moment was a defining line in your life, how parallel is it that the year of 1968 with the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the Vietnam War protests and President Johnson declining to seek re-election, North Korea capturing the USS Pueblo, the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, riots in the streets of many cities and at the Democratic National Convention, and more is a defining time in United States history?

|

| AA |

My thoughts relative to time is that I think everything was premeditated – the assassinations, the KKK, demonstrations against the KKK, the civil rights movement. All this is mathematically in the stars. All we could do was wish for our generation to do what is right for society and let the cards fall where they may in time. We couldn’t just sit back and see atrocities take place and see so many people have hatred toward one another. People didn’t even know why or who they had hatred for. We couldn’t just sit there with our hands in our pockets and let this dolly go back and forth. We had to step up to the plate and say, ‘enough’s enough.’

|

|

| GCR: |

It’s interesting too how the realm of sports has put the onus on social issues and helped with forward movement. Along with Jackie Robinson’s stepping forward to desegregate Major League Baseball and Muhammad Ali’s refusing to step forward to serve in the army, the gesture by Tommie Smith and you, are arguably the three most defining events in the social and political history of sports in the United States. What are your thoughts on how sports figures even to this day are helping to advance social issues in the United States?

|

| JC |

Far beyond Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali and me, we can go all of the way back to Jack Johnson. Individuals in that era took it upon themselves to make statements about race relations. Jack Johnson had to deal with on a daily basis that he was Heavyweight Boxing Champ of the world and the fact that he had a white wife. He couldn’t take her across some borders. People thought he had kidnapped her as black men weren’t supposed to have an association with another ethnic group. And Carl Robeson made quite a few statements. Then Jackie Robinson came in. There are a lot of people who make statements that make a move, but many are on the private side of the door. People such as Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali and me did ours in public. But many people had an opportunity to do things that weren’t public. We did what we did, it was in the headlines and some people thought it was a good thing and others thought it was a bad thing. We put it out there so that people in time, when the dust settled, could come to the conclusion as to whether we did the right thing or the wrong thing. It wasn’t like someone could dictate what we are and then have the public just eat it up.

|

|

| GCR: |

In your autobiography, ‘The John Carlos Story,’ you profess ‘I still feel the fire. I didn’t like the way the world was, and I believe there needs to be some changes about the way the world is.’ If we look at the goals of social justice, racial equality and fairness to all without bias toward race, gender, religion or other characteristics and we as a people are on a football field going toward that goal line of where things need to be, how many yards away were we in 1968 and how many yards are there still to go in 2018?

|

| AA |

We’ve still got a whole field to go. Especially when you sit back and think of President number forty-five being in office and the rhetoric he’s been putting out there. Look at the division he’s been spreading out there across this country, across the United States. Just think about what he’s done and the KKK taking their sheets off to let people know what they think. And there are individuals at a campaign rally that see a black man walk up the aisle and they laugh at him because he is trying to express himself. Then we see an individual taking a knee because he is concerned about the deaths of blacks in particular being harassed or killed by law enforcement. They want to take away these people’s first amendment rights. The President is co-signing that which has brought out a lot of anger, a lot of hatred and a lot of division in this country. When we sit back and think how far we have come and how far we have to go, we’re still at ground zero.

|

|

| GCR: |

That is important to hear from you because I wanted to get your opinion; I value your opinion and thank you. In the past couple of years Colin Kaepernick started what became repeated gestures in protest of wrongdoings against minorities and shootings of unarmed blacks that have most visibly manifested in the refusal to stand for the National Anthem before football games. What are your thoughts on this recent series of demonstrations for human rights that are bringing these injustices to the public in what may be an uncomfortable way, but a necessary way?

|

| AA |

The best way I can describe it is to use an analogy back to when we were kids. Do you recall when you were a youngster and were sick and your mother would get that big spoon and you would be running from her because she was going to make you take that castor oil? You did not like it, but then later your dad would pull you aside and say, ‘Son, do you remember when you were going to parties and all of your friends were home sick, but you were at the parties with all the girls? Did it ever dawn on you why you weren’t sick and you made it to the parties?’ ‘No, dad, why?’ ‘Son, it’s because of that castor oil. It didn’t have to taste good or feel good to be good for you.’ And that is exactly how any demonstrators are. We are that castor oil. You don’t like it. You don’t like the taste. You don’t like the feel. But, in the long run you will find it was good for you.

|

|

| GCR: |

When people look at poverty and other societal issues, they tend to focus on black neighborhoods when poverty and social justice doesn’t know color. Another compelling statement you made in your book is ‘without education, housing and employment we were going from familyhood to neighborhood to just the hood.’ How much are guns, drugs, disintegrating families, lack of mentors, scarce employment and housing options and dependence on the government affecting not just inner city poor and black citizens, but also rural and white people who are living in poverty in modern days, who are all in this together and who all need our help?

|

| AA |

When you sit back and think about it, there are so many things that are intertwined – race relations, homelessness, poverty and they are all wrapped up together. Then we can go back a little deeper and think how many airplanes did the poor blacks have or how many airplanes did the poor whites have to bring drugs into their community? Someone that had the power brought them in. There is no way you can tell me that you can take a spaceship and go to the moon and land a half mile from where you wanted to land, but you can’t stop drugs from coming into the hood? Or you can’t stop rats and disease from being in the hood? There are drugs in the hood that are in the rich communities. There is division and somebody is orchestrating it. When I grew up as a kid I remember seeing the difference in my neighborhood and a white neighborhood. In the white neighborhood there were cafes, restaurants and grocery stores. There was everything the people needed. In my neighborhood in Harlem I could go up and down the street and walk in my neighborhood and there were three bars on one block and two liquor stores. They were advertising Schlitz Malt Liquor and E and J Brandy. The problems were there and on the less fortunate. There are problems that should be on the table with the Congress and the Senate. We should be saying to the Board of Education, ‘You’ve got to do a better job.’ And to law enforcement, ‘You’ve got to do a better job.’ But the bottom line is that they are concerned about their own personal agendas and those individuals that we just talked about are upside down. Then at the same time they sprinkle race relations in there. Poor whites don’t understand that blacks are suffering financially and economically as much as they are. And on the other side poor blacks don’t realize that poor whites are that way. They’re in the same pot. Poor Hispanics are in the same pot relative to not having something. And those in the Fortune 500 and the fats cats are the ones who walk over everyone. It’s like taking two cockroaches and putting them in a pickle jar with a big crumb of bread and they are enjoying life – they’ve got food, they’ve got love. Then you put a piece of cardboard between them with a crumb on each side. And then some day you stop dropping the crumb. Then you pull that divider out and the next time you drop the crumb in there somebody is going to die. And that is the situation you see people in today in enclosed neighborhoods. It is worse than sad. It is tragic.

|

|

| GCR: |

These are some great comments and analogies regarding social justice. Now let’s go back in more detail to the events of 1968. First, there was real discussion of an Olympic boycott by black athletes and you said, ‘By going you represent yourself. By boycotting you are with everyone.’ Could you discuss the tough choice you and others faced of sacrificing the Olympic opportunity after five or ten years of training for the chance to make a bigger difference in the world? How tough of a situation was that for the athletes?

|

| AA |

It was tremendously tough for the athletes to even consider giving up their dreams they had as a child to go to the Olympic Games. No one had ever approached them with these thoughts before. They were in the heat of passion of making this team. They were training every day. There was the talk of the Olympics in the news and they were so close. Then two years before the Games the Olympic Project for Human Rights came along and said that we needed to come together to boycott the Olympic Games. That’s a tremendous sacrifice. We couldn’t tell them, ‘You have to boycott these Olympic Games.’ All we could do is put all of the data on the table and let them decide for themselves if it was worth it for them to boycott the Olympic Games. A lot of those individuals didn’t understand at that particular time that this boycott wasn’t for them. This boycott was for their kids, and for their kids’ kids. It was to make this a better world and to make people have some clarity as to why these individuals would sacrifice going to the Olympic Games to represent the United States. Maybe by boycotting then people would come to the table to understand why they boycotted. It’s the same as the guy who took a knee. They need to know why he took a knee.

|

|

| GCR: |

As an addition to the previous thoughts, when you talked with Dr. King and asked him why he was going back to Memphis during the 1968 sanitation strike even though he had received death threats, he said, ‘I have to go back and stand for those that won’t stand for themselves, and I have to go back for those who can’t stand for themselves.’ What impact did this have on you, and did it really set the stage for what Tommie and you did in Mexico City?

|

| AA |

When he set that it gave me a reference point as to who I am and what I have been doing all of my life. I never had a phrase I could use until he made that statement. I had stood for those who couldn’t stand for themselves and who wouldn’t stand for themselves in the schools and when law enforcement came along and told us to move. I told them, ‘We don’t have to move. We live here.’ When we think about change, when we talk about Mr. Kaepernick, he is concerned about the deaths of certain individuals throughout our history. He has a grave concern about who is being prosecuted for the crimes that are being committed. You can take a slide rule and figure out from day one to the current day how many law enforcement officers went to jail. All they have to say is, ‘I was in fear for my life.’ If someone came up to me and I shot him down and I said, ‘I had fear for my life,’ do you think that they would let me walk? That’s the part of the law that people aren’t listening to. It’s not that they need to make new laws. They need to get the Supreme Court off of their butts to tell law enforcement to uphold the laws we have. We need to weed out the crooked police and not just protect the shield. We can’t just put it all on law enforcement and say that they are bad. Law enforcement is not bad, but they have rogues. There are rouges that work in the hospitals. There are rogues that work in the post office. There are rogues that work at the Board of Education. But the difference is that the law enforcement rogues carry a gun, ammunition and a badge.

|

|

| GCR: |

That is a detriment to law enforcement because they make a bad statement for the vast majority of police officers because there are plenty of white officers who serve in black communities, that die serving black citizens and then these rogue officers make a bad name for everybody.

|

| AA |

That’s right. But it’s like this – if I have cancer in my fingers, should I allow my fingers to remain with my body? Or do I remove the fingers to try and save my body. And so often they choose to close their eyes rather than doing something in-house to weed these rogue cops out. But these rogue cops’ actions are being dismissed. That’s all Mr. Kaepernick is saying. Any decent person would say that. What if white police went to white neighborhoods and started gunning people down to the extent they are doing it in the black neighborhoods? Do you think the white folks would tolerate that? They would not. But we don’t have any means for justice other than what we make by me putting my fist in the sky in a non-violent act. The justice that we made by marching in Selma was a non-violent act by those individuals that were marching.

|

|

| GCR: |

Let’s focus for a few minutes on your Olympic final and the aftermath on the podium. I’ve watched that 200 meter final repeatedly, read your thoughts about the actual race and how you had told Coach Bud Winters you weren’t going to test Tommie Smith for the Gold and, when I watch, it does not appear that you raced all-out to win after coming off of the turn with a big lead. Will you describe the race, your start, your effort and what went through your mind and body for those twenty seconds?

|

| AA |

First, let me tell you that I came out of New York and from the time that I was a kid running in high school I had a lot of problems in my mind that set off races. In this particular race I was undecided if I was going to run this race to win this race. The reason more so was the fact that I wanted to make a statement and Mr. Smith said he that was with me on that. In my mind I said, ‘The race is his. He can have the race.’ I had to go back and call around to some of the fellows to tell them not to make any bets because I was undecided what I was going to do.’ Since Tommie said he was down with me to make some sort a statement, then the race was his because he admired medals and trophies and I’m not into that. Just the memories of me being there with the fellows and having a good time and having a good competition, I can live with that. The tokens that they give, I used to give to the girls when I was in high school. The medal that they gave me from the Olympics – I don’t know where that medal is today. I told my father that I didn’t know what I was going to do in the race. I wanted to set a precedent that once I made up my mind that I was going to give the race up to let them know that if I wanted it, I could have it. Before the race I had eyes down the track at Mr. Smith and Mr. Edwards. They wanted to talk some trash like it was me running, but I said that you will see me before it settles. Tommie came up like he had a groin muscle pull and I knew it was fake. I trained with the dude every day. But I knew he wanted that medal more than anything. I ran that first 110 and when I came off the turn you could see me actually pull back. When I turned around to tell him to stop bulls**tting and to come on, then he came flying by me. I had eyes down the track and I didn’t even think about Peter Norman until the last yards of the race. You can see in the video me turn from my left all the way to my right. The best part of Peter’s race is always his last twenty meters. When I looked up at the clock results, I think I was happier for Peter Norman than I was for Tommie or myself. Here’s a white guy who ran twenty flat for 200 meters. That was unheard of. That was a record in and of itself.

|

|

| GCR: |

How surprising and important was it to have the support of Peter Norman, the Australian who earned the Silver Medal, in your stand for human rights and how did he positively affect you that day and for the rest of your life?

|

| AA |

First, a person had to have the right temperament to be involved in that type of situation. The average white guy wouldn’t have had the understanding of the problems we had. The things that black people were up against in the United States, he saw happening to aborigine people in Australia. If you think about that place and time, Australia was parallel to South Africa. So, he was a tremendous asset and let me tell you about his sensitivity to that particular demonstration. When you think about Peter Norman, for the better part of 43 years here in the United States, they didn’t even discuss Peter Norman. Most times when they showed the picture, they tried to take Peter Norman out of the picture. So I thought back in time to when John Brown supported Frederick Douglas. Everything that John Brown did, they tried to erase out of history. Then with everything that Peter Norman did, they also tried to erase. And now with the modern day black athletes, the football players that took a knee, there are white athletes that took a knee with them or put their hands on their shoulders to lend support to them. And they have been white-washed like they never existed.

|

|

| GCR: |

That is true as it seems like there is white support for a lot of civil rights. As an aside, I grew up as a white distance runner on a mostly black high school track team in Miami, Florida and, John, when I went to the Florida state meet my senior year there were eight of us and I was the only white guy. There were four of us to a room and two to a bed and, while we saw color, we didn’t focus on it or have negative thoughts as we were all brothers.

|

| AA |

That’s right as first of all we are a team. But what the media dispenses to the general public and what are the headlines in the paper does is that they erase these guys because they don’t want the white society to realize that there are white athletes who are also saying, ‘I’m somebody and I can stand up for justice and equality.’ If the public doesn’t see these guys and the media doesn’t mention these guys, then it seems like black versus whites. That’s why the media never exposed who John Brown was. That’s why they never exposed who Peter Norman was. That’s why they never expose who these professional football players are. The media doesn’t want the public to know that white people can cross the line and be righteous about equality and justice for society in general.

|

|

| GCR: |

Those are some profound thoughts. But let’s go back again to 1968 and your statement on the medal podium. What were the thoughts in your head when you received your medal, on the podium while the anthem playing, and in the immediate aftermath?

|

| AA |

I was excited before the race. It was time to get this thing on. That was what I came here for. I didn’t come to win a Gold Medal. I came to win ‘a’ medal so that I could do what I needed to do on the medal stand. Once I got on the victory stand, some things hit me real strong. The first thing was the vision I had when I was a little kid. God gave me a vision of me being in a stadium or forum with a whole bunch of people and me standing on a box. He didn’t show me anything except me on this box and they were applauding. It was exciting that they were applauding for me because I was only seven or eight years old when I got this vision. I’m right-handed, but in the vision I raised my left hand. When you are a kid when you see someone you know you are going to wave at them and raise your hand high up. But just as you see that picture in 1968 when my arm froze in time in that vision it was like it hit a switch and all of the glory and cheers turned to anger and boos. They started cussing and spitting and telling me where to go and name-calling - the whole nine yards. It shook me up so badly that later on that evening when we went out to dinner I told my daddy before we went out to the movies and I explained to him what I had seen and he brought me to his chest and he said, ‘There isn’t anybody who’s going to bother you like that. I’m going to protect you and house you and get you a good education and nobody is going to bother you like that.’ But at the dinner table my mom said, ‘it looks like God may have something special for this kid. We’re going to have to wait and see what it is.’ So when I was on that victory stand, the exact same thing that happened to me as a kid in that vision happened that day on that victory stand. The second thing I thought of was those stories my father had told me about when he was in the First World War, how the white officers treated the black soldiers and how they were perceived when they came back from the war. All of this ran through my mind. There was the hatred that was in the stands when we put our fists up to the sky. I thought about why it was necessary for me to put my fist up to the sky. It was the same hatred that was being shown to me in that vision I had. So, that’s what was running through my mind while we were in that winner’s circle.

|

|

| GCR: |

How ironic is it that the only reason the black gloves were there was because Tommie Smith had asked his wife to bring a pair of gloves so that he wouldn’t have to touch skin if he shook the hand of IOC head, Avery Brundage?

|

| AA |

Well, that’s what he said they were for. He just told me that he had gloves and I said to bring them with us.

|

|

| GCR: |

How divisive a figure was Avery Brundage going all the way back to his support of the 1936 Olympics in an anti-Semitic Germany led by Adolph Hitler when there was a strong sentiment for the U.S. to boycott those Games and then forward to his conflict-ridden policies in the 1960s? Wasn’t he in many ways a poisonous person heading that organization?

|

| AA |

When Avery Brundage was there in the 1960s he was an old man. So Avery Brundage may have been the forefront while there were others behind him who kept pushing him. How could people allow an individual such as that to head the organization that was biased toward so many individuals? To many people Avery Brundage was like a saint. There were lots of people at the time who couldn’t belong to this club or that club and they didn’t want to see certain people come into these clubs. And then he referred to us as boys in 1968. That was kind of like plantation talk to me.

|

|

| GCR: |

Let’s go back to your youth in Harlem. John, you talked a bit about your dad who was a World War I veteran and a hard-working cobbler with his own business while your mom was a nurse. What are the main characteristics within you today from each of your parents?

|

| AA |

Everything you see in me comes from my parents from day one. My father was a shoe-maker and then he was a hustler on the side. He was a gambler, not so much because he liked gambling, but because he liked supporting his family. Anything he was good at he would do to try and make a better life for his family. My mom and dad got married when they were young and started a family. My mom and her sister used to go to the abortion offices in Harlem and clean up the doctors’ offices. That’s how my mother went back to school and became a nurse’s aide. I told her, ‘Momma, you can go to school and you can be a doctor.’ So one day she listened to me and she took it up and went back to school. All the values and morals and respect and honor that I have in me, you can rest assured that my mother and father drove that into me and my brother and sister.

|

|

| GCR: |

Track and field wasn’t your first sport as a youth. For those aren’t familiar with your story, could you tell us briefly how you became interested in the Olympics and swimming and then the disappointment of why didn’t stay in the sport of swimming?

|

| AA |

When I was a kid I was the best male swimmer in Harlem. And we were swimming in the Harlem River and in the Hudson River. Back then radio was like TV is now. One day I happened to hear on the radio about this woman who was going to swim the English Channel. The key word is ‘swim.’ So I asked my dad and said, ‘Pops, what’s the English Channel and why is this woman going to swim it?’ He said, ‘Son, I swim like a rock straight to the bottom. But I’ll find out everything and explain it to you.’ I said ‘Daddy, if she swims the English Channel, does she have to swim at night?’ And he looked surprised. Then I asked him, ‘How does she go to the bathroom when she has to go?’ He said ‘I’ll find out. And why do you want to know if she swims at night?’ I said, ‘I want to know that if there are sharks in the water.’ So, he went to find out. And then along that time period I heard talk about the Olympic Games and asked him’ ‘What are the Olympic Games?’ And he told me, ‘that is when all the countries, all the nations of the world come together to explore who is the strongest mentally and who is the strongest physically to represent their country.’ Right away I said, ‘Daddy, do they have any black Olympic swimmers in America?’ And he said, ‘No.’ I said, ‘I’m going to be the first black to represent America in swimming.’ I worked on that for pretty much two years, at least a year and a half. Then my father looked at me and said, ‘Son,’ and I could see in his face that it wasn’t going to be a good talk. It was like he was hurting in his face. He said, ‘Son, I know you want to go to the Olympics as a swimmer, but that’s never going to happen. I looked at him and said, ‘Pop, what do you mean. I’m the best swimmer in the city.’ He said, ‘Son, you and your friends leave our home and we go from Colonial Pool up to Highbridge Pool in the white area. What happens when you all go in the pool?’ I had noticed that as soon as we jumped in the pool the white parents would jump up and call their kids to get out of the water right away. It reminded me of the story of black actress Dorothy Dandridge who they say got in a pool at a Las Vegas hotel in the 1950s and afterward the hotel staff drained the whole pool. Harry Belafonte said when he was a young entertainer coming up they told him there were some things as a black man that you don’t do. You don’t eat in these restaurants and you definitely don’t go to the pool and get in the water. So, when my dad told me this and I got to thinking about how the parents got up and called their kids out of the water, it just reinforced in my mind that we had a really serious problem and I didn’t see a whole bunch of people trying to challenge the system about these problems. Once again I had the desire to make the change.

|

|

| GCR: |

Then you tried to take up boxing and since your mom was worried about you getting hurt you finally took up running. Could you tell us how this happened?

|

| AA |

In boxing I was good. I had a coach who first off told me I had to get a mouthpiece and jock and cup and boxing shoes. I didn’t have money and I was never going to go to my parents to ask for these things. So my coach paid for all of this stuff. He was training me and he told me that I was good enough to go pro. But I had to get my mom and dad’s consent to even go semi-professional with this coach. I went to my father and he said, ‘Son, if that’s what you want to do, it’s okay with me. But you’ve got to get the blessing of your mother.’ When I went to my mom she explained to me as best as she could that I was her youngest son, boxing is a brutal game and she didn’t want me to get involved in that.’ I was trying to explain to my mother and I said, ‘Mom, all I want to do is make a million dollars. If I make a million dollars they will have to find a hundred and ten million dollars to get me back in the ring.’ But she made me promise that I wouldn’t box. You know how when you are a kid and you want to do something so bad and your parents say that you can’t and your chest is sticking out and you can hardly breathe? That’s the way I felt on that particular day. It was like the day my father told me I wouldn’t be able to go to the Olympics as a swimmer.

|

|

| GCR: |

Thankfully, clouds can have a silver lining. So could you tell us a bit about the needy in Harlem, your admiration of Robin Hood and how this got you running, but not necessarily in track and field?

|

| AA |

The police got wind that there were some break-ins at the freight yards. My hero on TV was a guy named Robin Hood. I was impressed because he wasn’t concerned about the laws of the Sheriff of Nottingham. He was concerned about God’s rules. There were bad drugs in our neighborhood and there was one called ‘King Kong.’ There were many men using it who weren’t fathers to their kids and weren’t the man of the house to their wives. They couldn’t buy a birthday present for their daughter or a pair of tennis shoes for their son. Without shoes he was going to fail P.E. class. He was losing respect from his wife because she thought he didn’t want any type of job. And then someone comes up like Billie Holiday in that movie, ‘Lady Sings the Blues,’ and says take this package to help you forget. The guy goes to Europe and then one day looks in the mirror and says, ‘I don’t like that guy.’ How can you not like yourself? And they give him this package and say it’s a weekend trip. He doesn’t know it’s going to get him for a lifetime. With so many black fathers missing in action I saw families with four kids trying to survive with hand-me-down clothes. Social Services wouldn’t even say good morning to people when they went to their homes. They were looking under their beds. They were looking in their closets. They were looking in their ashtrays. They were looking for one thing only – anything that would exemplify that there was a man in the house. They were looking under the bed for his shoes or in the closet for his trousers or in the ashtray for his cigar. If they found it then their sustenance was cut off. I was looking at that and how I could help. I thought of Robin Hood and the tariffs coming through Nottingham Forest. All of them freight trains were coming in with all sorts of goods that could help people that weren’t able. So, I started hitting the freight trains. My two buddies and I started hitting the trains.

|

|

| GCR: |

Wasn’t this about the time as you relate in your book that two law enforcement officers helped get you on the pathway toward officially running in races rather than on the streets?

|

| AA |

Yes, there were these two detectives, Mr. Lutz and Mr. Brown, that knew my father real well because they gambled together and so forth. Mr. Lutz was about five feet eleven inches and Mr. Brown was about six feet six. They went over to my father and told them he needed to talk to me but my father told them it was their job. They told him I was over at McCombs Park where they built the new Yankee Stadium. They came over there and had the black and green cars that blocked the whole park off. They came in and found me and had me sit up against the fence. Then they stood me up on the infield on the turn and Mr. Lutz said, ‘John, there’s been some break-ins and we think we know who has been doing them. But, we can’t issue anything until we catch them.’ Then he pushed his nose up against mine and said, ‘And we’re going to catch him.’ They were leaving me a message. Then Mr. Brown said, ‘Go ahead and tell John the other thing.’ So, Mr. Lutz said, ‘You have a talent. You’re a runner.’ When they said that I sort of shrunk back and then Mr. Brown slapped me right upside of my head. If he didn’t get me on one side he got me on the other side of my head. Then he told me not to disrespect Mr. Lutz. They then said there was a lot of purse snatching going on in the neighborhood. When they said I was a runner it made me think of my mom when she was working at the hospital. She was also working at night to try to bring some more money into the house. She went out one night to work for some people and came home twenty-five or thirty minutes later. Her legs were bleeding and her clothes were torn up. Somebody had snatched her purse. My brother and I were going to look for him. But my mother said, ‘I got my purse back.’ We asked, ‘How did you get your purse back?’ She said, ‘I ran him down.’ So I thought of this and said to Mr. Brown, ‘Everybody runs. It’s not special.’ But he said, ‘no - you’re special.’ He gave me a phone number to call of Mr. Joey Hansen with the New York 5A Club and that’s how my career got started in track. Since my father was a shoemaker he would make us a pair of cordovans. Those shoes would last for ten years. We didn’t have sneakers. When we went to the P.A.L indoor track meets the guy there had old Converse shoes because he would buy used shoes.

|

|

| GCR: |

We often learn from our coaches some characteristics that we wish to follow and other traits we wish to avoid. What did you learn from your coach, Mr. Youngerman? And do you have some early racing memories?

|

| AA |

Mr. Youngerman wasn’t really a coach. He was just there to give us spikes. He didn’t know anything about track. In that era there were a lot of guys who didn’t know about coaching. What I’m trying to say is that Mr. Youngerman wasn’t the only one. A lot of guys didn’t know about coaching, but it was a job where they could pick up a little extra stipend. I remember early on when we were getting to ready to run the mile relay. Guys were sitting on the floor and watching the older guys run. We were novices and we were watching the open runners run in their heats. My guys were saying how those guys were fast and there was no way we could beat them. I said, ‘They look fast because we are sitting on the floor watching.’ And the fans in the Armory were singing songs about the different schools. They would sing for Boys high, Bradford and all of them. No one had a song about M, M and T. But we went out and in our race we broke the novice record. Then we had lunch and when we came back later that afternoon there was a song about M, M and T. I said, ‘Now you see. Now we have a reputation.’ Then we came back and broke the record that we had set earlier that day.

|

|

| GCR: |

So that was your introduction to organized running?

|

| AA |

I started running track because those police told me to run around this one track until they stopped me. Then they forgot about me. I must have run around the track fifty times that day. At the Pioneer Club, when they asked me what event I ran, I told them I was a distance runner. So there were some older guys who were running 660s. I didn’t know what a 660 was, but I was watching them run and they ran five of them while I was talking to the coach. Incidentally, when I went down there I had no track shoes. I had my cordovans on, and some 7-Eleven jersey and my duffel coat. He said, ‘Where is your gear, your training outfit?’ I said, ‘this is it coach. I don’t have a training outfit.’ He told me that they were running 660s and I needed to run with them. I ran the 660s on the wooden floors. On the straightaway I was running like crazy, but when it came to the turn, I was sliding on the turn. And I was slanting my head the same way to keep from running into the wall. When I was down the straightaway I was way out in the lead and then on the turn I was way up into the wall. The guys would pass me up until I hit the straightaway on the other side and I would run them down again. I ran three of them and that treated me alright. But on the fourth one I went to run and I passed out. I never experienced anything of that sort and they said I fell like a piano out of the window. I remember the guys taking me out after practice and I was still kind of drowsy. It was snowing and cold outside. One of the older guys said, ‘Who the heck does that kid think he is?’ I wanted to say something, but before I could open my mouth, one of the other older guys said, ‘I don’t know who that kid is, but I think pretty soon everyone is going to know who he is.’ That was just another attitude. I think the thing that really connected me and made me fall in love with track was when I felt that I was going to get something out of it.

|

|

| GCR: |

After accidentally becoming a track and field athlete, it must have been surprising in the pathway you were on?

|

| AA |

And what I got out of it was I got a chance to see the world. The first place I went to was Trinidad. I saw a country that had a black President, black nurses, black doctors, black bus drivers - it was just a black oriented country. I was so impressed with it. I thought, ‘All I have to do is do my exercises, touch me toes, do my jumping jacks and I can come here every year?’ I was worried about whether I would make the team, but now I had something to shoot for. After I went there one year Olan Cassell told me I was going to Europe. ‘I don’t want to go to Europe. I want to go back to Trinidad.’ But he told me that I needed to go. I had just gravitated to the sport and I got a chance to see the world.

|

|

| GCR: |

We talked at length earlier about your gesture in Mexico City, but you did some earlier protesting of unfair treatment and policies as a teenager. Could you tell us a bit about how seeing unfairness as a teenager really got you going versus what people saw in 1968 and how you were protesting unfair things for quite a while?

|

| AA |

It wasn’t even when I was a teenager. I was less than a teenager. When I was a young kid I saw one thing on Lennox Avenue that really blew me away. It was early one morning on the weekend. There were two winos or what we would call transients today. But back then they were just winos. One was black and one was white and they were both lying in the island in the middle of Lennox Avenue. It’s probably still there today. And both of them were sleeping. There was a young white cop who went over to the white guy who was laying there and he took his night stick out. The guy was just lying on the ground without moving so he went down toward the ground and poked his night stick in his chest. The guy woke up and he told him to go on. The black guy was lying maybe eight yards or ten yards away. The cop went down to this guy and I was expecting him to poke him in the chest. But he went to this guy’s feet and he took the night stick like it was a bat and he wore the bottom of this guy’s shoes out. I’ve never seen anybody levitate from the ground from a laying position. When he landed on his feet he was running across the street. But I was horrified. I asked my daddy, ‘Why did he do that?’ He looked at me and said, ‘Son, just to let you know, everyone is not treated the same in this world.’ And that was the first litmus test to me that opened my eyes up to realize that something is broken and needs to be fixed.

|

|

| GCR: |

How did the lack of motivation and dire straits of some people you encountered also open up your eyes to troubling situations people were enduring?

|

| AA |

I used to go and talk to individuals to try to fill the voids in my mind. I remember talking to a junkie up top on the roof and I asked him, ‘Why do you shoot this stuff? Don’t you see people dying and turning into zombies?’ He expressed to me this sense that he used to have this girl that he loved so much when he was a youngster and it took him a long time just to talk to her because of the culture. But as time went on he made her his girlfriend. Then they got married and he wanted to be the best father, the best husband ever. Then he said, ‘Do you know what it’s like when you can’t be who you want to be? When you’re supposed to be the breadwinner and you can’t be the breadwinner?’ He said, ‘Then you try to run from yourself. This is why we are who we are. We didn’t anticipate this and being like we are, but we are and it is what it is.’ I got to thinking and there are a lot of guys who had that same story but never had a chance to express it.

|

|

| GCR: |

How did you also expand your thoughts and horizons in a spiritual sense during this same time period?

|

| AA |

I went around looking for religion. I didn’t go looking for religion for the sake of religion. I went there because I felt there had to be a higher power that could fill these voids in my mind. I found a church called Abyssinian Baptist Church. I didn’t know whose church it was, but the first time I went in there I liked what I saw. I told my father, ‘Daddy, I found this church. Why don’t we go as a family?’ My father, my brother and I went. My sister was a baby so she and my mother stayed home. We went to the church and about the third time Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. came out because it was his church. He said, ‘I’m not feeling well today. I’m going to have my son preach the sermon.’ He pointed over to the right and said, ‘There he is over there.’ I said to my daddy, ‘Which one there are three people over there.’ When they said which one, I said, ‘Daddy, it can’t be his son. That’s a white man over there.’ He said to me, ‘He’s not white,’ but I said that he was. My daddy said again, ‘He’s not white. And he’s not passing for white.’ That was the first time I heard the word ‘passing’ relative to race relations. I said, ‘Daddy are you telling me black people are ashamed of being black.’ He said, ‘No, what I am telling you is that some of them pass over and go to the other side not because they are ashamed of who they are, they go to the other side because they want a better standard of life. Imagine that you come out of the house and it is cold and raining, but on the other side of the street the kids have a fruit stand and ice cream, playing jumping jacks and the girls are playing double-dutch – where would you go?’ I said, ‘I would go across the street.’ And my father said, ‘Why son, because you don’t like this side of the street? Why would you go then?’ I answered, ‘Because they’re playing and they have ice cream and all of the goodies.’ ‘Absolutely,’ he said. ‘People don’t go because they are ashamed of who they are. They go because they want a better life.’ If you compare that to today’s activities with aliens coming into the country, they are coming in not because they dislike their home – they just want a better opportunity for them and their families.

|

|

| GCR: |

What was synthesizing in you from the social injustices, thoughts you learned from people who were down and out, church services and what your dad was telling you?

|

| AA |

All of that culminated in my mind. Brought up as a kid, my old man would explain things and then let me come back to him with questions about what I experienced. When I understood what he told me in church, then all of this started adding up in terms of social justice. Then I was thinking, ‘Where are all of the politicians because they play a role? Where is city government because they play a role? Where is the clergy because they play a role?’ I learned right then just like in the movies you see with the cowboys and Indians, that when they kill the Chief the rest of the Indians don’t know what to do. When Malcolm X died, his movement just died with him. When Martin Luther King, Jr. died, his movement died with him. That’s because we don’t have enough people to spread the knowledge so that all are on the same page and we can do what we need to do to make it a better society. We are always looking for that one leader – and I think that’s the wrong way to go.

|

|

| GCR: |

You spoke about that one young man who loved that girl and while your high school peers were focusing on studies or athletics or having teenage fun, you met your wife, Kim, and were married while still in high school. How did this change your life and help you to mature at an early age?

|

| AA |

I felt like I was a man from day one. I was in love with my wife. I just wanted to be the best I possibly could and to give us a decent chance so we got married my senior year in high school. I want to add that my wife wasn’t pregnant at the time. There was no shotgun wedding. I was just in love with her and wanted to get married. My mom wasn’t too happy, but my dad gave us his blessings. He was happy. We went on and we got married and we had a wonderful life until 1968 after Mexico City. Things got real hard on her and for us and she wound up taking her life. I was hurt by her death and am still hurt about it today. My main focus at that time was to secure my kids and to make sure that my kids had a platform to stand on and to understand what happened and why their mom would leave them and leave this world. It was a tough situation and was probably one of the toughest things in my life to have to deal with those circumstances.

|

|

| GCR: |

It was tough also when you made a big life change by going to East Texas State. You ran great and in your one year you set five school records and were a four-time LSC champion, helping the Lions to the 1967 Lone Star Conference title. But there were struggles with racism and with your coach, Delmer Brown. What were the main lessons you learned that year in running and in life?

|

| AA |

It was kind of hard for me when I first got there because they wouldn’t give me a bed there in Texas on a hot day. And there were many, many hot days. Then it was a dry town and I had never heard of a dry town. I found out they didn’t sell any alcoholic beverages there. On the phone with Delmer Brown he always called me by my name, John Carlos. But the minute I got there with my wife and my daughter, the first thing I hear from him is, ‘You boys.’ I told him right there at the airport, ‘My name is John Carlos. You know my name. Don’t call me boy. Don’t disrespect me, my wife and my kid.’ While I saying this I noticed there were signs that said ‘Whites Only’ for the rest rooms and ‘Whites Only’ for the water fountains. Then there were signs for ‘Colored’ and ‘Others.’ That was in Dallas, Texas. That blew me away because I didn’t anticipate Texas being like Alabama or Mississippi or South Carolina. They were just as southern with their attitude. I remember sitting in Delmer Brown’s class – he used to teach anatomy. He used to try to tell the class that black athletes were better athletes because they had extra bones and a tail and this and that. I said, ‘I’ll tell you what coach. I’ll go and get all my money out of the bank and you go get your paycheck. If you can show me there are bones in my body that explain why I’m better than the other athletes on this team I’ll give you my money. But if you can’t, then you give me your money.’ He just laughed that off. This was poison that he was trying to put off on individuals to make them think we were freaks of nature. I can go on about instances in the state of Texas at that time.

|

|

| GCR: |

How much of a positive change was it going the next year to San Jose State and what did you do as far as training and racing in early 1968 since you didn’t have collegiate eligibility?

|

| AA |

We had a program called the Center for a Youth Village and a guy named Woody Lynn was the head coach of the track program. He was like Delmer Brown in that he didn’t know much about coaching, was there for the stipend, and would take us to various meets. At the time I went there, Billy Gaines had just come from New Jersey, Curt Clayton had just moved down from Grambling University and Tommie Smith was finishing up his four years at San Jose State. Also, Jerrod Williams had just come in from Berkeley High School. So we all got together and started running for the Santa Clara Youth Village and formed the relay teams. We also ran in individual races.

|

|

| GCR: |

How did you end up only running one year for San Jose State?

|

| AA |

I wanted to run for the school for the duration of my education, but when I got there I found it was very difficult to run for San Jose State for four years when you had a wife and a kid. I told the coach I admired him for being the guy that he was because Coach Bud Winters was a free-spirited guy like me. I like that. But at the same time I admired the fact that he taught me something that I didn’t know before. He didn’t show me how to run faster as much as he showed me how to run more relaxed. I appreciated that then, and I appreciate it today.

|

|

| GCR: |

How important was it for you and your teammates to contend for the NCAA team championship?

|

| AA |

I sat Coach Winters down and said, ‘Coach, I’m going to run for you for one year and I want to do something for you. Coach, I’m amazed that all of the great runners that you had at San Jose State never won the NCAA championship. For me to pay you back for all you taught me, I’m guaranteeing you right now that we will win this NCAA championship.’ He wanted to know why I would only run on the team for one year and I said, ‘Coach, I can’t feed my family. I can’t do it if I run and go to school.’ So he understood that.

|

|

| GCR: |

Let’s talk about 1969 and first the NCAA Track and Field Championships. You won at 100 and 220 yards and were part of the winning 4 x 110 yard relay and led San Jose State to the team championship. How focused were you for that meet?

|

| AA |

We went to that 1969 nationals in Knoxville, Tennessee and I had already determined that we were going to win this meet. I said, ‘Coach, I’m going to guarantee that I get thirty points for you right off the top.’ We went down to Knoxville and there was talk that I was ineligible. There had been that same talk at the NCAA Indoors as well. The press came to me about whether I was ineligible and I told them, ‘As far as I know, I’m eligible.’ Then I said, ‘Let me be quoted on this – when the races begin, I am here to collect.’ That’s pretty much in a nutshell what happened at the NCAA Championship. We went down there and they did a lot of things to prevent us from winning. But God was on our side and we won anyway.

|

|

| GCR: |

In the 100 yard dash you and Lennox Miller were both timed in 9.2 with six runners within two tenths of a second. What do you recall of your start, where you were mid-race and of the finishing ten yards?

|

| AA |

When I came out of the starting blocks, at that time the shorter guys had the edge coming out of the blocks. My attitude was that if I couldn’t come out first that I had to be in the top three. Now when I came out in the first thirty yards I may have been in about fourth place. By the time we got down the track I was pushing to the front. Then when I hit the stretch there wasn’t anyone who was going to beat me. I don’t know if the race was as close as they tried to make it anyway.

|

|

| GCR: |

In the 4 x 110 relay your team beat both Rice and Texas A and M by four tenths of a second. How tight was it when Ronnie Ray Smith passed the baton to you for the anchor leg and were you flying down the track?

|

| AA |

We ran something like 38.60 in the qualifying heat, but it was raining that day for the final. We were poised to break the World Record that day, but rain showers came through. There were holes in the inside lane barrier to allow the water to seep off the track onto the grassy area. But it rained so hard that the water couldn’t seep through there. So we had puddles of water in lane one. The first time they tried to get us to run there was water all around the track in lane one. So I told the officials they needed to brush the track down and they did. Then the rain came back and we were back in the same situation. Then we ran in the water and rain anyway and we didn’t get the World Record. We were satisfied with what we did do. Curt Clayton led off and Sam Davis ran second. Ronnie ran third and he was a tremendous runner. He gave me the lead and I was of a couple steps ahead. It was just a matter of me bringing it to the tape.

|

|

| GCR: |

As close as the 100 yards was, in the 220 yards you won in 20.2 with places two through seven all at 20.9. Were you just running your race and they were just in another zip code?

|

| AA |

I just went out there to give the people a good show for their money. That’s the attitude I had. It wasn’t about who was in the race or who wasn’t in the race. First of all, my attitude about track and field was so different from most of the track runners. I felt more like a showman than an athlete. I wanted to give the people a good show for their money and I did that many times. I liked to be in the stands talking to the people, drinking a little wine with them, being a little funny with them, talking a little smack with them. When they called me to go run, I would run from the top of the stadium all of the way down. Some of them would say, ‘Oh Carlos, you’re going to be tired by the time you get all of the way down there. What are you going to do?’ I’d look back at them and smile and say, ‘Did you pay your money?’ ‘Yeah, I paid my money!’ Then sit down because I’ve got a package for you!’ If I tied a World Record or broke a World Record, then I’d go back up in the stands with them. That’s probably what’s missing is that we don’t have many showmen other than the guys who want to booty on down the track, but they act like they don’t want to get busy with the people in the stands.

|

|

| GCR: |

It’s interesting when you talk about putting on a show for the fans in the stands. When I ran in high school in Miami at Miami Dade-North Community College there would be seven or eight thousand people in the stands, a full-packed stands from all of the schools, a lot of inner-city schools. They were betting on the races and my senior year I was undefeated in the mile and two-mile. After races I remember talking to people in the stands saying, ‘Hey, did you make any money on me?’ They’d say, ‘No man, no one’s betting against you this year. We can’t make any money on you!’ When you think about that it was like a show – we had Miami Northwestern, Miami Central, Miami Carol City, Miami Jackson, Miami Killian. It was a show and people were betting, there was a lot of excitement and I don’t think high school is like that anymore either.

|

| AA |

I don’t think any level of racing is like that anymore because when they let prize money come into the sport it damaged the sport. Money came in and it wasn’t just that the money was a negative. The negative came when drugs came into the sport following the money. In order for people to get money they decided to take they drugs and be more superior than anybody else. So many individuals started messing with the drugs and chasing that money, that you could sit back and think, ‘Do we have to let the World Record go down to zero seconds for the 100 meters before we do something about this?’

|

|

| GCR: |

John, one more question about that 1969 NCAA Championships – you told Coach Winters you were going to guarantee that win. So was the team championship more exciting than your own individual success?

|

| AA |

I’ve always been a team player. I do my thing in my individual races, but any time we can do something for the team, I will do my part to win my races and then encourage my teammates to do their part. That goes way back to when we pulled off that demonstration. My part was to educate individuals to do their job in terms of what their responsibilities should be. It’s a big deal to swallow to think that you might sacrifice something in your life, but you still had to know the facts that whatever decision you made you had to live with. There are a lot of people fifty years ago who would have a different opinion if it was presented to them today.

|

|

| GCR: |

Were there any other fast or competitive races which stand out in your mind?

|

| AA |

I’ll give you one - in 1969 when I ran 9.1 for the one hundred yards at the Fresno Relays. I beat the field by ten yards. They gave my time as 9.1 and they gave everyone else behind me as 9.3. Now there was a blanket heat behind me with all of those guys. I was so far ahead with 9.1. All of them were so far behind me in 9.3 and I said, ‘How is that possible to be so far in front and to have only two tenths of a second between us?’ Then when I went to the three timers they had me in 8.7, 8.8 and the head timer that was an old man had me in 9.1. He overruled the other watches and said that no one could run that fast. So I went back to one timer and said, ‘Could you explain to me how I can run 9.1 and everyone in back of me ran 9.3 and it’s like a blanket heat behind me?’ The guy shrugged his shoulders and said, ‘Well, I’m not the head timer.’

|

|

| GCR: |

There was another timing problem that was in actuality a ratification issue at the 1968 Olympic Trials when you ran 19.7 for a new World Record at 200 meters. How ridiculous was their disallowance of the record because of your shoes?

|

| AA |

They told me because I had jet-propelled Puma shoes that the record wasn’t allowed. They weren’t hurting me. They were hurting themselves. I went out and set a record and that performance was for the audience. It was an American Record and they chose to take the record away because they didn’t like my politics. That was something they just would have to live with down the line. I just went out to do what I had to do when it was time to do it.

|

|

| GCR: |

How strong and fast were you feeling? Did it really feel like you could tell it was a fast race or were you so relaxed that it wasn’t apparent?

|

| AA |

I knew exactly what I was running. To be honest with you, if I had run in Mexico City like I ran then, I would have been right on schedule. The time I was capable of running was 19.3 or 19.2 – easy.

|

|

| GCR: |

Due to an injury you couldn’t race the first 1968 Olympic Trials 100 meters in Los Angeles and, even though you won the second trial in Lake Tahoe, officials ruled you weren’t eligible for the Olympic team at 100 meters. How disappointing was it that rules and procedures and egos and politics were such a big factor in team selection?

|

| AA |

That was strictly politics. I think there was a conspiracy to keep me out of the one hundred meters so that another individual would be a shoe-in to win the hundred meters.

|

|

| GCR: |

You talked a bit about how strong you ran in 1969 and that year you did win 31 out of 32 races. You won all 14 of your 200m/220y races and 17 of 18 100m/100y races with the only loss when you were second at the AAU 100 yards to Ivory Crockett with both of you timed in 9.3 seconds. What was the story about that one loss in 1969?

|

| AA |

They stole that race from me. When Ivory Crockett won, they just took it from me. It was clear that I had won the race. For some reason one of my cohorts was there and they gave it to the other guy. I think sometimes in my career I had to deal with jealousy and envy as well. That is on those individuals. I don’t get tied up in that stuff. If that’s the way they want to be, it doesn’t take anything away from who I was and what I had to do.

|

|

| GCR: |

The following year of 1970 you did race well winning 11 of 11 100m/100y races and 10 of 10 200m/220y races until injured at AAU 100 yards. Could you tell us about that racing season and also your National Football league tryout?

|

| AA |

I snuggled up to it and realized that I was a detriment to track and field because the guys stopped running to beat me. They raced to see who would be second to me. So I felt that was a detriment. I thought that I’d try another challenge and try to excel in that. Being young, I didn’t know any better and didn’t realize that football was not an industry where you had an opportunity to learn the game. You had to be coming into the game knowing your responsibilities as well as what to do. So it was a bad choice, but the right choice at the same time. My concern was that I could feed my family.

|

|

| GCR: |

During the ensuing years you experienced struggles in your personal and professional life and a lot of it was because of what people perceived about your 1968 statement. How did working with youngsters as a coach and a guidance counselor not just help them and also help you as you progressed through the years on life’s pathway?

|

| AA |

It helped me in that every time I talked to kids and I could see this kid turn his life around in the span I had to work with him it brought enjoyment knowing that I helped save someone’s life and brought them from despair. At the same time I just had a love for kids – period. I tried to educate them as much as I could about things they might have to confront later in life. A funny story is that some kids came to my classroom one day and had a history book. They were arguing back and forth and betting some money about whether this picture was me. There was a picture of the 1968 demonstration. One kid was saying, ‘Mr. Carlos, that’s you isn’t it? Tell them that’s you.’ The other guy said, ‘That’s not him!’ The first guy said, ‘Why wouldn’t it be?’ He looked at me and said, ‘You’re too old to be that guy.’ I said to them, ‘I’ll tell you what fellas. Why don’t you go research it and do research together and come back to ask me about it.’ At the same time, when I look at the History book, it has a picture there, but they didn’t have any explanation of what the picture was about other than three lines under the picture. There was no dialog or history of what or why this demonstration took place.

|

|

| GCR: |

We talked earlier about how people can be so far ahead that others don’t realize what you’re doing until years later. There were many passages and quotes in your book that impacted me and one of my favorites is your statement that ‘You don’t just get in trouble for doing something bad or wrong. You can also get in trouble because you stand up for ideas and principles that challenge people in power. You can earn the anger reserved for those who are so far ahead that people don’t realize what you’re doing until years later.’ Isn’t a great example of this how the statue of your 1968 Olympic gesture was erected at San Jose State decades afterward when people finally realized the importance of what you did and were connected to it?

|

| AA |

Let’s add some clarification. The people who raised the money were the students at San Jose State. It wasn’t the faculty. It wasn’t the administration. It was the student body bringing the finances to make this sculpture. They were saying, ‘Why are you shunning these guys that went to San Jose State? They are our brothers at San Jose State and you act like you are ashamed of them. They had great athletic careers and then went far beyond their athletic careers. Why aren’t they recognized at San Jose State?’ So they chose to raise that money to put that statue there.

|

|

| GCR: |

Can you tell us about how the statue focuses on just Tommie Smith and you while Peter Norman is absent?

|

| AA |

Let me tell you something with regards to Peter Norman. When they were making that statue, I called the guy to see how things were coming along. He said, ‘Tommie’s statue is up and ready and they are working on yours.’ I asked about Peter Norman and they said they weren’t doing anything for Peter Norman. So I got in my car and I drove to San Jose. I went straight to the student body and said, ‘Why isn’t there a statue of Peter Norman being built?’ They told me, ‘Well John, this is for you and Tommie because you went to San Jose State.’ I said, ‘That doesn’t have anything to do with the statement we made – who was from where. This is a team effort. You can’t omit him.’ Then one guy said to me, ‘Mr. Norman didn’t want his statue.’ I was dumbfounded when he said that so I went over to the president’s office and said, ‘Dr. Kaplan, I need to make a long distance call. I need to call Australia.’ I called Peter and he picked up the phone. I explained to him why I was calling and that I had heard he didn’t want his statue put up. ‘Did you step away from us?’ And he laughed. He said this to me which was so profound then and will weigh on my mind for the rest of my life, ‘John, listen. You see, I didn’t do what you and Tommie did. What I did was support what you and Tommie did. I feel it’s only right and only fair that they put the statues of you and Tommie up, and leave my statue blank and void. I’m leaving it void because I want anyone who comes to San Jose State that wants to step in my spot and show their support for what you guys stood for – that’s why I’m not there.’ It was so profound in my mind that Peter said that to God. If there were a billion people, you would be lucky if you found two who would do what he did. God chose him. Another thing is that all three of us on the victory stand are born in the sign of Gemini and very close in time. I’m June 5th, 1945. Tommie Smith is June 6th, 1944 and Peter is June 15th, 1943. So God chose Geminis, who are supposed to have division, to carry out this mission.

|

|

| GCR: |

In recent years you have been honored with induction into the USA Track and Field Hall of Fame in 2003, National Consortium for Academics and Sports HOF in 2010 with Dr. Lapchick which is right here in the Orlando area where I live, Texas A and M-Commerce (East Texas State) HOF in 2012, San Jose Sports HOF in 2015 along with other honors such as the Arthur Ashe Award for Courage at the 2008 ESPY Awards. Are these honors both gratifying and humbling?

|

| AA |

What awards are to me are people applauding your efforts in life. I don’t make my efforts in life for applause. I make my efforts in life to make connections with that one individual. I could have a thousand people in the audience and I’m communicating to each one. I have to focus to make sure I reach that one. When they go to applaud, I tell them I don’t want applause. If they feel like they must do something, then put a little jingle up on the stage (laughing). Awards to me are something that I attribute to back then. I don’t want material goods as must as I want people to recognize that I have a vision and am fighting for my vision. And I want people to realize that they have an opportunity to have a vision and to fight for that vision as well.

|

|

| GCR: |

How is your current health and what do you do for fitness?

|

| AA |

The biggest problem I have now is having the time. I haven’t been able to do too much exercising because I had a knee replaced and the one they gave me isn’t one of the best. I can’t go out and do any running or jogging. I’m going to start going to the gym and doing some water aquatics. It’s the time factor because I’m moving so fast and flying all over the country so I just don’t have the time to go to the gym like I need to. I’m trying to do what I can to get fit and to keep up my physical appearance. I don’t want to end up trying to bend over to where I can’t see my shoes.

|

|

| GCR: |

What are some of your goals for the future in terms of personal development, continuing to help others, setting an example, travel and do you see yourself slowing down or doing as much as you can?

|

| AA |

There is no slowing down. I think I’ve come to the conclusion in life that this is what I was born for on this planet. God chose me to do this and I’ll do this until it’s over. I grew up in New York under the mantra of ‘Each one, teach one.’ If I can give a lesson to you, it’s no good if you shield that lesson for yourself. You take that lesson I give you and then teach somebody else that same lesson.

|

|

| GCR: |

In line with that thought, what advice do you give to youth and teenagers so that they can be their best and reach their potential as human beings with the gifts they have been given that all comes together in the ‘John Carlos philosophy?’

|

| AA |

The first thing you need to do is to get in touch with the man in the mirror. Know who you are. Know your strengths and your weaknesses. Know what you lack and know what you don’t lack. Know where you want to go but where you are. You can’t help anyone until you help yourself. You have to make sure you have a solid foundation. Then you can go out and help anyone in the world. There are two types of foods – if I stop eating then I’m going to die. Then there is another type of food of nourishment and that is the food of education. So I ask, ‘What happens if you don’t get that type of food?’ And kids will say, ‘I don’t know Mr. Carlos.’ I tell them, ‘If you don’t get the food of knowledge, you will wish you were dead. Now figure that one out.’ If you eat you will live. If you don’t eat you will die. If you don’t get education you will wish you were dead because life is going to be so bad for you because you have nothing to offer society. That’s what I tell kids – make sure you get nourishment on both sides, physical and mental.

|

|

| GCR: |

Now when people think of John Carlos and after you are gone when people think of John Carlos, what do you want them to think of in terms of your legacy or what you have done for humanity?

|

| AA |

A man asked me, ‘What do you want on your tombstone?’ I said, ‘Here lays a man.’ That’s all. All of us are given gifts which is very true. But do you know what the gift of life is? It’s that we are being pushed into the game as this is a game that we are in. The difference is this – in a game like basketball, football, baseball, hockey or soccer – we are trying to be a part of that game and a part of that team. In those games we are applying to be in there. But in the real game there is no applying. We are pushed in there. What is the concept of those games compared to the game I just mentioned? To win! That is absolutely right! But how are we going to win the game if we don’t even know we are in the game? And here a large percentage of people in society don’t even realize they are in the game. Out of that ten percent that do know they are in the game, half of them don’t even realize there are rules in the game. People need to start looking at life from that perspective – you are in this game to win. When there is an orchestrated way like a tug-of-war in a sand pit they can put thirty guys on one side and thirty guys on the other side. On one side there are thirty strong guys while on the other side they are not as strong. But then when the tug-of-war goes, just the fact that you have the courage to stand up, against the ‘one percenters,’ so to speak, so that they can’t pull you into the slop in the middle gives you something. What that does is it gives people who are watching as they are going by encouragement to help these individuals. When we look back in retrospect at 1968, I was a gardener and did horticulture. I tilled the earth, I planted seeds, I watered them and I have a tree. It’s a fruit tree of humanity. You’ve never seen a fruit tree deliver only one piece of fruit. So when we think back now about that tug-of-war and that fruit tree and people may ask me about what I did fifty years ago and whether I accomplished anything. I am able to say I accomplished something because they are still talking with me about it. Here we are fifty years later and what you see on that tree is the fruit of my labor. It’s the young individuals in the NFL. It’s the young individuals in the arts. It’s the young teachers in the schools. There are a lot of people that have my mindset.

|

|

| GCR: |

Finally, John, if someone would like to order your book, ‘The John Carlos Story,’ what should they do?

|

| AA |

If anyone would like to order my book, they can send a check for twenty-five dollars to me at P.O. Box 1237, 1333 Ceder Creek Lane, Conley, GA 30288. They can indicate the name they would like the book autographed to and they will receive an autographed copy of ‘The John Carlos Story.’

|

|

| |

Inside Stuff |

| Hobbies/Interests |

My first interest is in my family. I’m not just talking about my immediate family, but also my cousins and nieces and nephews and distant cousins. I just have a strong vibe for the Carlos family

|

| Nicknames |

When I was a little boy they used to call me ‘Dirty Red.’ I used to have red hair when I was a kid. As I got involved in track and Field they called me ‘The Gypsy.’ They would say I was a wanderer. Then when I got a little older they started calling me ‘The ‘Los’ which was short for Carlos

|

| Favorite movies |

It’s called ‘Stand by the Door.’ It’s from the 1960s

|

| Favorite TV shows |

When In was a youngster the show I liked to watch was ‘Rin Tin Tin’ about the dog - the German Shepherd. In modern day I like wildlife shows because I think animals are a very strong educational tool for the human species

|

| Favorite music |

I’m into jazz so there are a whole bunch of musicians. I’ll go with Johnny Marple, John Coltrane, and Miles Davis. If I’m to pick someone with vocals, in my estimation the greatest singer was Nat King Cole

|

| Favorite books |

There are so many that I don’t know if I have a favorite as much as just trying to keep up with people’s thought processes and how they view society. I can’t really put my finger on one book that I can say is more valuable than the others

|

| First cars |